The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

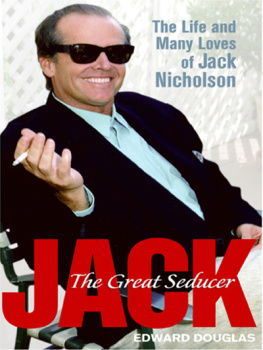

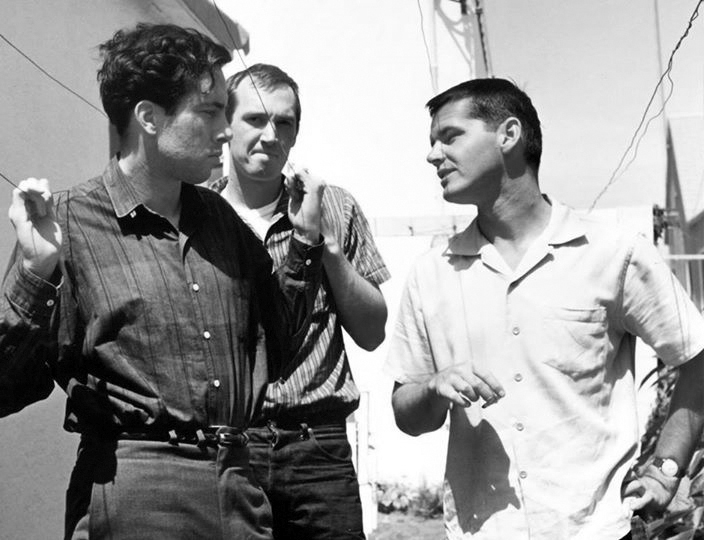

Jack Nicholson, a boy, could never forget sitting at the bar with John J. Nicholson, Jacks namesake and maybe even his father, a soft little dapper Irishman in glasses. He kept neatly combed what was left of his red hair and had long ago separated from Jacks mother, their high school romance gone the way of any available drink. They told Jack that John had once been a great ballplayer and that he decorated store windows, all five Steinbachs in Asbury Park, though the only place Jack ever saw this man was in the bar, day-drinking apricot brandy and Hennessy, shot after shot, quietly waiting for the mercy to kick in. Jacks mother, Ethel May, told him he started drinking only when Prohibition ended, but somehow Jack got the notion that she drove him to it.

Robert Evans, a boy, in the family apartment at 110 Riverside Drive, on Manhattans Upper West Side, could never forget watching his father, Archie, a dentist, dutifully committed to work and family, sit down at the Steinway in the living room after a ten-hour day of pulling teeth up in Harlem and come alive. His father could be at Carnegie Hall, the boy thought; he could be Gershwin or Rachmaninoff, but he was, instead, a friendless husband, a father of three, caught in the unending cycle of earn and provide for his children, his wife, his mother, and his three sisters. But living in him was the Blue Danube. That wouldnt be me, Evans promised himself. Ill live.

Robert Towne, a boy, left San Pedro. His father, Lou, moved his family from the little port town, bright and silent, and left, for good, Mrs. Walkers hamburger stand and the proud fleets of tuna boats pushing out to sea. More than just the gardenias and jasmine winds and great tidal waves of pink bougainvillea cascading to the dust, Robert could never forget that time before the war when one story spoke for everyonethe boy, his parents, Mrs. Walker and her customers, the people of San Pedro, America, sitting together at those sun-cooked redwood tables, cooling themselves with fresh-squeezed orange juice, all breathing the same salt air.

There was the day, many raids latera hot, sunny daywhen Roman Polanski found the streets of Krakw deserted. It was the silence that day that he could never forget, the two SS guards calmly patrolling the barbed-wire fence. This was a new feeling, a new kind of alone. In terror, he ran to his grandmothers apartment in search of his father. The room was empty of everything save the remnants of a recent chaos, and he fled. Outside on the street, a stranger said, If you know whats good for you, get lost.

