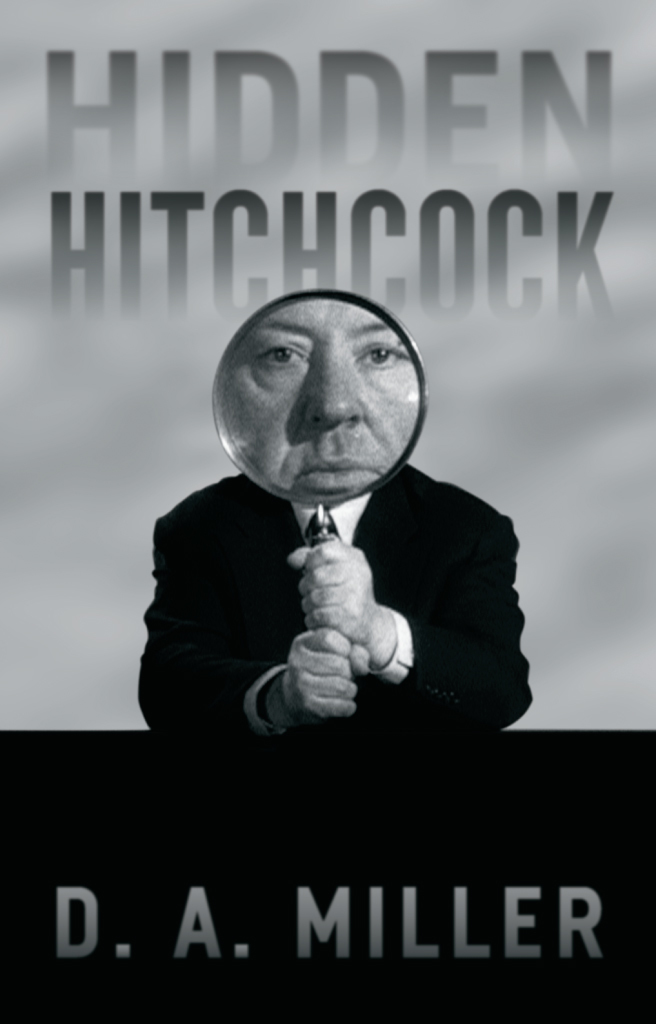

Hidden Hitchcock

D. A. Miller

The University of Chicago Press | Chicago and London

D. A. Miller is professor in the Graduate School at the University of California, Berkeley.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-37467-3 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-37470-3 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226374703.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Miller, D. A., 1948 author.

Title: Hidden Hitchcock / D. A. Miller.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015046038 | ISBN 9780226374673 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226374703 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Hitchcock, Alfred, 18991980. | Motion pictures.

Classification: LCC PN1998.3.H58 M55 2016 | DDC 791.4302/33092dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015046038

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Its as if I had one extra sense, one more than the others have, but not completely developed, a sense thats there and makes itself noticed, but doesnt function.

Musil

Contents

Even a work of criticism may be in danger of spoilers; sometimes, the less you know from the trailer, the better. And so I refrain here from offering a comprehensive summary that might eliminate any apparent need to read beyond it. Instead I present a short dossier of the key conceptions, forms, devices, and materials that will be set to work (harmoniously or not) in the essays to follow.

