PENGUIN  CLASSICS

CLASSICS

FRANKENSTEIN

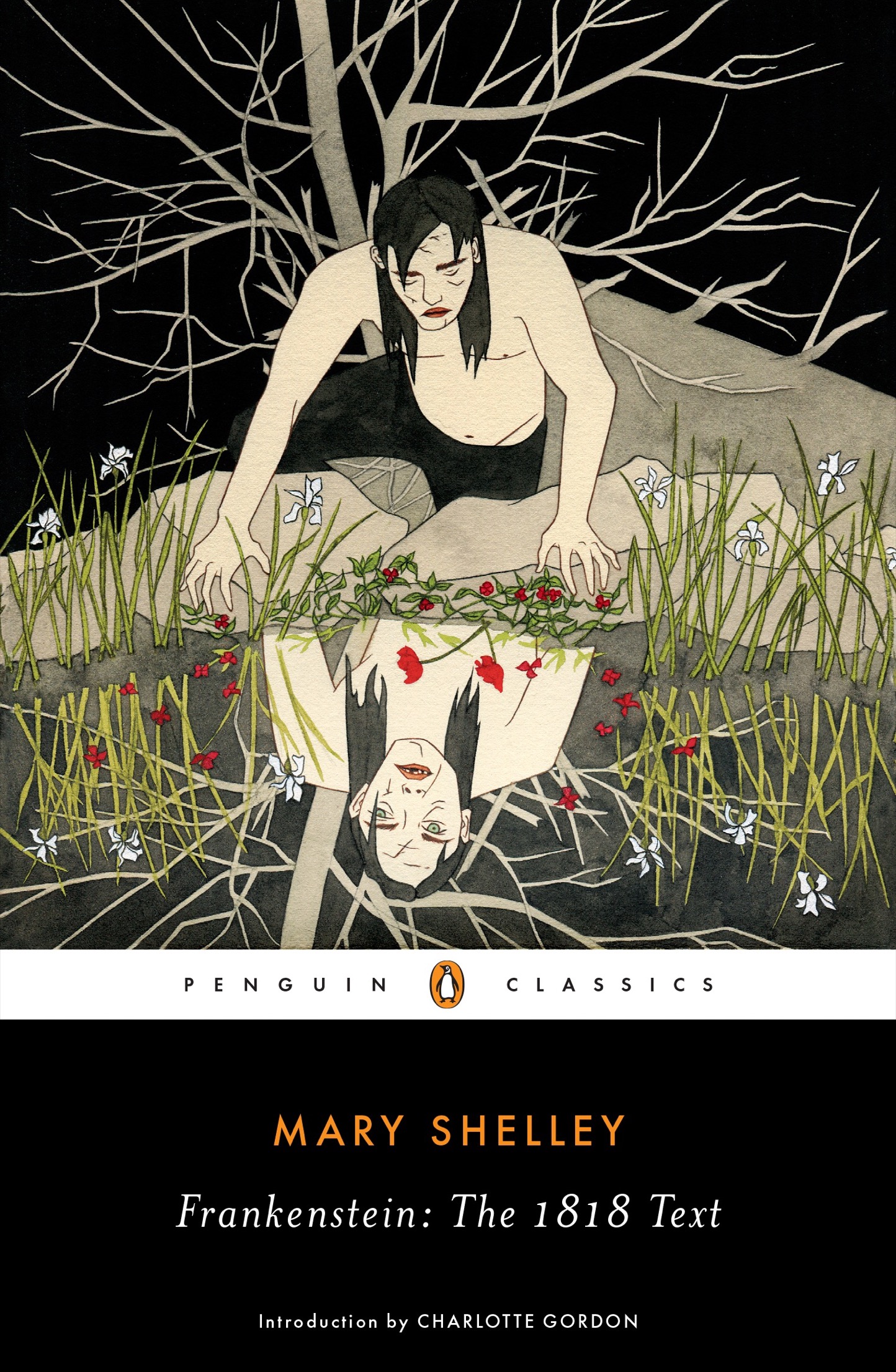

THE 1818 TEXT

MARY SHEL LEY was born in London in 1797, daughter of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, famous radical writers of the day. Marys mother died tragically ten days after the birth. Under Godwins conscientious and expert tuition, Marys was an intellectually stimulating childhood, though she often felt misunderstood by her stepmother and neglected by her father. In 1814 she met and soon fell in love with the then unknown Percy Bysshe Shelley, and in July they eloped to the Continent. In December 1816, after Shelleys first wife, Harriet, committed suicide, Mary and Percy married. Of the four children she bore Shelley, only Percy Florence survived. They lived in Italy from 1818 until 1822, when Shelley drowned following the sinking of his boat Ariel in a storm. Mary returned with Percy Florence to London, where she continued to live as a professional writer until her death in 1851.

