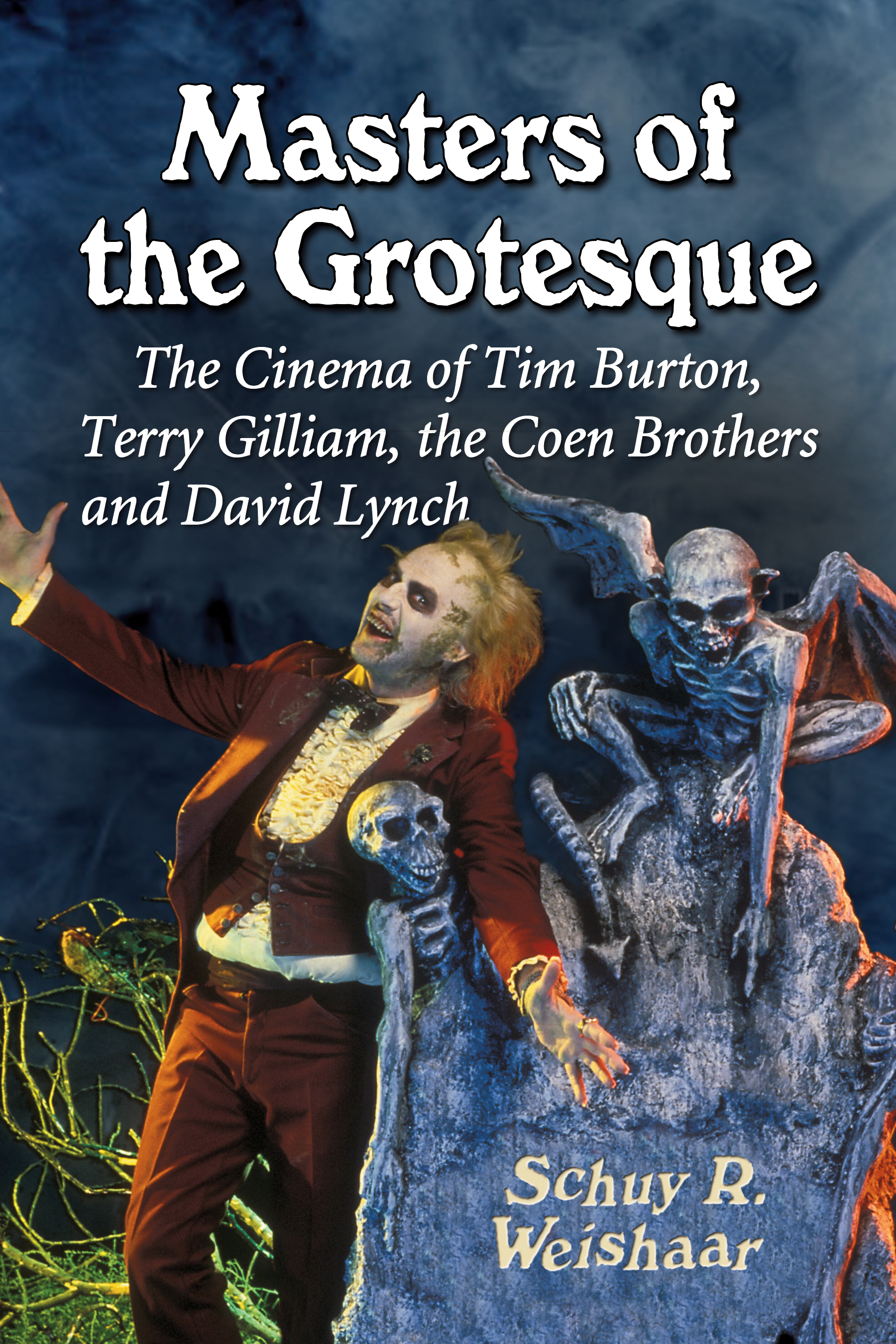

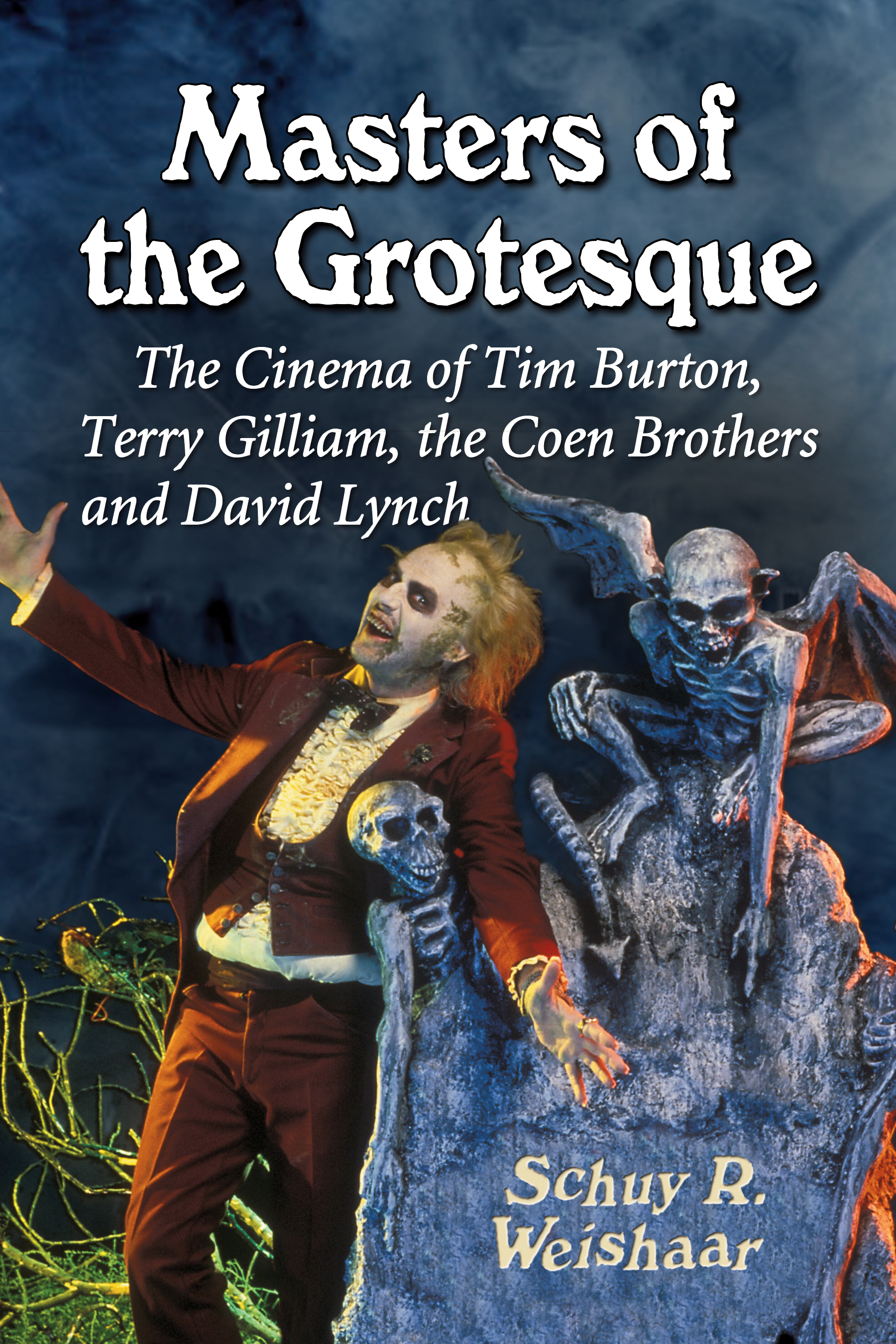

Masters of the GROTESQUE

The Cinema of Tim Burton, Terry Gilliam, the Coen Brothers and David Lynch

SCHUY R. WEISHAAR

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-0060-4

2012 Schuy R. Weishaar. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover image: Michael Keaton in Beetlejuice, 1988 (Warner Bros./Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Felicia, Finn, Athan, and Kyle

It is something to have been

Acknowledgments

My interest in the grotesque began when, as an undergraduate, I had the good fortune to discover the works of Sherwood Anderson, William Faulkner, Flannery OConnor, Tom Waits, Johnny Dowd, Nick Cave, Pieter Bruegel, Hieronymus Bosch, and surrealism at approximately the same time. (It was a good year.) This interest has been fostered by professors, friends, and colleagues in courses and conversations that haven taken place at and around Trevecca Nazarene University, Duke University, and Middle Tennessee State University: thanks to Rob Blann, Annie Stevens, Steve Hoskins, Holly and Boyd Taylor Coolman, Kevin Donovan, Carson Walden, Brannon Hancock, JJ Ward, Billy Daniel, Syndi and Mark Woods, Brandon Arbuckle, Jooly Philip, Graham Hillard, and Nate Kerr for their guidance, friendship, and support. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Linda Badley and Allen Hibbard for reading and providing helpful criticisms for an early draft of this work, as well as to David Lavery, under whose direction this work began.

Finally, special thanks to Mallory Carden for her attentiveness in finding my mistakes; to Kyle Weishaar for his mad genius and his music (Manzanita Bones); and, most of all, to my wife Felicia for her love, support, sanity, and brilliance.

Preface

I would like my pictures to look as if a human being had passed between them, like a snail, leaving a trail of the human presence and memory of the past events as the snail leaves its slime.

Francis Bacon, Francis Bacon: Painter of a Dark Vision

Here is lots of new blue goo now. New goo. Blue goo. Gooey. Gooey. Blue goo. New goo. Gluey. Gluey.

