All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Published in the United Kingdom by Hutchinson, a member of The Random House Group, London.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

London, England, on August 30, 1797, a newborn baby fought for her life. Small and weak, she was not expected to survive. Her mother struggled to deliver the afterbirth, but she was so exhausted a doctor was called in to help. He cut away the placenta but had not washed his hands, unwittingly introducing the germs of one of the most dangerous diseases of the erachildbed or puerperal fever. Ten days later, the mother died, and, to the surprise of everyone, the baby lived. For the rest of her life, she would mourn her mothers loss, dedicating herself to the preservation of her mothers legacy and blaming herself for her death.

London, England, on August 30, 1797, a newborn baby fought for her life. Small and weak, she was not expected to survive. Her mother struggled to deliver the afterbirth, but she was so exhausted a doctor was called in to help. He cut away the placenta but had not washed his hands, unwittingly introducing the germs of one of the most dangerous diseases of the erachildbed or puerperal fever. Ten days later, the mother died, and, to the surprise of everyone, the baby lived. For the rest of her life, she would mourn her mothers loss, dedicating herself to the preservation of her mothers legacy and blaming herself for her death.

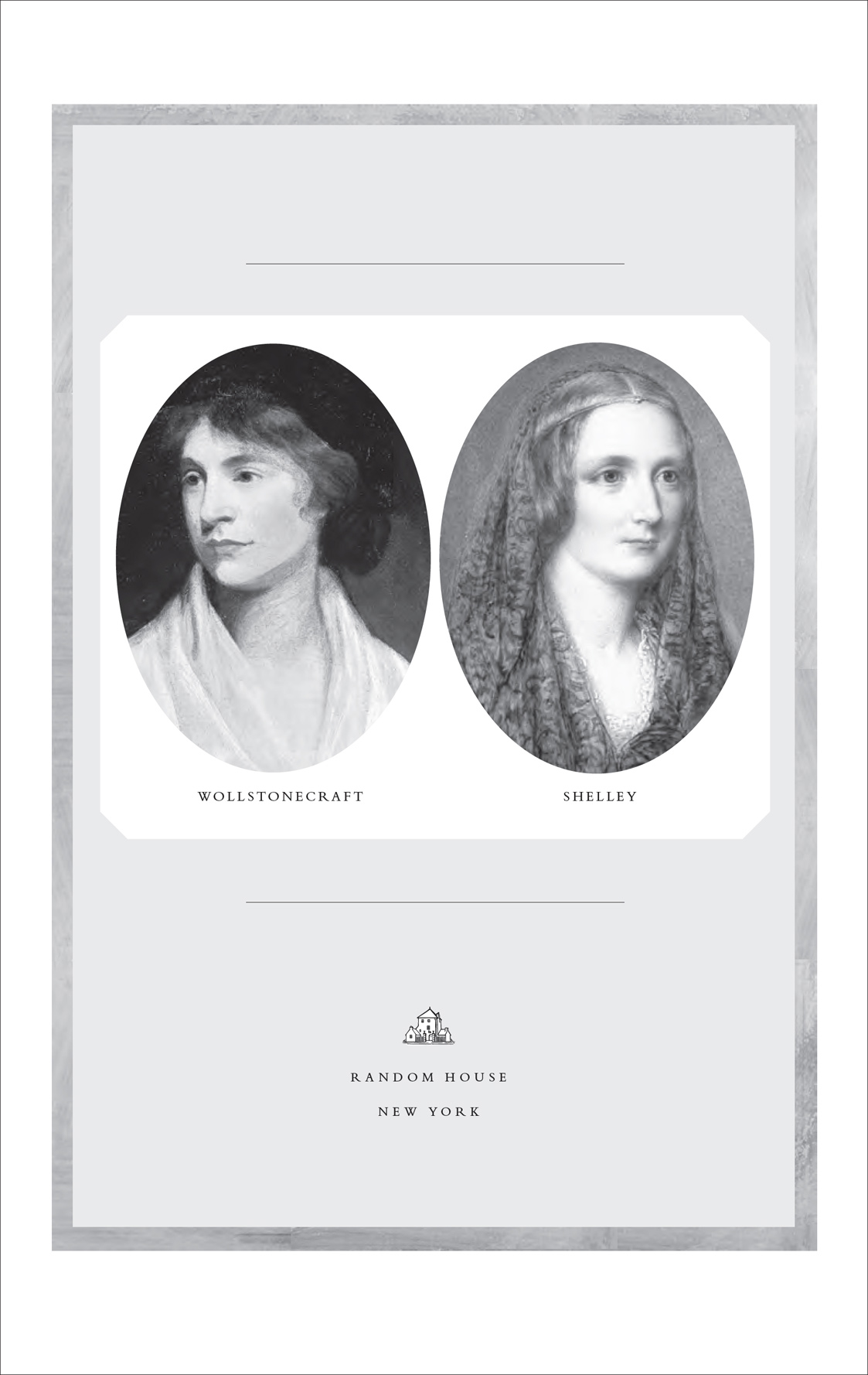

This is one of the most famous birth stories in literary history. The dead womans name was Mary Wollstonecraft. Five years earlier, Wollstonecraft had scandalized the public by publishing A Vindication of the Rights of Womana denunciation of the unfair laws and prejudices that restricted eighteenth-century womens lives. The daughter she left behind would become the legendary Mary Shelley, the nineteen-year-old author of Frankenstein, a novel so famous it needs no introduction.

Yet even those who are familiar with Wollstonecraft and Shelley are still sometimes startled to learn they were mother and daughter. For generations, Wollstonecrafts premature death led many scholars to overlook her impact on Shelley; they viewed mother and daughter as unrelated figures representing different philosophical stances and literary movements. Shelley appears in the epilogues of biographies of Wollstonecraft, and Wollstonecraft in the introductory pages of lives of Shelley.

Romantic Outlaws is the first full-length exploration of both womens lives. But long overdue though it is, this book is deeply indebted to the work of earlier scholars. Without their efforts, it would have been impossible to explore Wollstonecrafts contributions to Shelleys life and work, or Shelleys obsession with her mother.

