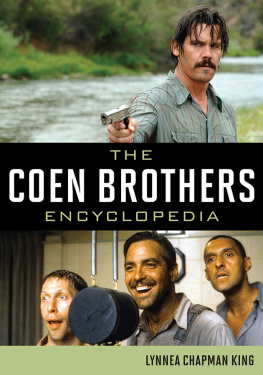

C inematographer, friend and part-time interpreter of the Coen mystery, Barry Sonnenfeld tells a story about the family dog. This ancient dog was in a sorry state, having lost most of the mobility in its hind legs. So it was sort of dragging itself around the house, laughed Sonnenfeld, urinating everywhere. Finally, one Saturday morning, it was decided the brothers must take the dog to the vet to be put out of its misery. As Joel started the car, Ethan stooped to pick up the lame mutt. Whereupon the dog miraculously sprang up on its legs and ran for its life, straight into the road, where it was struck by a passing car and killed.

I hope it is true, concluded Sonnenfeld, because it would explain so much about their sense of humour

I have interviewed the Coen brothers, or attempted to, on four occasions. They were unfailingly polite, but evidently pained by the experience. Its nothing personal. Famous actors have been faced with the same stony faces and Cheshire-Cat grins, the same insane laugh.

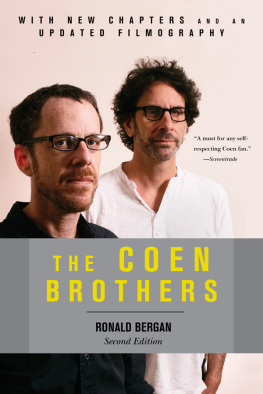

Joel Coen and Ethan Coen discuss their film Inside Llewyn Davis in New York in 2013.

What strikes you is how unalike they are. Doubtlessly, that shouldnt come as a shock. There are three years between them. Joel is taller, with dark hair that once sprawled down his shoulders, but with age has retreated to a more formal thatch. Ethan is shorter, with wiry, ginger hair. His voice (and laugh) is higher in register. Yet the way they make films is so supernaturally connected, it is hard not to think of them as twins.

They cant help but to talk to one another, finish the others sentences, go off at wild tangents, embark on awkward silences, scratch their heads and break into discordant gusts of herky-jerky laughter.

Every time we met, Joel looked like a thunderstorm, but tended to be more open. Ethan giggled like a schoolboy, as if the idea someone might ask him questions came as a shock. He has a habit of pacing the room in slow circles like a cat. When I caught up with them for their soon-to-be Oscar winning neo-Western No Country for Old Men, he disappeared entirely into the bathroom. Joel barely raised an eyebrow on the sofa from which he never stirred.

They never profess to remember me. Though the last time to dance around Inside Llewyn Davis Joel peered at me suspiciously as if I had once tried to sell him something.

They cant help but to talk to one another, finish the others sentences, go off at wild tangents, embark on awkward silences, scratch their heads and break into discordant gusts of herky-jerky laughter. They claim to wince when they read themselves in print. They once spotted that a brazen journalist had made up all their quotes for them. Best interview we have ever given, smirked Ethan.

People love to describe them as quirky, or plain weird, but theirs is a mission to maintain their own temperature of normality. They come knowingly underdressed in jeans and sneakers. There is simply no ego present; they are anathema to Hollywoods gaudy principals.

Thats the great thing about Joel and Ethan, confirmed Sonnenfeld. They dont wanna be on the Today show. They dont want to be in People. They dont give a shit. They wanna have a good time.

As will become evident over the coming pages, their cleverness is unquestionable. Yet they are incapable of engaging with their films, or lives, on anything more than a cursory level. Why they do what they do isnt a consideration. Its just what they do. The best intentioned of journalists will be met with an awkward staccato of Its only a film, We just dont think that way and Drawing a blank on that one.

Yet their films possess so much hidden meaning and potential symbolism and are made with such a personal signature.

Such is the Coens non-participation in the Coen game, you wonder if long ago, over cigarettes and coffee in the corner of some Dennys, they swore a blood pact never to come clean.

To be fair, Joel and Ethan are willing to be drawn on the processes of filmmaking itself: the craft, influences and collaborators. But they own up to making choices by no greater reasoning than, We liked the idea, It made us laugh or It felt right. They treat every enquiry, no matter how flattering or elaborate, with a staunch matter-of-factness. Why is Fargo called Fargo? Its a better name than Brainerd.

Just dont ask them about the grand themes, In other words, its in their Minnesotan blood.

The films themselves even send up the idea of enquiry and puncture pomposity: how Larry Gopnik strives for answers from a heedless God in A Serious Man, or Barton Fink wrestles with his art. Whatever the case, they are never going to crack and I wouldnt have them any other way.

Their films are beautiful, dark and funny, and profound in ways that is hard to classify. They are full of contradictions, being deeply referential, but wholly original; highly personal, yet built from artifice; filled to the brim with high and low culture. This is the dream known as Coenesque.

Consciously or otherwise, there is connective tissue between their experiences and the stories they instinctually tell. It might be easy to observe Coencharacteristics in Barton Fink, or Larry Gopnik or even Marge Gunderson. But you cant help but feel there is a Coenness in all of their characters.

Their universe is all about people trying to find a code of conduct in a universe of madness,ing films, their subject is the human condition. Whatever that is.

Once asked what his philosophy of filmmaking might be, Princeton philosophy graduate Ethan Coen winced. Oooh I dont have one, he dithered, I wouldnt even know how to begin. Youve stumped me there. None that Ive noticed. Drawing a blank on this one.

SALAD DAYS

Growing up in Minnesota

In the winter, Minnesota can get so cold your eyeballs freeze. During the dog days of summer, it becomes hot and listless, and the sky goes on forever. Think of Fargo and A Serious Man, take away the guileless crime and existential roughhousing, and youre left with a picture of the seasonal variations of the Coens formative years. Whatever the time of year, the landscape remains pancake-flat, the roads disappearing into nothing. Given such a vista, the immigrant mix of Protestant German and Scandinavian stock, as well as pockets of Russian Jews, developed the marmalade slow vowels and emotionally impassive temperament classified as Minnesota Nice.

S t. Louis Park, the Midwestern suburb of Minneapolis which the Coens called home, was a dreary place to grow up. The mythical lumberjack Paul Bunyan was reputed to have been born in nearby Brainerd, while the genuine folk troubadour Bob Dylan was bred in Duluth and raised in Hibbing. That was it as far as local celebrity. The brothers have confessed that all the outrageous crimes perpetrated in the name of good storytelling across their far-flung films were partly a reaction to the monotony of their upbringing their own little industry of Minnesota Nasty.