LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2248-4

ISBN 9781476622484 (ebook)

2016 Marc Raymond Strauss. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

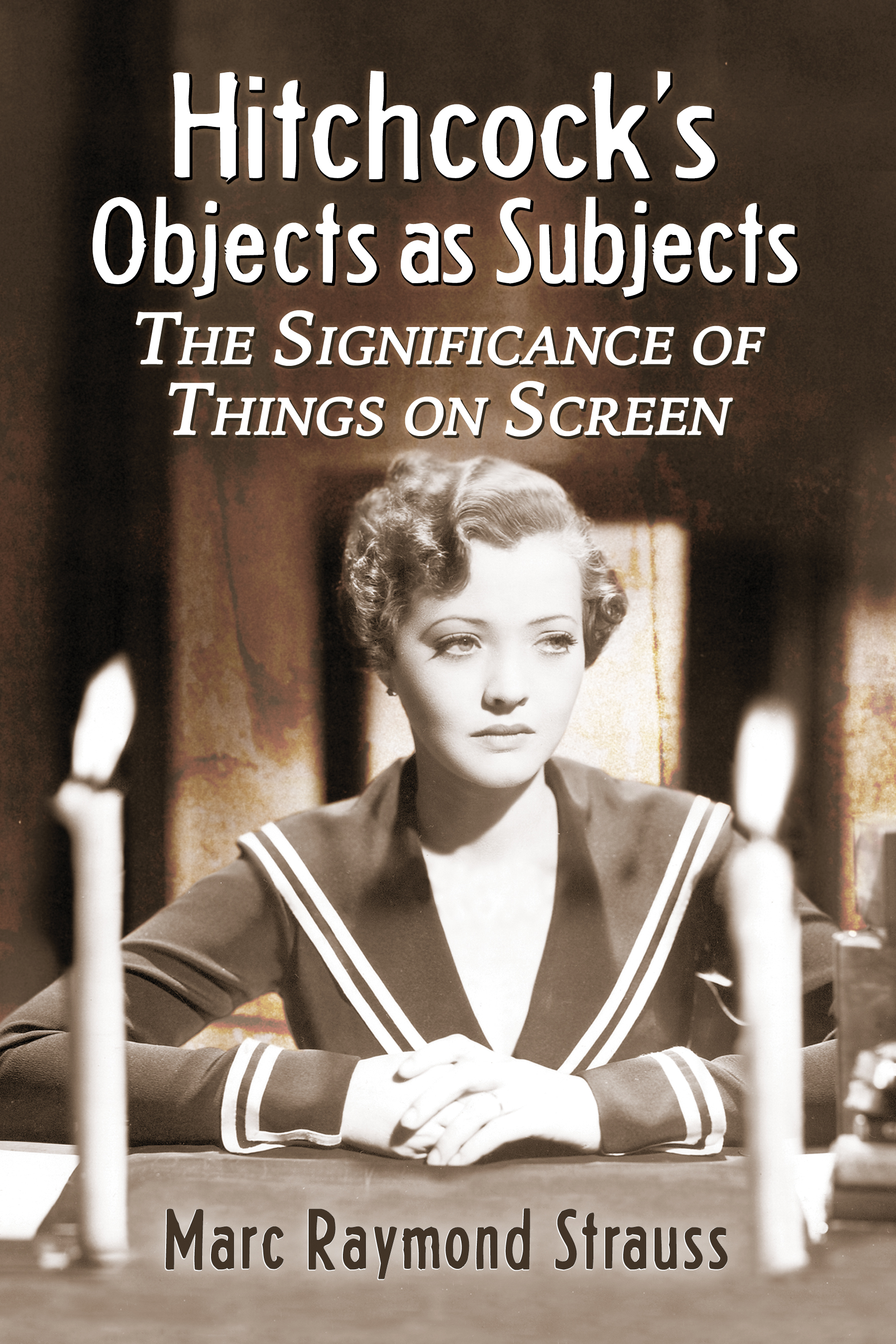

On the cover: Lighted candles, placed as they would be used on an altar, frame Sylvia Sidney in Sabotage, 1936 (Gaumont British/Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To my wife, Sarah Riley,

whose artistry never ceases

to inspire me

Preface

This book is about the objects in Alfred Hitchcocks films that are treated as subjects, equal protagonists to the human actors. Every detail that is visible on Hitchcocks screen carries with it information that impacts the audience; the importance of objects as subjects, while noted from time to time in other writings on the director, has not been given comprehensive attention until now.

I became interested in these elements while studying Hitchcocks films, realizing that his objects seemed to move about the frames like human characters, with human characteristics and qualities that impacted those people and my responses to them. I cover objects such as lamps, staircases, chairs, sculptures, tables, cars, and buildings that recur in many films over the directors fifty-plus years of filmmaking, to help the reader better appreciate their place in moving an audience.

