Byānārjī Mamatā - Didi: a political biography

Here you can read online Byānārjī Mamatā - Didi: a political biography full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: India;West Bengal;West Bengal (India, year: 2012;2013, publisher: HarperCollins Publishers India, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

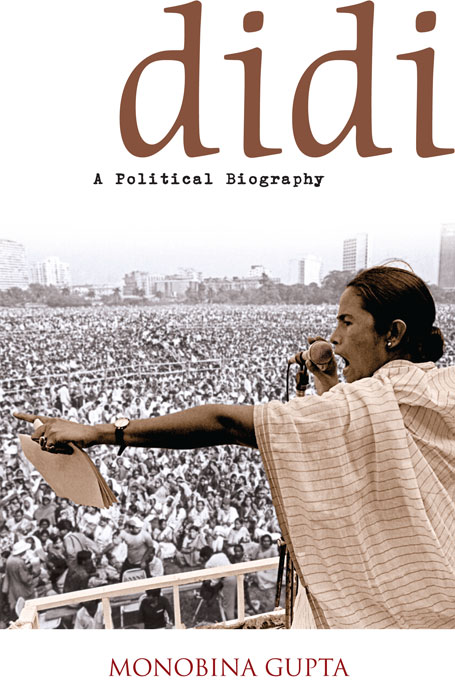

- Book:Didi: a political biography

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins Publishers India

- Genre:

- Year:2012;2013

- City:India;West Bengal;West Bengal (India

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Didi: a political biography: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Didi: a political biography" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Didi: a political biography — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Didi: a political biography" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For my parents

Milan Chandra and Manjari Gupta

Contents

M amata Banerjee has been known to evoke strong emotions. Her fans worship her fearlessness, her simple, ascetic lifestyle, even her melodramatic performances. To her political adversaries she is a stubborn fighter who has repeatedly returned to haunt them despite their attempts to browbeat her out of the political arena. Mamata reigns imperious and unchallenged over her somewhat amorphous party, the Trinamool Congress, which is now in power in West Bengal. In private conversations, Didis party colleagues tell you how terrified they are of Mamatas tempestuousness and her mercurial temperament. But even among sceptics who look down upon her non-gentrified ways, the Trinamool Congress leader inspires grudging awe.

This book tries to capture some of the complexities that make Mamata Banerjee what she is. In order to comprehend the different aspects of her persona, which often contradict each other, I have tried to contextualize Mamata within a broader framework of Bengals bhadralok culture and the religious and cultural elements which influence her politics and life. I have tried to understand Mamatas own perception of herself as a woman; her responses, if any, to feminism; the contradictions between her dictatorial and democratic impulses; and her appropriation of the Lefts culture and radical politics in recent years.

Through a study of books authored by Mamata, and interviews with her colleagues and cultural and human rights activists, I have situated the subject in the larger context of thirty-four years of Left Front rule. Though she experimented with coalitions led both by the Congress and the BJP at the Centre and headed important ministries in the Central government, her attention was always focused on one goal: defeating the Left Front government and coming to power in Bengal.

Written during the run-up to West Bengals historic 2011 polls, the book ends with Mamatas ascendancy to chief ministership. She has inherited a financially bankrupt and stagnating state, politicized to the core. Ironically, her predicament is somewhat like that of the Left Front when, through a bloody struggle against the Congress, it had first come to power in 1977. Hardened in the school of radical protests and agitations, the Marxists then knew little about governance and administration. Mamata, too, has followed a similar path. The people of Bengal now have high expectations from her and the new regime, not just for governance, but also for inaugurating a different political culture.

As the book goes into press, Mamata Banerjee has completed six months as chief minister. Many have done some hurried stock taking of her performance during this brief and dramatically eventful period. Some have pronounced harsh judgment, reprimanding her for continuing to be unpredictable and combative, and still acting more like a recalcitrant Opposition leader than the chief minister of a state. Less inclined to penning an early epitaph, more circumspect critics have adopted a calibrated approach in their assessment. Six months is too soon to come to any decisive conclusioneither by unequivocally endorsing, or by rubbishing her altogether. Nasty controversies have already erupted, dragging Mamata into the conflict zone of ideas, policies, politics and personalities. But this was hardly unforeseen.