The idea for Frankenstein came to Mary Godwin during a summer sojourn in 1816 with Percy Shelley on the shores of Lake Geneva, where Lord Byron was also staying. She was inspired to begin her unique tale after Byron suggested a ghost story competition. Byron himself produced A Fragment, which later inspired his physician John Polidori to write The Vampyre. Mary completed her short story back in England, and it was published as Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus in 1818. Among her other novels are The Last Man (1926), a dystopian story set in the twenty-first century, The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (1830), Lodore (1835), and Falkner (1837). As well as contributing many stories and essays to publications such as the Keepsake and the Westminster Review, she wrote numerous biographical essays for Lardners Cabinet Cyclopaedia (1835, 183839). Her other books include the first collected edition of Percy Bysshe Shelleys Poetical Works (4 vols., 1839) and a book based on the Continental travels she undertook with her son Percy Florence and his friends, Rambles in Germany and Italy (1844). Mary Shelley died in London on February 1, 1851.

CHARLOTTE GORDON is an award-winning author whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Slate, and Washington Post, among other publications. Her latest book, Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley (2015), won the National Book Critics Circle Award. She has also published Mistress Bradstreet:The Untold Life of Americas First Poet (2005) and The Woman Who Named God: Abrahams Dilemma and the Birth of Three Faiths (2009). She is a Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at Endicott College.

CHARLE S E. ROBINSON was a professor of English at the University of Delaware, frequently lectured on The Ten Texts of Frankenstein, and edited Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus: The Original Two-Volume Novel of 18161817from the Bodleian Library Manuscripts, by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley(with Percy Bysshe Shelley) (2008), reprinted in paperback by Vintage Books (2009). His other books included Shelley and Byron: The Snake and Eagle Wreathed in Fight (1976); an edition of Mary Shelley: Collected Tales and Short Stories, with Original Engravings (1976); The Mary Shelley Reader (1990), coedited with Betty T. Bennett; an edition of Mary Shelleys Mythological Dramas: Proserpine and Midas (1992); and the two-volume Frankenstein Notebooks (1996).

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

First published in Great Britain 1818

This edition with an introduction by Charlotte Gordon published in Penguin Books 2018

Introduction copyright 2018 by Charlotte Gordon

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Chronology, How to Read Frankenstein, and Suggested Further Reading by Charles E. Robinson first appeared in slightly different form in Frankenstein, Penguin Enriched eBook Classic. Copyright 2008 by Charles E. Robinson.

Ebook ISBN: 9781524705701

Cover illustration: Marci Washington

Version_1

Contents

Introduction

When Frankenstein was first published in 1818, many readers were shocked. What could be more appalling than the tale of a mad scientist creating life? What kind of person would write such a terrible story? Critics believed the novel was hostile to religion, as it depicted a human being attempting to appropriate the role of God. One contemporary writer complained that the book was horrible and disgusting. He declared that the author must be as mad as his hero. He could not accuse anyone in particular, however, as no one knew the authors identity. The book had been published anonymously, and when people discovered the authors name, the truth seemed even more scandalous than the horrible story itself. The author was a woman, and her name was Mary Godwin Shelley.

In the nineteenth century women werent supposed to write novels, let alone a novel like Frankenstein. Middle-class women were expected to confine themselves to being good wives, daughters, and mothers. For a woman to step outside of her proper domain was against all of societys rules. Critics muttered that Mary Shelley must be as monstrous and immoral as her story. And yet when they met her, they were surprised to find that Mary was ladylike and reserved. One new acquaintance said that he had thought the author of Frankenstein would be indiscreet and even extravagant, but that he had found her cool, quiet, feminine. It was difficult for Marys contemporaries to square the boldness of her work with its creator. Instead of being improper or masculine, she appeared to embody their ideas of what womanhood should be.

Sadly, these misogynistic principles were the accepted ideas of the time. Experts declared that women were inferior to men in all areas of human development and could not be educated beyond a certain rudimentary level. Whereas men possessed the capacity for reason and ethical rectitude, women were considered foolish, fickle, selfish, gullible, sly, untrustworthy, and childish. Wives could not own property or initiate divorces. Children were the fathers property. Not only was it legal for a husband to beat his wife, but men were encouraged to punish any woman they regarded as unruly. If a woman tried to escape from a cruel or violent husband, she was considered an outlaw, and her husband had the legal right to imprison her.

This oppressive system began in childhood. Boys were taught that they were superior to girls. Girls were instructed to submit to their brothers, fathers, and husbands. The education of middle- and upper-class young women was confined to activities such as playing the piano, speaking French, embroidering, and singingdecorative skills that would help them appear attractive to prospective husbands, but would not teach them to think for themselves. Any serious scholarship was strongly discouraged, as too much study seemed like a dangerous proposition, not so much for the world but for women themselves. Were their constitutions strong enough for such exertion? Should they learn more than basic skills, such as how to write their names, add and subtract, and read simple passages? Most people thought the answer was no; given their fragility, women should not be taxed too much. Besides, too much book learning could destroy a womans life and ruin her prospects for marriage. If you happen to have any learning, keep it a profound secret, warned one father.

CLASSICS

CLASSICS