I screened all 52 extant Hitchcock films numerous times as well as many of the major texts on the director and his work written since 1957 by the French critics-directors Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol. These important published works are essential to developing a richer context for this book, but mine is the first to focus solely on objects as subjects in Hitchcocks canon.

Introduction

One idea, for instance, is that Id like to do twenty-four hours in the life of a city. It starts out at five a.m., at daybreak, with a fly crawling on the nose of a tramp lying in a doorway. Then, the early stirrings of life in the city. Id like to try to do an anthology on food, showing its arrival in the city, its distribution, the selling, buying by people, the cooking, the various ways in which its consumed. What happens to it in various hotels; how its fixed up and absorbed. And, gradually, the end of the film would show the sewers, and the garbage being dumped out into the ocean. Thematically, the cycle would show what people do to good things [Hitchcock; cited in Truffaut, 1967, p. 241].

The 52 extant, full-length films of Alfred Hitchcock remain as fascinating today as when they were releasedand then re-released, transferred to video (Betamax first, for those who remember, and then VHS), videodisc (or laser disc, a short-lived format), DVD, Blu-ray, and now streamed. They can be played again and again with slow motion, pause, rewind, and fast forward. Their popularity remains high nearly forty years after his death, resulting in books and articles still published annually at a steady rate. Twentieth century geniuses like HitchPablo Picasso, George Balanchine, Igor Stravinsky, Martha Graham and the Marx Brothers come to mind, tooare palpably stimulating, endlessly compelling, and as bottomless as a well always full of fresh spring water. And lovers of these kinds of people feel compelled to return to the source for periodic sips and swallows.

Because of this never exhausted well, the directors characters, plots, music, actors, use of colors, silences, suspense, camerawork, mise en scnes, montage, exacting precision, planning, and artistry have been identified and analyzed to the nth degree. And yet, there still seems to be something new to spot and discuss in a Hitchcock film. That really is the definition of genius: Their work truly never dies. It persists, lasts, and in fact welcomes repeated scrutiny. Alfred Hitchcocks filmsmiraculously, happilykeep going and going and going, after the tenth or hundredth viewing.

And so, after that hundredth viewing, one naturally wonders: Can we whittle these elements down to one overarching quality that makes so many viewers, critics and movie lovers return to his films time and again? The answer is actually within the directors own comments and understanding of the potential power of film: Hitchcocks goal was to find the best ways to capture, keep and emotionally move the viewer as if he/she was a participant in the story on the screen, right alongside the other actors. In Franois Truffauts groundbreaking 1963 interviews with the director, Hitchcock/Truffaut: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock (Simon & Schuster, 1967), Hitchcock himself speaks about his imperative to evoke audience emotion. Here are just four:

Whichever way you choose to stage the action, your main concern is to hold the audiences fullest attention. [One] might say that the screen rectangle must be charged with emotion [p. 43].

Technique should enrich the action. One doesnt set the camera at a certain angle just because the cameraman happens to be enthusiastic about that spot. The only thing that matters is whether the installation of the camera at a given angle is going to give the scene its maximum impact. The beauty of image and movement, the rhythm and the effectseverything must be subordinated to the purpose [p. 71].

Planting the camera in the countryside to shoot a passing train [in North by Northwest] would merely give us the viewpoint of a cow watching a train go by. I tried to keep the public inside the train, with the train. Whenever it went into a curve, we took a long shot from one of the train windows [p. 202].

My main satisfaction is that the film had an effect on the audiences, and I consider that very important. I dont care about the subject matter; I dont care about the acting; but I do care about the pieces of film and the photography and the soundtrack and all of the technical ingredients that made the audience scream [in Psycho]. I feel its tremendously satisfying for us to be able to use the cinematic art to achieve something of a mass emotion [p. 211].

If, indeed, the effect of mass emotion on audiences is the most important thing in a Hitchcock film, everything that appears onscreen must therefore be subordinate to that dictum: actors, narrative, set design, art direction, sound, all that we see and hear and feel. All these carefully chosen details must also necessarily include every object that appears in the frame. Immobile objects that we repeatedly and deliberately find carefully placed within Hitchcocks frames are highly charged: house-bound items such as chairs, stairs, walls, lamps, bedknobs, candles, windows, pictures, desks, glasses, and cups, as well as more public ones, both immobile and mobile, such as buildings and homes in towns and cities, the cities themselves, and trains, buses, cars, planes, boats, etc. Carefully placed alongside the actors and art direction and sound design, these objects have an equally powerful effect on an audience in Hitchcocks hands.

[The] term vehicle seems to be the only one to account for all the trains, planes, automobiles, skis, boats, bicycles, wheelchairs, etc., which haunt [Hitchcocks] universe. We receive them not only as a sign of passage from one world to the other but especially as a sensation. A sensation of being carried off [Deutelbaum and Poague, 1986, p. 14].

Next page