KERALA'S NAXALBARI

Ajitha: Memoirs of a young revolutionary

KERALA'S NAXALBARI

Ajitha: Memoirs of a young revolutionary

Translated by

Sanju Ramachandran

To the memory of Kunnikkal and Mandakini Narayanan and Comrade Varghese

S RISHTI P UBLISHERS & D ISTRIBUTORS

N-16 C. R. Park

New Delhi 110 019

srishtipublishers@yahoo.com

First published by Srishti Publishers & Distributors in 2008

Copyright original language with Ajitha

Copyright English translation with Sanju Ramachandran, 2008

ISBN 81-88575-63-1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers.

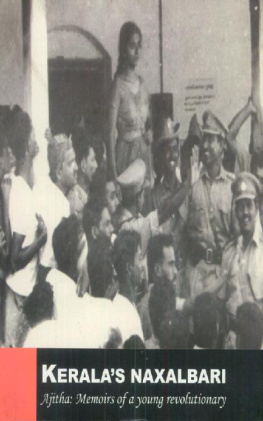

Foreword by the translator

On the night of November 24, 1968, a group of sixty determined to change the world, ran over a police station in the forests of Western Ghats. One of them was a girl, young enough to be a senior secondary student. The group hacked to death a wireless operator, fatally wounded an inspector and then went on to distribute the hoarded wealth of the feudal lords who had made slaves of tribal women and men, trading them in village fairs and binding them in perpetual debt. They were declared murderous dacoits by the media, the young woman's photograph was splashed everywhere as a warning and also to help law-abiding citizens to hand her over to the police. Soon the people for whom they had launched the revolution got hold of a few of them including the woman. Policemen, raining blows on her, forced her to shed her sari and her woolen pullover. In the courtyard of the local police station, on a raised platform where the policemen hoist the national flag and salute it on special occasions, they paraded the teenager in her blouse and trousers, which she was wearing under her sari. They called out to the huge crowd, "This is how she roamed around the forests with her men," thus, pronouncing her a whore. Journalists clicked away in great haste. With policemen all around her laughing, abusing and egging on the crowd to debase them, she stood next to the flagstaff, helpless, trembling, yet undefeated. She glared at the horizon from where her sun failed to rise. Thus was born, the poster woman of Kerala's Naxal movement.

Sacrifice is a tough notion to understand, particularly in the market place, that is life today. One wonders why some leave a normal life, home, relatives and the secure environs of a middle class existence to launch themselves into the unknown to deliver justice to a people with whom their only link is the human form. Perhaps justice, other than that which is prodded by expensive lawyers, has today become even more incomprehensible as an idea. My attempt in translating the memoirs of Ajitha was to make out why a young person from the city would go into the forests to fight people whom she had never seen, for people whom she had never seen. Of course, this was not an accidental 'drama in real life', but the result of a choice made out of ideological convictions, an analysis of forces that shape history and the result of a great deal of thought and planning, however flawed they be. This young person became a revolutionary and took part in an armed revolt when she was just 18. Sure, her father and mother were her senior comrades in the movement that was launched to get the villages to encircle the towns and bring in armed revolution in India. Ideology, no doubt, was the fuel. But what burned was a life. When Ajitha was released in 1977 from jail, she was only 27, but had spent almost nine years in jail, much more than the capital, many of our freedom fighters had accumulated to be pawned for positions of power.

Mandakini and Kunnikkal Narayanan were parents so different that, Ajitha's destiny was probably decided by her genes and the home she grew up than anything else. Narayanan, a Malayali and Mandakini, a Gujarati were comrades who as members of the undivided Communist Party of India, left their well-paying jobs in Mumbai and sought out revolution. Their journey continued from the CPI to CPI (Marxist) to CPI (Marxist-Leninist). Yet, Ajitha was an individual in every right and the choice was hers, because when the family plunged itself into the revolt, she was the only one who proceeded to the forest to attack a Malabar Special Police camp at Pulpally, while her father chose to lead the action in Thalassery town and Mandakini kept herself away from both.

The thunder of spring that struck Naxalbari in June 1967, was soon to echo in the forests of Kerala in November 1968 under the leadership of a man who had everything to lose and probably only others' happiness to gain by doing what he did. Varghese is no doctor like Che Guevara, nor a motorcyclist, definitely not handsome enough to have his mug on T-shirts, but he is the closest Kerala has in terms of the myth of the immortal revolutionary felled by the cruel system. He was the office secretary of the Kannur district office of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), that is, one of the key players in the citadel of the party from where apparatchiks rise to become Marxist chief ministers and party secretaries to manage huge amounts of party wealth and real estate. Had he been 'wiser', he could have been one of them. But he chose to be the adiyorude peruman, the headman of the oppressed, as the tribals still call him. He was from a family, which went from the plains to settle down and prosper in the mountain tracts of Wayanad. But instead of the peasants thirst for land and urge to prosper, Varghese had an indomitable will to have justice for fellow farmers and the most miserable people of Kerala, the tribals. Plays and novels have been written about this man. But Ajitha's memoirs offer us unique glimpses of Varghese as a leader, a comrade and a man full of kindness. The Naxalites of Kerala had always alleged that Varghese was tortured, eyes gouged out and brutally murdered by the Central Reserve Police Force on February 18, 1970 under orders from the State Government. Recently, a former CRPF constable owned up the murder saying that he could not carry the guilt of having killed a great leader any longer. The self-proclaimed murderer wrote recently that Varghese wanted to know exactly when he was to be shot. The constable opened his lips to let out a 'shoo' sound before firing straight into Varghese' heart. "Viplavam jayikkatte" (long live the revolution), the constable recalls Varghese's thunderous shout that rose above the gunshot. Naivete? The question pops up. Why did these people give away so much? For what? The system continues to be what it was. Have they all suffered in vain?

To come back to Ajitha, the girl of eighteen was beaten up, molested and even threatened with rape in custody. She was almost a mental wreck in solitary confinement. Yet, she shunned all offers of freedom, insisting on an unconditional release, wanting to be true to what she believed. And when that finally happened she wrote one of the finest political memoirs in Malayalam in 1979 for a periodical, insisting all throughout that she might have got defeated but not proved wrong. We still have no answers as to why certain people, honest and ordinary people, often middle class, give up everything for others and suffer unspeakable horrors and still remain proud of all that they had endured. Instead, these memoirs details graphically the lives of a few people who did that, a group that included Ajitha, another teenager Sukumaran, who was just a year older to her, and the elderly Kissan Thomman.

The fascinating story of Ajitha is also that of the first wave of Naxalites in Kerala. Curiously, she spends a lot of time explaining the cruelty of society towards women. In fact, the latter chapters are about her life in jail, which reveal the miserable conditions of Indian jails and also the misery in the women's ward. Unconsciously, she was undergoing a transformation. In the preface to the second edition of her book in 1993, Ajitha declared that she was no longer a member of the Naxalbari movement and that she is a confirmed feminist, a Marxian feminist. Even the short 1993 preface had a scathing feminist critique of the Naxalite movement: "Even while in the movement, I used to get upset by the denial of opportunities on the basis of gender. There were occasions when the attitude towards women in the revolutionary movement was condemnable. At one level the 'men comrades' had a protective attitude towards 'women comrades' and at another level instead of being regarded as comrades, women were looked at as sex objects."

Next page