In the latter part of the book I have attempted to underline the enormous challenges that lie ahead of the new ruling party and its supreme leader, as West Bengal entered a new political era in May 2010. As is usual with any regime change, the teething period in this case too has been prickly and problematic. In fact, in the case of West Bengal, political and governance shifts were decidedly more challenging, more fractious and riddled with both unexpected and expected pitfalls. Mamata has inherited a moribund political and administrative state. The first six months were bound to be critical. The new chief minister was expected to send the right signal not only to her electorate at home, but also to policymakers and the Congress-led UPA government in Delhi.

Two main charges levelled against the Trinamool chief have hinged on the subjects of economic reforms and Maoist insurgency. The recent high-pitched debate triggered by the Centres decision to introduce 51 per cent FDI in multi-brand retail has dramatically brought out into the open the inherent tensions between the ruling Congress and Mamata Banerjee. Mamatas refusal to endorse the opening up of retail has finally forced the government to put the controversial policy on hold. Standing firmly by her partys stated position, Mamata argued that FDI in retail was going to hurt small traders and farmers. Already marked as anti-reform and anti-industry, her hard line against FDI in retail has put her in the direct line of fire of large sections of the political and business classes, as well as the media. At the same time, though the Left will be loath to admit it, Mamata has managedby stalling FDIto play the role it aspires for. She has not shown any indications of turning her back on her partys commitment on issues of economic policy. Her stance has surely evoked disappointment among CPI-M leaders who want her to renege on commitments and desert the constituency that she had weaned away from them. Mamata, however, is not yet ready to give up the Leftist profile she acquired with Singur and Nandigram. In that sense, her stance vis--vis FDI in retail should not come as a surprise to the Congress, which had courted an alliance with the Trinamool leader knowing fully well her stand on contentious issues like this. Paradoxically, with nineteen MPs and as the single largest UFA ally, Mamata has now stepped into the shoes of her Left adversaries.

The other serious allegation against the Trinamool chief, now whipped up with renewed vigour, revolves around her uneasy relationship with the Maoists. Towards the end of November 2011, rising tensions between Mamata and the Maoists led to a major showdown. Following killings of Trinamool workers, Mamata first served an ultimatum to the Maoists, asking them to lay down their arms. Not surprisingly, they refused and demanded that security forces be withdrawn from Jangalmahal. Mamata, however, went ahead and sanctioned a resumption of the security forces operations, even as her critics came down heavily on her and accused her of political expediency. Once perceived as a Maoist ally in her battle against the Left, Mamata was blamed for doing an opportunistic about-turn. Shedding kid gloves, she now seemed ready to deal with the Maoists with an iron hand.

But the debate here is multilayered and complex, going beyond nave and simplistic explanations. During the tribal upsurge in Lalgarh, the CPI-M had launched an acidic campaign, accusing Mamata of aiding and abetting Maoist violence in Jangalmahal. Undoubtedly, her political rhetoric at that time was ambivalent. She did indeed play down the issue in the interest of her ultimate goal of defeating the Left Front government. But to describe Mamata as being hand-in-glove with the insurrectionists would be a gross exaggeration. Her polemical claims aimed at the CPI-Mthat there were no Maoists in Bengalon the eve of assembly elections should not be taken at face value. It was part of the rhetoric of political performance at the time.

Lets not forget that Mamatadespite her recent alliances with Left-leaning intellectuals, artistes and activistshas always been essentially a political centrist at heart. The recent escalation in tension between her and the Maoists needs to be grounded in a context where after assuming power Mamata had given them enough leeway to abandon arms and come to the negotiating table for talks. She had kept the Central and state joint security forces operation in abeyance, which was one of her key manifesto commitments. But the negotiations did not work. Even as the chief minister announced a slew of development packages for Jangalmahal, the Maoists stepped up their offensive. With Mamata sanctioning resumption of security operations against the Maoists, the bonds between her and a sizeable section of Left-leaning intellectuals and human rights activists seem to be on the verge of snapping. The growing distance was manifest when the government-appointed interlocutors, mandated to negotiate with the Maoists, quit following the killing of prominent Maoist leader Koteshwar Rao, popularly known as Kishenji.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Didi: a political biography»

Look at similar books to Didi: a political biography. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Didi: a political biography and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.