Contents

Guide

William Godwin

Also available:

Salvador Allende

Revolutionary Democrat

Victor Figueroa Clark

Hugo Chvez

Socialist for the Twenty-first Century

Mike Gonzalez

W.E.B. Du Bois

Revolutionary Across the Color Line

Bill V. Mullen

Frantz Fanon

Philosopher of the Barricades

Peter Hudis

Mohandas Gandhi

Experiments in Civil Disobedience

Talat Ahmed

Leila Khaled

Icon of Palestinian Liberation

Sarah Irving

Jean Paul Marat

Tribune of the French Revolution

Clifford D. Conner

John Maclean

Hero of Red Clydeside

Henry Bell

Sylvia Pankhurst

Suffragette, Socialist and Scourge of Empire

Katherine Connelly

Paul Robeson

A Revolutionary Life

Gerald Horne

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Poet and Revolutionary

Jacqueline Mulhallen

Toussaint Louverture

A Black Jacobin in the Age of Revolutions

Charles Forsdick and Christian Hgsbjerg

Ellen Wilkinson

From Red Suffragist to Government Minister

Paula Bartley

Gerrard Winstanley

The Diggers Life and Legacy

John Gurney

William Godwin

A Political Life

Richard Gough Thomas

First published 2019 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright Richard Gough Thomas 2019

The right of Richard Gough Thomas to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 3836 1 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 3835 4 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 7868 0389 4 PDF eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0391 7 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0390 0 EPUB eBook

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England

Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America

Contents

Series Preface

Revolutionary Lives is a series of short, critical biographies of radical figures from throughout history. The books are sympathetic but not sycophantic, and the intention is to present a balanced and, where necessary, critical evaluation of the individuals place in their political field, putting their actions and achievements in context and exploring issues raised by their lives, such as the use or rejection of violence, nationalism, or gender in political activism. While individuals are the subject of the books, their personal lives are dealt with lightly except insofar as they mesh with political concerns. The focus is on the contribution these revolutionaries made to history, an examination of how far they achieved their aims in improving the lives of the oppressed and exploited, and how they can continue to be an inspiration for many today.

Series Editors:

Sarah Irving, Kings College, London

Professor Paul Le Blanc, La Roche College, Pittsburgh

Acknowledgements

My heartfelt thanks must go out to everyone involved with Newcastle Universitys William Godwin: Forms, Fears, Futures conference in 2017, and the community of Godwin scholars across the world. I am immensely grateful to Professor Mark Philp for his encouragement, and this book is stronger and richer for the suggestions and advice of John-Erik Hansen.

Thanks must also go to David Castle and Robert Webb at Pluto Press for their patience with a first-time author.

Finally, the book would never have been written without the urging of Joshua M. Reynolds, or the support of Jen Edwards, Alex Burnett and Angharad Thomas.

1

Introduction The Anarchist

His contemporaries believed him to be the most important radical thinker of their age. William Godwin (17561836) was a political philosopher in the purest sense he wrote no great revolutionary speeches, nor did he ever issue a political manifesto. As the French Revolution careened from popular uprising to government terror, and from Directory to despotism, across the Channel British radicals pressed for parliamentary reform, womens rights and greater religious freedom. Godwin went further, questioning the most basic assumptions of government itself. Many of his peers were tried or imprisoned for their activism but Godwin, a lifelong critic of violence, and undeniably a theorist rather than an agitator, endured decades of abuse in the government-backed press because no political or criminal charges could ever be found against him.

William Godwin was an anarchist. He would not have understood the term in the way we do. He regarded anarchy in its popular sense, as a synonym for chaos. He recognised it as a creative chaos, however, and argued that its principal danger was that it created the conditions that might allow new (more brutal) authority to rise in its wake. Godwin was critical of authority as a principle, not merely its implementation, and believed that our ability to reason (if developed) would eventually make laws and government unnecessary. Godwin explained his ideas in An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793), written at the height of the French Revolution when it seemed as if the world had been pitched into the kind of creative chaos where anything was possible. Political Justice came to be regarded as one of the first major texts in the history of anarchist thought, exemplifying what is now (loosely) defined as philosophical anarchism the theoretical basis for anti-authoritarian principles and political action. Godwin himself was not a revolutionary. A quiet man, often shy among strangers, Godwin wanted to change the world through writing and conversation, recognising that educating people to reason for themselves was a more certain way of making things better than imposing better things on them.

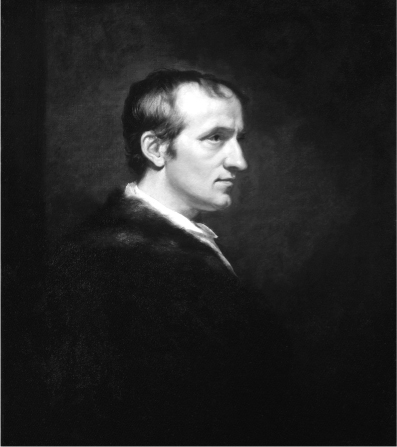

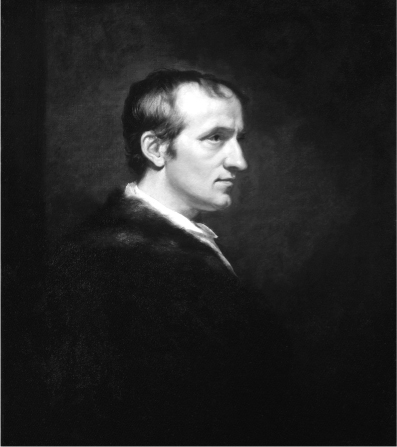

Figure 1 Godwin described James Northcotes 1803 portrait as the principal memorandum of my corporal existence that will remain after my death.

(National Portrait Gallery, London)

Anarchist is a word that conjures up images of revolutionary action, be it via the symbolic violence of the Black Bloc or the peaceful overthrow of the old social order in Catalonia at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. Yet it also describes a wide range of anti-authoritarian political thought, on both the left and right, united only by a common resistance to being told what to do. The word itself has an image problem: its literal meaning is simply to be without rulers but we have been told for centuries that, without rulers, the existing order of society would tear itself apart. We might cynically observe that the existing order could do with a shake-up, but few of us wish to do without order at all, and we have been led to believe that order is maintained through the exercise of authority of people giving orders and other people following them, with consequences for stepping too far out of line (because other people cant be trusted). Many anarchists would argue that order is simply something that happens when a group of people find out how to get along, and that most of the things that authority claims to protect us from are indirectly caused by authority in the first place (e.g. theft which is caused by inequality, which usually benefits those in power). Making statements about what anarchists think is, of course, a quixotic endeavour. Anarchism is a philosophy, but one that naturally defies rigid definitions. Anarchism has ideas, and it has thinkers, and it is easier to write about anarchisms (or the anarchism of a particular individual) than it is to discuss every school of thought under its umbrella.