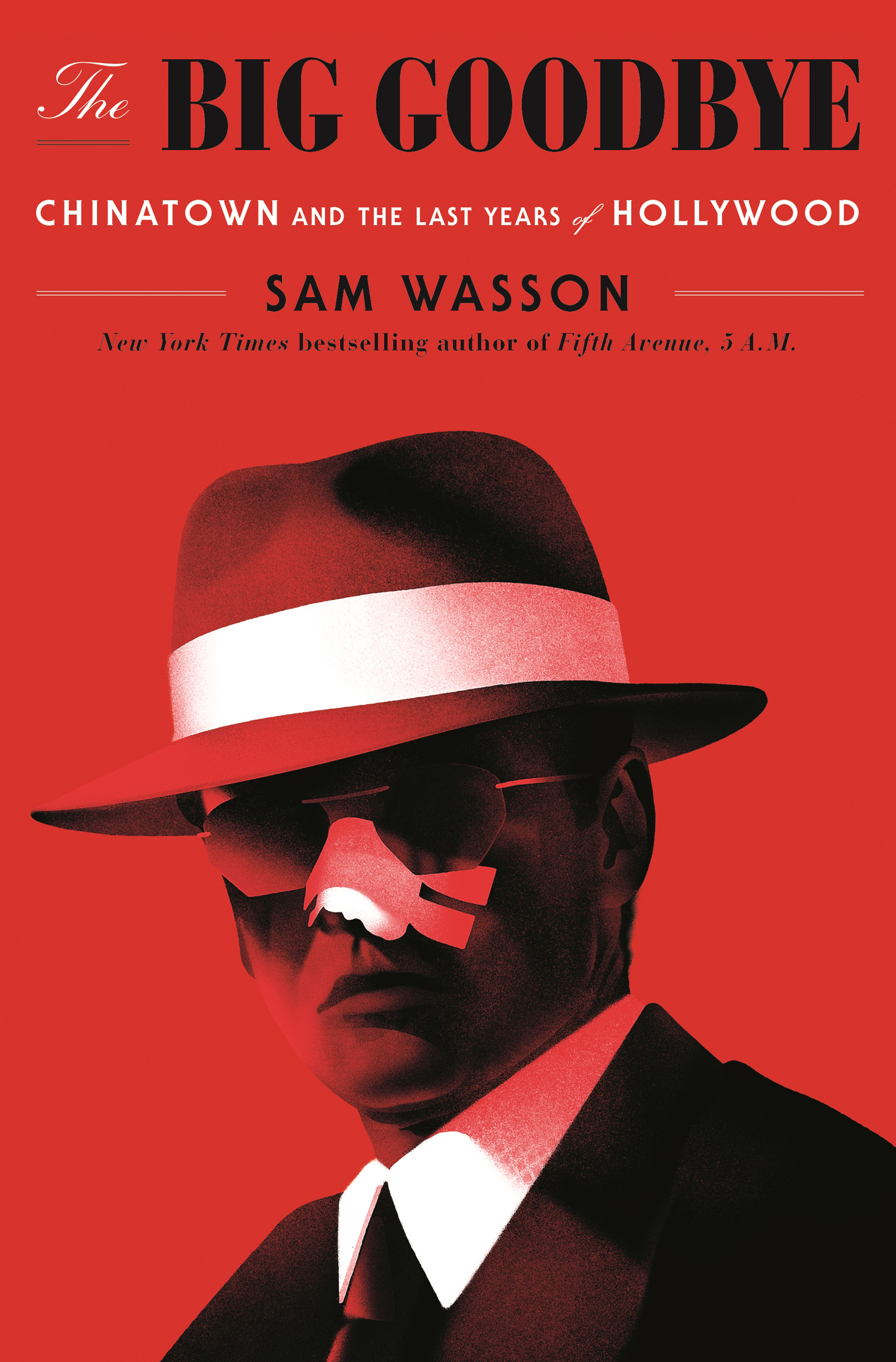

When these four boys grew up, they made a movie together called Chinatown.

Robert Towne once said that Chinatown is a state of mind. Not just a place on the map of Los Angeles, but a condition of total awareness almost indistinguishable from blindness. Dreaming youre in paradise and waking up in the darkthats Chinatown. Thinking youve got it figured out and realizing youre deadthats Chinatown. This is a book about Chinatowns: Roman Polanskis, Robert Townes, Robert Evanss, Jack Nicholsons, the ones they made and the ones they inherited, their guilt and their innocence, what they did right, what they did wrongand what they could do nothing to stop.

