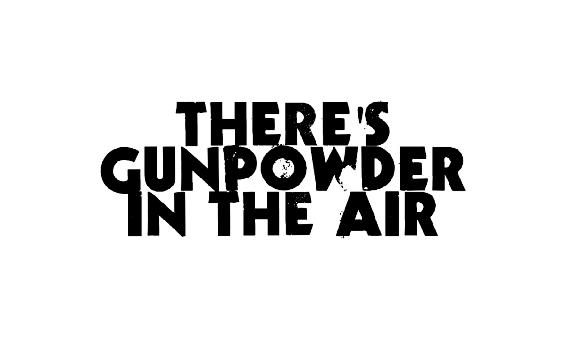

First published in Bengali as Batashe Baruder Gondho in 2013

Published in English in 2018 by Eka, an imprint of

Westland Publications Private Limited,

61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road,

Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095

Westland, the Westland logo, Eka and the Eka logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates.

Copyright Manoranjan Byapari, 2018

Translation copyright Arunava Sinha, 2018

ISBN: 9789387894440

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organisations, places, events and incidents are either products of the authors imagination or used fictitiously.

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

CONTENTS

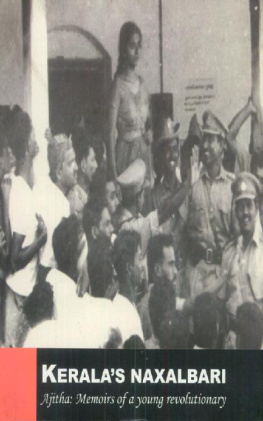

I was arrested by the police in late 1974 or early 1975. The charges included use of guns, use of bombs, disturbing the peace, and so on. I did have some connection with Naxals at this time, though the police did not know of it. They arrested me as a miscreant. Even the political party with which I had links did not consider me a party worker. To the police I was an antisocial goon. I used to consider myself a Naxal, as did my companions. But Naxals did not consider us one of them. They called us the lumpen proletariat.

The police arrested me early one morning at the place where I was hiding. I was taken to the police headquarters at Lalbazar and given the third degree. At first the police had expected to discover a huge stockpile of arms with me, but the officers were extremely disappointed when their search of the house I was arrested from yielded nothing.

They filed a number of cases against me, along with the thirty or so people they had arrested that day. It was in the lock-up in Lalbazar that I met Debashish Bhattacharya and Kallol Sengupta. We were presented in Bankshall Court and sent to Alipur Special Jail as under-trial prisoners.

I was there for nearly two years, undergoing trial the entire period. Then I was released on bail for Rs 1000, after furnishing a bond of Rs 100. The trial continued for two years more, during which time I had to appear in court for hearings. Eventually the case against me was dismissed.

I heard many stories from my fellow prisoners during those two years in jail. There were some people there who kept coming back. Prison was like a home to them. They told me stories too. That was when I heard the story of the jailbreak attempted by Paritosh Banerjee and his fellow Naxals from the Panchanantala area of Calcutta.

I had no thoughts of being a writer at that time. When I did begin to write later, it occurred to me to write the stories I had heard in prison. That is what I have done here, only changing the names of the characters.

Manoranjan Byapari

1 November 2018

H e appears to be about fifty, but is in fact far older. His moustache and hair are more grey than black now, his bright eyes radiate immeasurable curiosity. Manoranjan Byapari is a son of the soil. A writer, a former rickshaw-driver, and, since then, an able cook. He has no hesitation in identifying himself as a member of the Namasudra caste.

He wiped out the stigma of his own illiteracy in jail, driven by lofty ambition to embark on the journey of learning the alphabet at the age of twenty-four. This led to the highly unusual path of self-education that culminated in Byaparis becoming a writer. Describing his long solo voyage in his characteristically animated manner, he says, I was in jail then, in despair and unable to hide my anguish. That was when a man of about sixty became my confidante and inspired me in different ways. He had been convicted for cheating, which meant that this was his profession. You cannot succeed in this line of work unless youre very clever. It was a sort of game for him. He was the one who motivated me to become literate, explaining that educated convicts were given different kinds of work in jail that involved writing. This allowed them to practise their skills as well. But illiterate people could only be assigned physical labour. It was essentially on his advice that I taught myself to read through a very unusual process. This gradually opened up an unending horizon of knowledge.

It was after this that Byapari began to read literature. The first book I read was Manoj Basus novel Nishikutumbo ( Relatives by Night ), followed by Jarasandhas Louhokopat ( The Iron Gate ). Released from jail soon afterwards, he went back to his old profession of being a rickshaw-driver, in the course of which he happened to meet the renowned writer Mahasweta Devi. This acquaintance developed into a relationship which transported him to a world of unknown wonders. It was on Mahasweta Devis inspiration that I began to write. My first piece was published in her magazine Bartika . I was an avid reader back then, always asking people around me the meanings of words I could not decipher for myself. This was how I went from literacy to reading and, eventually, to attempting to write. The journey took six years.

However, when Byapari began writing, it was under pseudonyms such as Madan Dutta, Arun Mitra, and Jeejibisha (the Bengali word for lust for life). The intention of this expedition behind a concealed identity was self-examination. Enriched by the experiences of his community and his society, Byapari evolved into a writer, another Advaita Mallabarman, as it were. But he never wanted to position himself as a Dalit writer or as a citizen of the fourth world.

After the break-up of the Soviet Union, I was convinced there are only two classes of people, he says. As the old saying goes, the oppressor and the oppressed. Everyone is as tyrannical as they can be, and those who have no power suffer this in silence. But when the same people acquire power in some manner, they too exploit those who are less powerful than them. These things lead to issues that people revolt over, which in turn gives birth to leaders. In other words, the objective of human beings is to be authoritarian in one form or another. And in the course of fulfilling this objective, even those who are referred to as dalits become leading figures of society. There are plenty of examples of this. All it needs to be such a leading figure is money. It is only in the case of the poor and the illiterate that the question of caste comes up. No one cares about the caste of the wealthy, whose only identity is that they are rich.

What do I say about myself in this situation? To a high caste person Im a dalit, untouchable. To other dalits Im a rickshaw-driver. To other rickshaw-drivers Im a writer, and therefore untouchable as far as they are concerned. Those who are at the forefront of dalit movements now are educated people, even if they are low-caste individuals. Many of them are senior government officers, occupying high positions in the social hierarchy, in other words. Theyre playing out their leadership ambitions at the expense of dalits, to whom it makes no difference, for the dalit remains nothing more than a dalit. These leaders do not even consider their domestic servants human, and yet theyre leading dalit movements. Of course there are a few exceptions, as there always are. But my experience with the majority of dalit leaders has not been satisfying.

Next page