This might sound like an odd proposition. How could a mother who died ten days after she gave birth have had such an inordinate impact on her daughter? But strange though it may seem, Wollstonecrafts influence on her daughter was profound. Her radical philosophy shaped Shelley, sparking her determination to be someone and to create a masterpiece in her own right. Throughout her life, Shelley read and reread her mothers books, often learning their words by heart. A large portrait of Wollstonecraft hung on the wall of Mary Shelleys childhood home. The girl studied it, comparing herself to her mother and hoping to find similarities. Mary Shelleys father and his friends held up Wollstonecraft as a paragon of virtue and love, praising her genius, bravery, intelligence, and originality.

Steeped as she was in her mothers ideas, and raised by a father who never got over his loss, Mary Shelley yearned to live according to her mothers principles, to fulfill her mothers aspirations, and to reclaim Wollstonecraft from the shadows of history, becoming, if not Wollstonecraft herself, then her ideal daughter. Over and over again, she reimagined the past and recast the future in a doomed effort to resurrect the dead, gazing back at what she could never regain but sought to duplicate in very different times.

As for Wollstonecraft, though she shared only ten days with her child, she was profoundly influenced by the idea of children. She had directed most of her lifes work toward the next generation, dreaming of what life might be like for them and how she could help them inherit a more just world. Wollstonecrafts earliest works, written before her famous Vindication, were education manuals, books about how to teach children, and what to teach children, especially daughters. Condemned by her own era, she turned to those who would come after, drawing inspiration from those who might read her books once she was dead, never once dreaming that one of her most important readers would turn out to be the daughter she left behind.

Romantic Outlaws alternates between the lives of Wollstonecraft and Shelley, allowing readers to hear the echo of Wollstonecraft in Shelleys letters, journals, and novels, and demonstrating how often Wollstonecraft addressed herself to the future, to the daughter she planned to raise. There are many comprehensive biographies of both women, written by some of the most distinguished literary scholars of the preceding generations, but Romantic Outlaws sheds new light on both Wollstonecraft and Shelley by exploring the intersections between their lives. And the intersections are many.