Public Style, Secret Style

Behind the impersonal detachment of a sovereign stylist, there often stands a damaged or disparaged person. Hitchcock is a famousand self-consciouscase in point. The homely fat man who appears onscreen only to decamp straightaway, as if he knew he were hopelessly out of place amongst cinemas beautiful people, is also the magisterial Auteur whose invisible hand has put these people in placeand will be bringing some of them, qua characters, to places they would never choose to be. The Hitchcock cameo always implies, along with his social abjection, the sado-artistic revenge he is taking for it from the pinnacle of cinematic mastery. And yet for all that, Hitchcocks antisocial malice must generally strike us as pretty mild, even jovial. Though the man shows himself hastily retreating from the social field, its demands and norms remain in force to determine the substance and style of the work. Typically, the plots devised by this onscreen loner dramatize the most basic social obligation: that formation of the Couple for which murder and mayhem are merely especially thrilling catalysts. And no film style has more successfully courted mass-audience understanding and approval than Hitchcocks. In his supremely lucid narrative communication, nothing deserves our attention that his camera doesnt go out of its way to point out. This cinema has plenty of ploys, but none it doesnt let us see through; suspense, the chief of these, depends precisely on forewarning us in such a way that our pleasure, if seldom unmixed with fear, is never spoiled by confusion. With a super-accessible style working hard to rehearse the emergence of the very unit of social organization, could there be (say at least until Psycho [1960] and The Birds [1963]) a more sociable author than Hitchcock?

I have been describing Hitchcocks manifest style, his style reduced to its universally intelligible and beloved codes. But as anyone who has seen a Hitchcock film knows, the director primes us to be considerably more alert than his spoon-feeding requires. In addition to our instrumental attention, we find ourselves possessed of a watchfulness that seems to have no object or use. Even when Hitchcock is not enjoining us to pay attention, we remain poised behind a pane of vigilance, as if expecting to see something besides his unmissable danger signals and loud significance alerts. But it appears we never do. Our vigilance stays on idle, never sufficiently roused to put undesignated objects under the focused scrutiny we obediently bestow on the designated ones. A strangely futile vigilance, it irritates our vision only by virtue of being palpably in excess of what we are being asked to see; ready to be as observant as Sherlock Holmes, we are challenged with only the most elementary cases. Inevitably, we cant help sensing that there is more to meet the eye in Hitchcock than, in his viewer-friendly manner, he arranges to greet the eye. To put the point bluntly, everything we are asked to see in Hitchcock feels a bit disappointing: a facade that blocks our view of all that we imagine we might see in the visual field. To watch a Hitchcock film is thus always to come under the spell of a hidden Hitchcock, and to want, somehow, to focus our attention on this imaginary thing or being. Whence the paradox of Hitchcocks cultural reception. On the one hand, he is widely regarded as having little to say (a pure entertainer who toils in the empty thriller genre); on the other, his stand-out style is the object of an enormous fascination that those who feel it hardly know how to explain.

This excess attention no doubt accounts for the pronounced tendency of Hitchcock criticism to close-read his films. Even before the home-system revolution democratized the practice, critics like Raymond Bellour and William Rothman worked from prints that they would dissect shot by shot and sometimes virtually frame by frame. With their editing table or Lafayette analyzer, these great close viewers did what most of us only dreamed of doinguntil the day when, with that thaumaturgic genie successively known as a Betamax, VHS, or DVD player at our command, we could attempt it ourselves. And yet, by and large, even such close viewing remains in thrall to the primacy of a films narrative structure; You might say that it repays attention in a double sense. Not only is it demonstrably worth everyones time and effort; it also seconds the priorities of our nave first attention. In its own sometimes abstruse way, it piggy-backs on the social uptake of Hitchcocks public style.

It is my project here to trace a different, more devious route taken by the surplus scrutiny that Hitchcock mobilizes in us. In contrast to the games that he is known to play with his Pavlovianly trained mass audience,as not to be seen, or a narrative image secretly doubling for a figure of speech in the manner of a charade, and you will have anticipated three key subtypes of Hitchcocks hidden picturing. I take all such hidden pictures as sporadic but insistent marks of a perverse counternarrative in Hitchcock that for no reasonor for no good enough reasontakes the viewer out of the story and out of the social compact its telling presupposes. Into what is hard to say. Structurally, the hidden pictures resist being integrated into the narrative or any ostensible intentionality; and whatever we might say about any one of them as a species of content falls markedly short of accounting for their enigma as a recurring form of Hitchcocks film-writing. It is as though, at the heart of the manifest style, there pulsed an irregular extra beat, the surreptitious murmur of its undoing that only the Too-Close Viewer could apprehend.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).