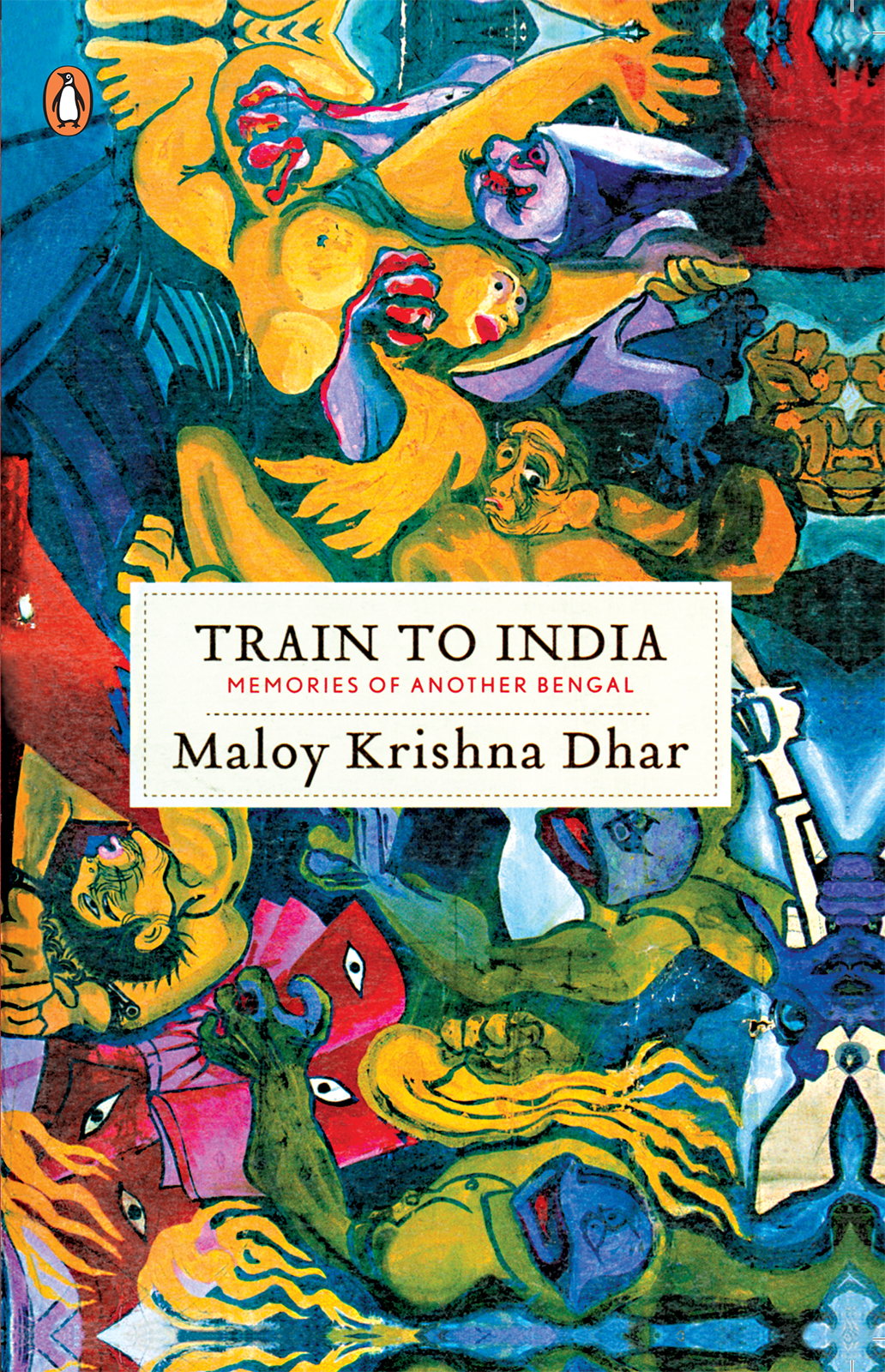

Maloy Krishna Dhar was born in Kamalpur, Bhairab-Mymensingh in East Bengal and migrated to West Bengal with his family during Partition. After obtaining a Masters in Bengali Literature and Language and Comparative Literature from Calcutta University, he worked as a college teacher and a junior reporter. He joined the Indian Police Service in 1964 and worked with the Indian Intelligence Bureau (IB) for three decades.

After retirement from a service that honed his ability to observe and understand people and their motivations, he has had an extremely successful career as a freelance journalist, contributing to all the major English dailies. He is also a best-selling author and his landmark books include Open Secrets: Indias Intelligence Unveiled, Fulcrum of Evil: ISI-CIA-Al Qaeda Nexus, Black Thunder: Dark Nights of Terrorism in Punjab and We the People of India: A Story of Gangland Democracy.

Dhar also manages the website www.maloykrishnadhar.com where research articles on security, terrorism and internal and international security are regularly updated.

