The First True Hitchcock

The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Robert and Meryl Selig Endowment Fund in Film Studies, established in memory of Robert W. Selig.

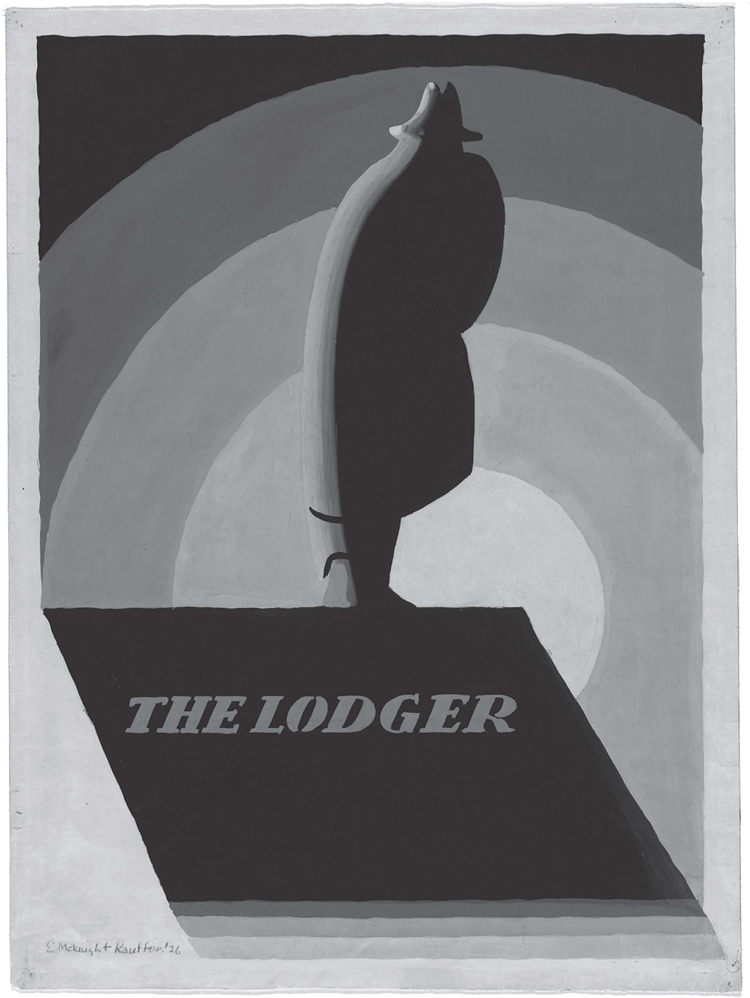

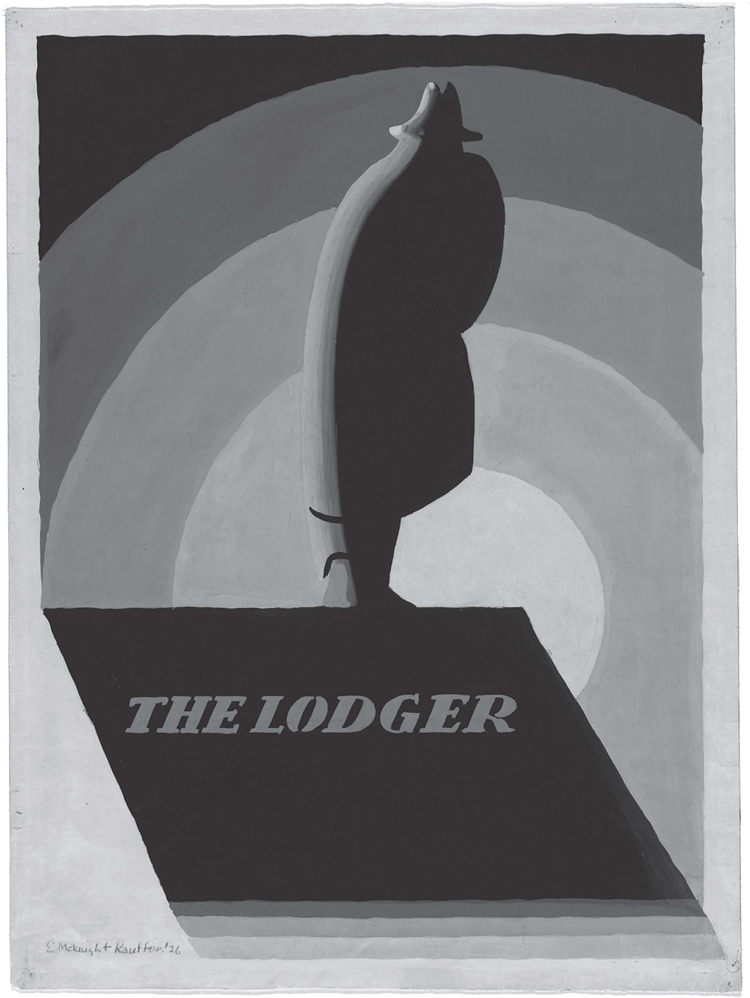

Edward McKnight Kauffer (18901954): Poster design for The Lodger, 1926. Tempera on paper; 29 21 in. (74.3 55.2 cm). Museum of Modern Art, 389.1939. Gift of the artist. Digital image 2021 Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence. Original Simon Rendall.

The First True Hitchcock

THE MAKING OF A FILMMAKER

Henry K. Miller

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2022 by Henry K. Miller

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Miller, Henry K. (Editor), author.

