Published by

Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2021

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110002

Copyright Bhaswati Mukherjee 2021

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the authors own and the facts are as reported by her which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

ISBN: 978-93-5333-958-6

First impression 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publishers prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

Dedicated to the memory of my parents

Sudhir Krishna Mukherjee

and

Kamala Mukherjee

Born and raised in the syncretic culture of

East Bengal, never to return post 1947

CONTENTS

PREFACE

For last years words belong to last years language,

And next years words await another voice,

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

T.S. Eliot

This is a narrative about partition, the painful division of a beloved part of undivided India, where my family had strong roots for centuriesthe Partition of Bengal. Although in the Indian context, this enforced separation of families and the destruction of their roots is documented against the year 1947, in reality the tragedy unfolded much earlier. It began with the sale of Bengal to the English with Robert Clives farcical victory in Plassey in 1757.

William Dalrymple said: Partition is central to modern identity in the Indian subcontinent, as the Holocaust is to identity among Jews, branded painfully onto the regional consciousness by memories of almost unimaginable violence In a sense, 1947 has yet to come to an end.

Can there ever be closure? Can India and Indians, particularly young Indians, finally move on, leaving this painful national legacy behind them? To attempt to do that, one would have to, like a time traveller, go back to the past and look at history and historical events as they unfolded themselves to the final tragic conclusion. Was this a tragedy waiting to happen, inherent in the demographic and religious fault lines of Bengal? Or, was it a manmade plot, artfully and malevolently conceived by the colonizer, played out amidst scenes of slaughter and violence, whose memories will linger forever?

E.H. Carr in his book, What is History? , had noted: The historian without his facts is rootless and futile; the facts without their historian are dead and meaningless. He then went on to conclude: History is a continuous process of interaction between the historian and his facts, an unending dialogue between the present and the past.

This narrative too shall interpret the facts for a better understanding of our past, even as it throws a long shadow on our future.

E.H. Carr, What is History , Penguin Books 1964, p. 30

BENGAL ENCOUNTERS ISLAM

In a sense, a fact is and cannot be more

sacrosanct than a perception.

E.H. Carr

D id Islam make a violent entrance into Bengal? This is an emotive issue, shrouded in myths and conflicting narratives. Underpinned to each narrative is the unspoken realization that it could justify or reject Bengals partition in 1947. Was there a syncretic culture in Bengal from ancient times? Were the two distinct religious communities living in harmony, bound by a common culture, language, cuisine and racial origin? How did Islam impact Bengal? Did its Eastern wing witness mass and forced conversions to Islam from the Delhi Sultanate onwards, resulting in a significant change in its religious composition?

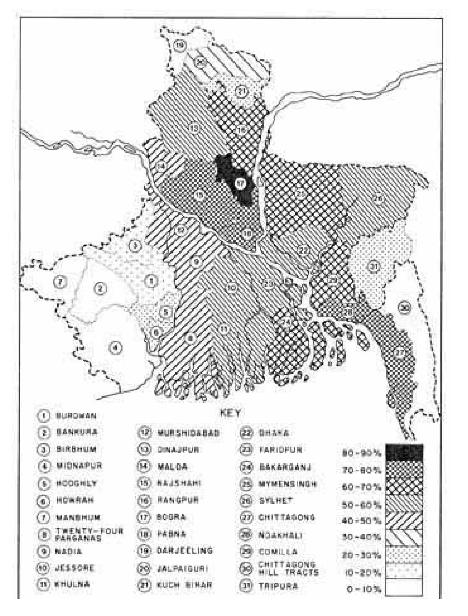

British census figures regarding Muslim population in Bengal are revealing. In the colonial administrations first official census of Bengal in 1872, districts such as Chittagong, Noakhali, Pabna and Rajshahi were shown to have 70 per cent Muslim population. The census was intended to focus on conversions to Islam. The map below demonstrates these figures.

Distribution of Muslim Population in Bengal, 1872

In 1894, commenting on this distribution, British civil surgeon James Wise noted: The most interesting fact revealed by the census of 1872 was the enormous host of Muhammadans resident in Lower Bengalnot massed around the old capitals, but in the alluvial plains of the Delta. He further noted: The history of the spread of the Muhammadan faith in Lower and Eastern Bengal is a subject of such vast importance at the present day as to merit a careful and minute examination.

The census of 1872, followed by the first modern Census of India in 1901, confirmed that Bengals Muslim population was concentrated in the fertile plains, called rice swamps of East Bengal. The Census of India in 1901 acknowledged:

None of these [Eastern] districts contains any of the places famous as the head-quarters of Muhammadan rulers. Dacca was the residence of the Nawab of Bengal for about a hundred years, but it contains a smaller proportion of Muslims than any of the surrounding districts, except Faridpur. Malda and Murshidabad contain the old capitals, which were the centre of Musalman rule for nearly four and a half centuries, and yet the Muslims form a smaller proportion of the population than they do in the adjacent districts of Dinajpur, Rajshahi, and Nadia.

Gaits report: The proportion of Hindus of other castes in these parts of the country is, and always has been, very small. The main castes are the Rajbansis (including Koches) in North Bengal, and the Chandals and other castes of non-Aryan origin in East Bengal.

Gait reasons that it was most unlikely that elite Muslim settlers from North India would have migrated to these areas. Muslim settlers generally sought the higher levels of land near the old capitals. In Gaits words: They would never willingly have taken up their residence in the rice swamps of Noakhali, Bogra and Backergunge.

Gaits conclusions were confirmed by detailed anthropological studies in the period leading up to 1947. It was accepted that the Bengali Muslims concentrated in the rural areas of East Bengal were not outsiders but were converts from lowest caste Hindus.

In an important study in 1938 of the 24 Parganas District, Eileen Macfarlane concluded: The blood-group data of the Muhammadans of Budge Budge show clearly that these peoples are descended from lower caste Hindu converts, as held by local traditions, and the proportion remains almost the same as among their present-day Hindu neighbours.

In 1941, a study by B.K. Chatterji and A.K. Mitra came to the same conclusion with regard to the 24 Parghanas District.

In 1960, a third authoritative study by D.N. Majumdar and C.R. Rao, using the same data indicators collected in 1945, two years before the partition, came to a similar stark and clear conclusion.