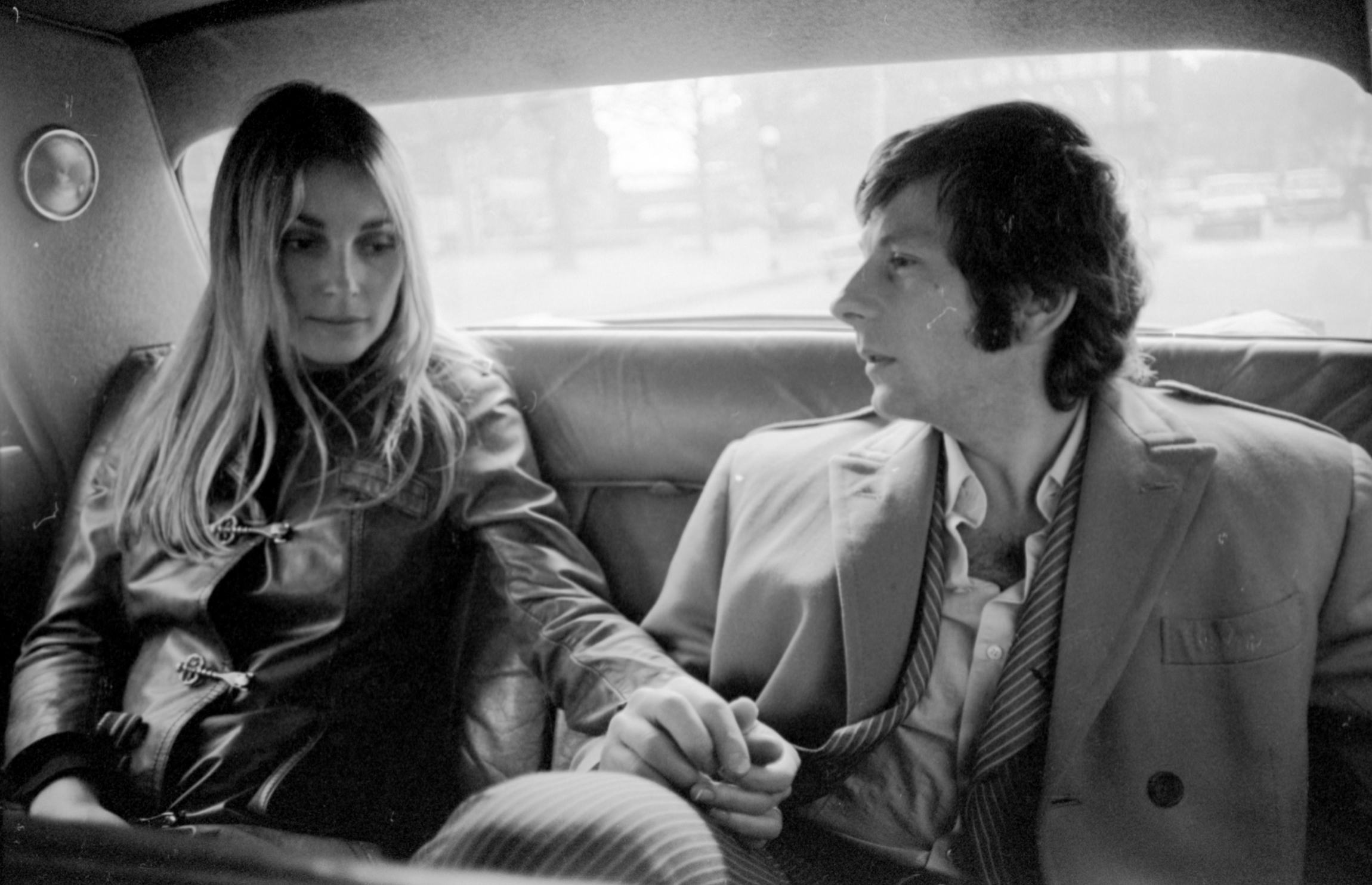

Sharon Tate looked like California.

Studying her from across the restaurant table, Roman Polanski could see it was impossible. She was laughably wrong for the part. He needed a burnished, preferably Jewish look, the kind of wintry shtetl waif Chagall might have painted onto a black sky. Polanski had named his character Sarah ShagalShagalfor that reasonand, with Roman, there was always a reason. He had deliberately set The Fearless Vampire Killers against the heavy, fragrant bygones of the Eastern Europe of his childhood, his home before the Nazis, before the Polish Stalinists. But this girl was as Eastern European as a surfboard; casting her, he would desolate, again, all that they had desolated before.

There was no reason, therefore, to continue the meal. In factas Roman had explained, quite clearly, to Sharon Tates manager, Marty Ransohoffthere really was no reason to have this dinner in the first place. But Ransohoff, in addition to managing Tate, was producing Vampire Killers, and had insisted on the meeting. Forget her inexperience, he implored Roman. Shes a sweet girl and shes very pretty and shes going to be a big, big star. Trust me. Ive seen thousands of girls, and Sharons different. Shes the one. Trust me. Ransohoff is a perfect example of a hypocrite, Polanski would come to understand. Hes a philistine who dresses himself up as an artist. Why hadnt Roman recognized the type earlier? He had never worked with a Hollywood producer, but he was no naf. He knew the stories; they were all the same: Well, the producers always said, we love the rushes, we love the dailies. What youre doing is great, but can you do it cheaper and faster? Creative dinners like these were precisely the sort of feigned artistic roundelays, so agonizingly familiar to Hollywood code and conduct, that made him want to throw down his napkin and run screaming, back to Repulsion, back to Knife in the Waterfilms he made his way, the European way, according to his reasons.

But Roman did not throw down his napkin. Instead he let the girl knowin little ways, silences, mostlythat he did not want to be there.

When Roman reported back to Ransohoff the next day, Ransohoff insisted on a second dinner. Find something for her, Roman, he said.

They had another dinner, this one worse than the first. Polanski could see she was trying to impress him, an Oscar-nominated director, talking, babbling, laughing too much. But he was not impressed.

Still, after dinner, walking through Londons Eaton Square, he tried to embrace her. She recoiled and ran home.

This, Polanski recognized, was his old behavior. He knew that his attraction to Sharon, or any woman, stirred in him feelings of terrible sorrow as ancient as long-lost wars. For years now, the certainty of loss had corrupted his every longing, and his resultant sadness summoned up the worst in him; for it was better, life had showed him, to be sorry than safe. So he would make himself superior. He would be arrogant, callous, abrupt; with women, and there were many women, he would lie and cheat and hurt. Over the course of those first two dinners, he would reduce Sharon to the size of her own waning self-esteem, and then, in the days and nights to follow, he would admonish himself for doing it. It was a pattern. He knew that. And he knew the reasons. He didnt like it, but it made sense.