ONE

In the Beginning

T he Great Exodus took survivors across imaginary lines drawn on cartographers maps, which promised them no home, land or manna from heaven. They waded through rivulets of blood and hillocks of skeletons but failed to negotiate the barrier of history. The Muslims of the subcontinent had a Promised Land after a brief cohabitation with their Hindu subjects for a mere period of 650 years. The British had earned the right to divide after a brief rule of about 170 years.

We, the supposed original inhabitants of India, had not received any promises. We, the Hindus and Muslims fought a common enemy, the slave masters who ruled us, with the assurance that we would have a Common Land, Our Own LandHindustan. It was not to be. We were being told that religion was the universal constant that determined the history and geography of a people.

The story of the Great Human Exodus has not been recorded faithfully. Hindus and Muslims wrote their respective histories, some perverted mutilation of history called the history of Hindustan and Pakistan. Historians, who evaluate and present history from their own perspective, often rationalize human tragedy with their own interpretations. We were offered Congress, communist, Hindu, Muslim, swadeshist and several wadeshist and several other versions of history. They dared not chronicle the pains of the Great Exodus because they were busy cushioning their chairs.

In the beginning, there was srishti-sthiti-binashanag shaktibhute sanatanithe Eternal Energy that caused creation, assured preservation, and inevitable destruction. The eternal energy of creation had endowed my village and part of Bengal with the sweet melodies of nature.

We, the Bengali speaking people living in our tiny corner of the universe and India were there with our rivers, the Meghna and Brahmaputra, the memorable Teetas Beel, Satmukhi Beel (the lake with seven inlets and outlets), paddy fields, orchards full of flowers, fruits, spices, ducks, herons, cranes, Bengal robins, finches and parrots, goats, cows and ponds full of fish.

I had my very own pets: Chandana the parrot, Pintu the white goat, Tomtom the dog and Sonai the duck. Mother had Victoria, the all-white furry cat.

There was everythingmy primary school, our teacher Dhiru Acharya, friends Lutf-un-Nissa (Lutfa), Jasimuddin (Jasim), Saifullah (Saifi), Mehboob Alam, Haripada, Mani and scores of cousins. Living next to the wild, moody and surging Meghna and Brahmaputra rivers, only a dead soul could escape the turbulent love of creation.

Bhairab, our lively railway station connected Calcutta, Dhaka and Mymensingh with the southernmost tips of east Bengal. There was the wonderful Anderson Bridge over the Meghna, the only bridge to span the turbulent river. The station unravelled new surprises, day in and day out, besides bringing in new faces and carrying away some known faces to destinations beyond the horizon. The station was our telescope to the outer world.

I dreamt of riding a train through the land I saw on the global map in the Bradshaw travel guide of India. It made me dream of boarding a train to explore other parts of India.

One fine morning in January 1945, as a boisterous child of six, I had my dream journey to Brahmanbaria, a town in Tipperah district. That short journey was preceeded by my obdurate persistence to accompany our family retainer Dhiru Saha. He had told me, in his exquisite poetic language, of the beauty and charm of Kanan Devi, the film actress, and the magical world of the Meghdoot cinema hall at Brahmanbaria. My nagging persistence led to admonitions but finally, mother yielded. She pushed eight annas (fifty paise) annas (fifty into my pocket and reminded me that Dhirus social mores were different from ours. Her decision irked a few elders and evoked the awesome admiration of my young cousins and friends. I took the dream journey with Dhiru, who figured in our lives like the occasional cyclonic hailstorm, mostly enjoyed and often rued.

Dhiru was a romantic. He gave me a nice rickshaw ride to the wonder world of Meghdoot, spoke about the beauty of young lasses, dumped me near a flower vendor and reappeared with a garishly dressed girl. I cant recall her name. She caressed me like an affectionate mother, ran her fingers through my hair and offered me a coloured ice cone. She accompanied us to the cinema hall where I was enchanted by the unreal world of celluloid fantasies. I did not notice the physical closeness of Dhiru and his girlfriend. Kanan Devis charms disappeared behind the silver screen and Dhiru sternly warned me not to mention the girl to anyone in the family.

I had plenty to babble about to my friends of my wonderful journey to the forbidden world of a cinema hall, the goodies I ate and the girl who had bewitched Dhiru more than Kanan Devi did.

Stories flew like wild fire. My story, garnished with imagination and many a twist had reached the inner chambers. My adventure finally landed me in the court of Grandpa Chandra Kishore, Dad Debendra, Uncle Birendra and the many women members of the family. Grandpa pronounced that I should be punished with three cane strokes, Dhiru with ten, and an amount of twelve annas should be deducted annas should be deducted from his grand monthly salary of five rupees for his acts of blatant indiscretion.

Mother Sushama got a scolding from Grandma Chandrakanta for her frivolous act of indulgence in permitting me to see an adult movie called Mane Na Mana (Mind Unfettered).

My mother was different. She did not mind her kids taking steps out into the uncertain world outside our village Kamalpur. She suffered quietly, served the needy and violated the strictest codes of Chandra Kishore. She was a sort of social rebel.