Title: The first true Hitchcock : the making of a filmmaker / Henry K. Miller.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021033060 (print) | LCCN 2021033061 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520343559 (cloth) | ISBN 9780520343566 (paperback) | ISBN 9780520975033 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Hitchcock, Alfred, 18991980Criticism and interpretation. | Lodger (Motion picture : 1927) | Motion picturesProduction and directionUnited StatesHistory. | BISAC: PERFORMING ARTS / Individual Director (see also BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Entertainment & Performing Arts) | PERFORMING ARTS / Film / Genres / Horror

Classification: LCC PN1997.L646 M55 2022 (print) | LCC PN1997.L646 (ebook) | DDC 791.4302/33092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021033060

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021033061

Manufactured in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Preface

The story of the making of The Lodger has been told many times. Hitchcock used it as a model of suspense, and to illustrate the role of blind chance in his life. It goes like this: While the distributor C. M. Woolf watched the film unspool, forewarned by his underlings that it was no good, Hitchcock and his assistant director and fiance Alma Reville tramped the streets of London in an agony that was not relieved when they returned to the studio to be told that The Lodger was being shelved. It was Hitchcocks third film, and his career was in the balance. But a few months later Woolf had a change of heart. The Lodger was shown to critics in September 1926 and acclaimed as the greatest British picture ever made. For Hitchcock himself it was the first true Hitchcock movie.

Nevertheless, The Lodger is also a silent movie, not in pristine condition, and known largely as a handful of stills and a few clips. Such a film, from the land and the age of P. G. Wodehouse, might well have been put on the shelf in a fit of distemper, then taken off it on a whim. Film history is full of harmless apocrypha of this kind, but the story of The Lodger is the seed of something more substantial. On occasion Hitchcock admitted that one or two changes were made to the film before its belated unveiling, and the editor responsible for these improvements, Ivor Montagu, was happy to provide the fine-grained detail that Hitchcocks version of the story left out. Montagus account has been highly influential on our understanding of Hitchcocks formation as a director.

In a pair of essays in his book Paris Hollywood, essays which led me to study this period, Peter Wollen made the particular story of Hitchcocks exposure to the influence of German and Russian films at the storied Film Society, of which Montagu was chairman, an integral part of a wider perspective on class and culture in Britain.

My doubts about Hitchcocks story, and Montagus additions to it, began to be confirmed in a series of fragmentary discoveries in the British Library Newspapers facility at Colindale, North West London, and in the special collections department of the British Film Institute, in 20067. I saw correspondence from one of Montagus friends about his dealings with Miss Reville, flashes of professional envy, esoterica about release dates. All PhDs must have a thesis, and mine was that the role of the Film Society had been exaggerated in a variety of ways. The Lodger served as a paradigm, and my discoveries helped me to make an alternative case. Still, it was a somewhat negative case. If not under the tutelage of the Film Society, how had Hitchcock become Hitchcock?

Hitchcock himself tells us very little. All the accumulated interviews add up to not much, and without diaries or letters his inner life remains a blank. The solution devised by his best-known biographer Donald Spoto was to treat the films as astonishingly personal documents. Hitchcocks outer, social life is almost as hard to make out, especially for the years before he joined the film business. The extent of his piety, as a Catholic in a more or less Protestant, increasingly irreligious country, is hard to gauge. He seems to have managed never to have expressed a political opinion. On the subject of films, and the books and plays that inspired them, he was more forthcoming, but even here the texture of his life as a filmgoer remains out of reach.

By the time he made The Lodger, in early 1926, Hitchcock was becoming a public figure, and he may be observed in the act of filming. But the first true Hitchcock was not brought to the screen by Hitchcock alonenor indeed by Hitchcock and Montagu, or any other combination of individuals. What happened in the summer of 1926, between The Lodgers shelving and unshelving, involves Harold Lloyd, the British governments deliberations on free trade, and a fortune in South African diamonds. Or, to move from the specific to the general, it involves Britains place in the world after the catastrophe of the Great War, its fraying Empire, its relationship with the newly great power across the Atlantic.

Only from about the year 1926 did the features of the post-war world begin clearly to emerge, wrote T. S. Eliot in 1939, and not only in the sphere of politics. From about that date one began slowly to realize that the intellectual and artistic output of the previous seven years had been rather the last efforts of an old world, than the struggles of a new. Though it was probably not at the forefront of Eliots mind, this was true of the sphere of cinema. A salient feature of the early postwar period, as seen from London, was the virtual supremacy of the American film. But in the year between the start of production on The Lodger and its general release in early 1927, that supremacy was made to become mere advantage. In this respect, and in others, the making of The Lodger straddled old and new worlds.

Hitchcock had served his apprenticeship in the old world, in the years of American supremacy. As Wollen wrote in his essay Hitch: A Tale of Two Cities, Hitchcocks London was closely connected to Los Angeles from the start. He was a boy when the picture theaters began to be built before the war, a youth when Mary Pickford became the worlds sweetheart, and barely of voting age when he got his first film jobat an American studio in London. Most of the films that he worked on in the early 1920s, as he rose through the ranks in a British film industry that was struggling to survive, had American stars, including the first two features he directed. Eventually, in the year Eliot made his pronouncement, Hitchcock went to Hollywood, a decision that now seems as natural as Hollywoods dominance over the worlds screens, and of a piece with it. Shortly afterward he attempted to remake

Next page