Dr. Seuss, Fox in Socks

The grotesque is often conceived of as an aesthetic dimension divided in two, one side gravitating towards the dark, terrifying, and macabre, the other towards the bright, jovial, and ridiculous. These contrastive poles share certain elements of style, structure, pattern, form, etc.all of the factors upon which the continuum of the grotesque itself is predicatedbut, even while there may be minimal interplay between them (so continues this strain in the theory), most grotesquery in art gravitates towards the one side or the other. There is a kind of obviousness to this claim. When we look upon the paintings of Pieter Bruegel the Elder or Hieronymus Bosch, we probably perceive both as grotesque. But (as someone once explained to me during my college days) while Bruegel seems to dabble in the dark and horrifying, we may observe that the light and somewhat ridiculous seem more representative of his true vision, and while certain Bosch works retain an air of silliness, what we are arrested by are his obscenely grim triptychs.

But what happens when we pay slightly closer attention, or a different kind of attention, or when we multiply our critical perspective? What happens when we interpret the two painters from within the space of their contradiction? Do we not identify as much of the ludicrous in Bosch as in Bruegel and as much of the terrible in Bruegel as in Bosch? It is the contention of the present study that when we deal with the grotesque, we are faced with a multifaceted, polyvalent corpus of theories, traditions, content (subject matter, etc.), images, themes, motifs, formal/structural apparatuses and patterns, and so forth, which problematize the notion of convenient conceptual bifurcations such as light and dark, good and evil, sacred and profane, beautiful and ugly, etc. Rather, it is my contention that, insofar as we approach the grotesque in something or insofar as we approach something with the grotesque, we must perceive these sides or poles of our evaluative or critical distinctions in new light, as, in a way, inverted twins of one another, as identical opposites. If this is the case, then to thoroughly explore the grotesque one must spiral towards the inward space of contradiction, of paradox, towards the midzones between identical opposites, before spiraling back out, as it were, into evaluations: this is grotesque par excellence.

We can perceive the aperture of such spaces in the world represented in the paintings of Francis Bacon, perhaps even more immediately and explicitly than in those of Bruegel and Bosch. The Baconian world is full of these tensions between any of a number of related binaries, perhaps most prominently dramatized in the repeated motif of his oozing, pearlescent, fleshily indistinct figures (Are they developing, becoming, or are they rotting, dying? Are they stuck in the middle? Are they coming apart, even as they are becoming?) trapped within a demarcated area, an interior non-place (Domino 70). These areas or non-places are angular constructions that resemble abstract cages, chairs, and pedestals, or, more frequently, they are simply furnished, lushly painted otherwise vacant rooms. The paintings image a vague, interior space, the abortive/developing flesh-figure, spilling or smearing out from itself, residing there in the room, perched aloft the toilet or chair, sprawled out across the bed or rug, or oozing from a square on the wall down onto a table. These are troubling spaces to be sure, spaces rife with the potential for the grotesque. One critic has written that the darker, more disturbing use of the grotesque is critical in Bacons work, functioning as a means of pushing us beneath the surface of reality to a deeper dimension, one concerned essentially with the reality of despair (Yates, Francis Bacon 163, 161).

But, if we can perceive this despairing grotesque opening out from within the space of the Baconian worldif we can feel it heremust we not also admit that we can feel its inverted twin yawning within the preposterous world of Dr. Seuss? The Seussian world is populated with grotesque evolutionary degenerates and malformed, human-like (in one way or another) fusions of beast and bird and reptile, etc., who are set adrift in a meaningless, menacing world, which seems itself to be alive, one which seems to be pieced together in a flimsy architecture of knobby, furred joints and cavities, walkways, train tracks, and habitations perched rather precariously on its elbow-like bumps and knee-like bends or baroquely structured in, around, or upon its orifices and protuberances. The Seussian world surely dwarfs the medieval bestiaries and devilries in the sheer variety of its creatures; it surely outstrips the worlds of Bruegel or Bosch in its portrayal and enumeration of human vice. In some ways, we may even perceive the Seussian world as more subversively grotesque than Bacons, for while both image the humanlike figure as some mimetic maceration of the original upon which it is based in some other, alienated, contradictory space, Seuss more thoroughly distorts and alienates this world itself as well. In general, there are none of the banal comforts offered to Bacons smeared subjects in lieu of their missing meaningno bourgeois domestic accoutrements or possessions: no plush couches, no toilets, no (proportionally adequate) bedsno place to sit or shit or screw (all behaviors that Bacons figures engage in). Seusss protagonists have no time for bourgeois trivialities or pleasures. They are constantly on the run, careening through a world which looks like it could fall apart at any moment or swallow them whole or brush them away, a world of absurdity and despair, one in which they have been given a role in some ludicrous game that they do not understandand that game is their life. And more radical still: the protagonists in the Seussian world still (sometimes grouchily) hope, without whining; they hope, not for meaning per se, but for justice, peace, and community.

Next page