British Film Institute 2014

Preface, introductory material, annotations and editorial arrangement Henry K. Miller 2014

Article 6.6 translation Yvonne Salmon 2014

For all other copyright information see source details at the end of each article. Used with permission.

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 610 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The author(s) has/have asserted his/her/their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2014 by

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN

on behalf of the

BRITISH FILM INSTITUTE

21 Stephen Street, London W1T 1LN

www.bfi.org.uk

Theres more to discover about film and television through the BFI.

Our world-renowned archive, cinemas, festivals, films, publications and learning resources are here to inspire you.

Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martins Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave and Macmillan are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries.

Cover images: (front) couch; (back) Tonite Lets All Make Love in London (Peter Whitehead, 1967), Lorrimer Films

Designed and set by couch

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-1-84457-451-3 (pb)

ISBN 978-1-84457-452-0 (hb)

eISBN 978-1-83871-880-0

ePDF 978-1-83871-881-7

CONTENTS

It is tempting to believe that film culture has changed as much in the twelve years since Raymond Durgnats death as in the half-century during which he was a published critic. His byline belongs to an almost vanished world of print magazines. Durgnat wrote for Film, Films, Film Comment, Film Quarterly, Film Dope, American Film and, especially, Films and Filming. Sometimes he was found in Art and Artists and Books and Bookmen too. He contributed to Cinim, Cinema, Cineaste. For a time he co-edited Motion and was given space in Movie. In two discrete periods he appeared in Sight and Sound and the Monthly Film Bulletin. In the late 1960s he was a presence in IT and Oz; and, in the same years, in the Burlington Magazine and the British Journal of Aesthetics. He also wrote for Positif and Midi-Minuit Fantastique.

Yet what he wrote anticipated our digital age. Ten years from now, he wrote in 1968, movies may be as throwaway as pen and paper. Ten years later he foretold the end of cinemas magnificence. With pocket TV sets, people will be able to watch movies as they sit on a bus or train, stopping and starting when its convenient. For the first time in history, he wrote in 1982, the cultures of all times are simultaneously available. Its less like enjoying a vantage point than drowning in information. He predicted that Word and image processors plus video cameras plus computer mail and networking plus videotapes will let everybody cook up his own moving image-text combos. Well before the possibilities of digital image manipulation had begun to be realised, Durgnat championed films which went beyond the limitations of photographic realism.

Far from being trapped in time, he has come into his own. Though this book pays tribute to the very diverse band of publications in which its contents first appeared by simulating their various house styles, it is meant for the present.

Over the years of its gestation I have incurred many debts to colleagues, friends and family. I want to thank in particular Patricia Aske; Rebecca Barden; Charles Barr; Justin Bengry; Judy Bloch; Donald Brett; Liz Bruchet; Ian Christie; Michel Ciment; Richard Combs; Sophia Contento; Kieron Corless; Paul Cronin; David Curtis; Manolis Daloukas; Gareth Evans; Will Fowler; David Gale; Nancy Goldman; Jean-Pierre Gorin; Brian Hunter; Ian Johnson; Stella Keen; Lucinda Knight; Brighid Lowe; Tom Luddy; Hannah Mowat; James Naremore; Neil Parkinson; Frank Pike; Al Rees; James Riley; Jayne Ringrose; Jonathan Rosenbaum; Yvonne Salmon; Melanie Selfe; A. C. H. Smith; Rob Vasey; Edwin N. Vidler; Rob White; Peter Whitehead; Emma Wilson; Leila Wimmer; Mandy Wise; and the staffs of the BFI Library and Cambridge University Library.

Henry K. Miller, Cambridge, 2014

The editor and publisher also wish to thank Kevin Gough-Yates for permission to reproduce work by Raymond Durgnat.

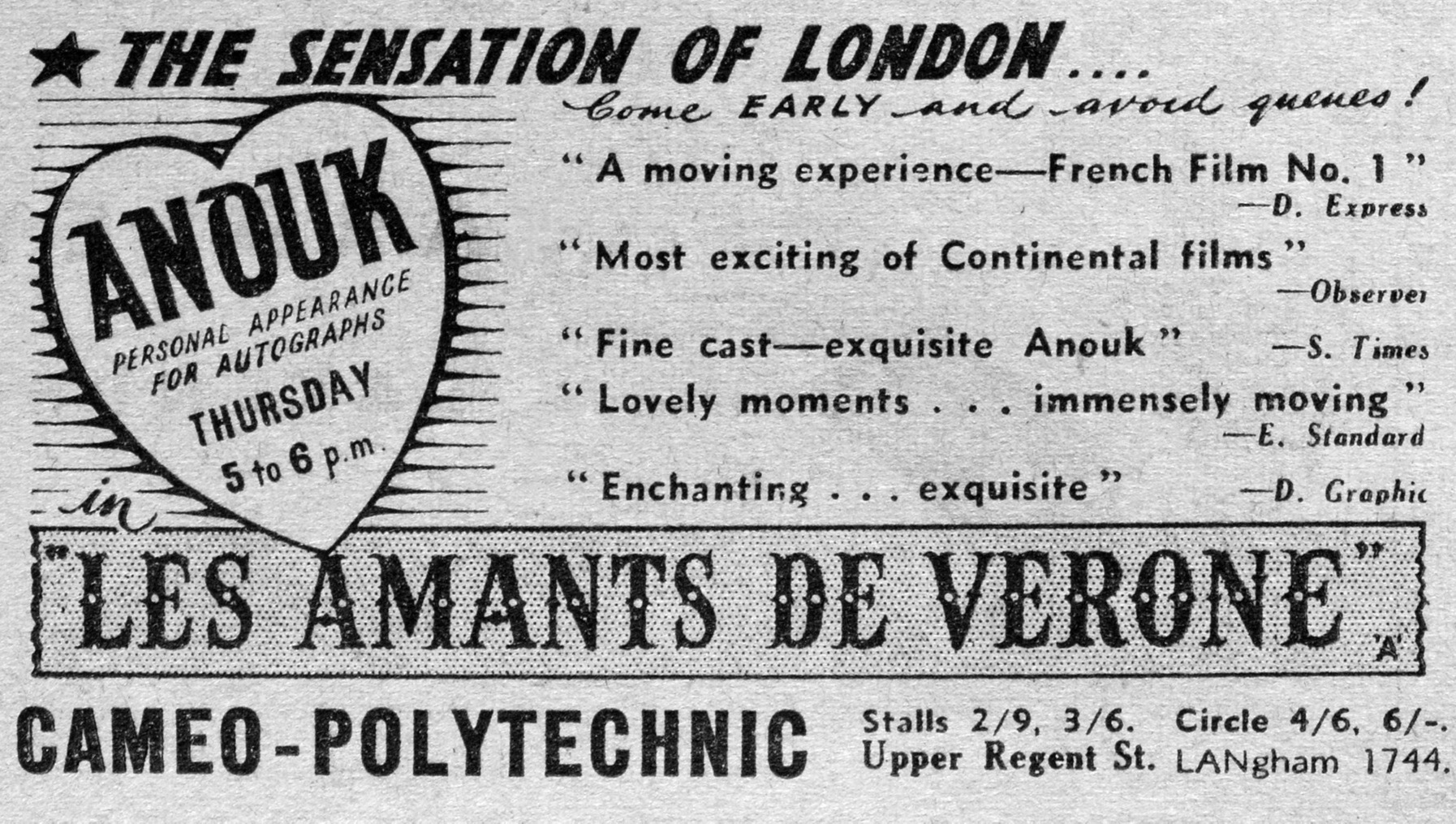

Evening Standard, 29 November 1949

As a schoolboy, Raymond Durgnat recalled in 1965, I often played truant to go to the pictures, and now that Im a lecturer in Studies Complementary to the History of Art Im an even firmer believer in the truancy theory of art.

In 1950 I went to see [Andr Cayattes] Les Amants de Vrone, eleven times in seven days. First to study [Jacques] Prverts crackling yet poetic dialogue, and then to try and remember exactly how it worked as a visual succession. I came away baffled, frustrated, with nothing to show but some visually illiterate sketches and a few sentences which I dared show nobody, so hopelessly trivial were they in terms of literary content.

But those images had hit me with their rhythm. They asserted the richness of a third dimension which in film criticism then was in its deepest point of eclipse: film as a graphic art.

Grammar School Eng. Lit., meanwhile, meant F. R. Leavis, the Great Tradition and attempted inoculation against the multitudinous counter-influences films, newspapers, advertising indeed, the whole world outside the class-room. Durgnat, a Baudelaire-reading jazz trumpeter who spent his weekends exploring Soho and the docks when not at the pictures, may have relished these counter-influences, but he was also a star pupil and editor of more than one school magazine. Nor were his teachers unresponsive: one sent an example of his work to Richard Winnington, film critic of the News Chronicle, and Winnington wrote back with encouragement. In December 1950 he won a place to study English Literature at Pembroke College, Cambridge, and a variety of scholarships to take him there.

At Pembrokes suggestion Durgnat took a year out, during which time he published his first articles in the British Film Institutes Monthly Film Bulletin