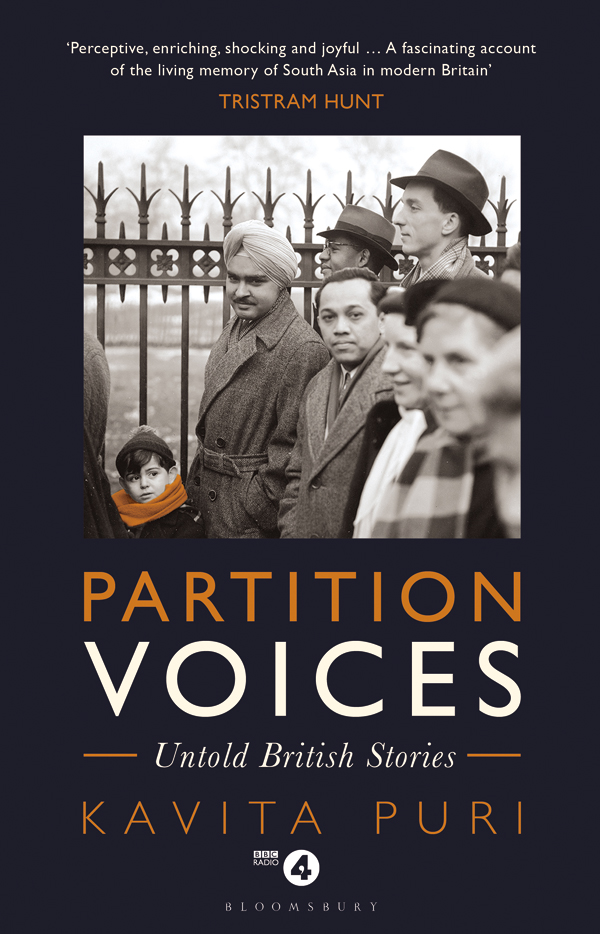

Kavita Puri - Partition Voices: Untold British Stories

Here you can read online Kavita Puri - Partition Voices: Untold British Stories full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Partition Voices: Untold British Stories

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Partition Voices: Untold British Stories: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Partition Voices: Untold British Stories" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Partition Voices: Untold British Stories — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Partition Voices: Untold British Stories" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PARTITION VOICES

BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2019

This electronic edition published 2019

Copyright Kavita Puri, 2019

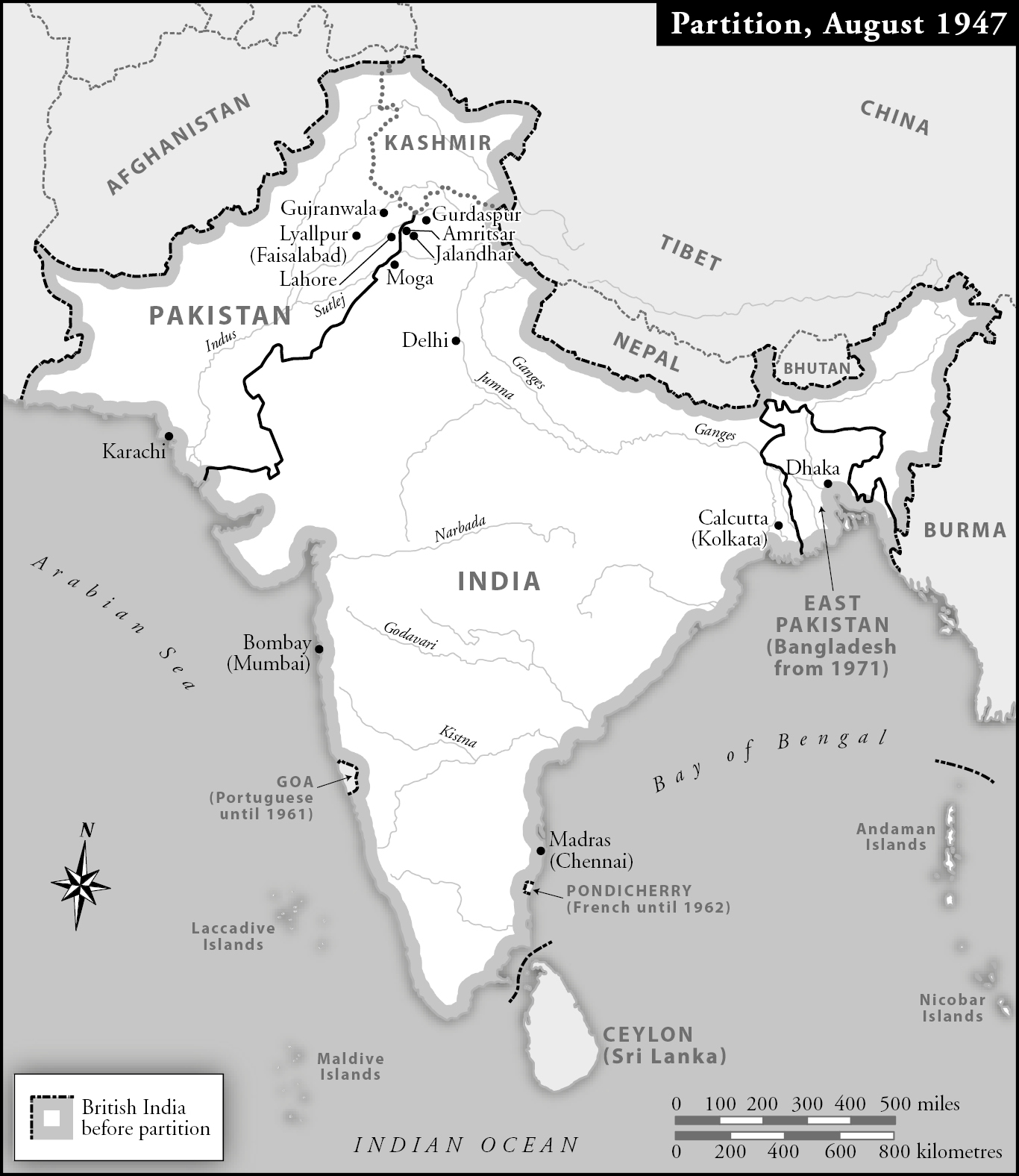

Map ML Design, 2019

By arrangement with the BBC. The BBC logo is a trademark of the British Broadcasting Corporation and is used under licence. BBC logo BBC 1996.

Kavita Puri has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for

ISBN: HB: 978-1-4088-9907-6; TPB: 978-1-4088-9908-3; EBOOK: 978-1-4088-9906-9

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

For my father

and my girls

Contents

The place where heaven meets earth is the River Ganges. Ma Ganges.

It is the place we carried my father on his final journey.

He requested his ashes to be taken to the sacred place of Haridwar, where his siblings, parents and ancestors before him had been scattered. It is where the Ganges enters North India for the first time, and is one of the holiest places in Hinduism.

We took him to a peaceful corner of the river, our small group settling together on the ghat , a flight of steps leading down to the waters. A priest was found. A shaven-headed man in his saffron robes laid down a blue embroidered carpet for us to sit cross-legged on and in practised fashion took my fathers ashes out of the urn onto a stainless-steel plate. To be confronted with your parent in such a stark way face to face with their remains is difficult and surreal. It is what the physical life is reduced to for observant Hindus like my father. Before me, it was not the texture of ashes as I expected but small grey granules of what must have been his bones.

My father had been cremated near his home in Kent in his favourite suit and shoes, along with fresh rose petals, camphor, ghee and tulsi leaves, which we had sprinkled on his body during the final rites. The last thing we had done before we closed the casket was to place a picture in it, drawn days earlier by my younger daughter. I wondered where that drawing covered in hearts was in my fathers remains in front of me, on that cold stainless-steel plate.

The priest began his Sanskrit prayers. Following his instructions, at intervals, we threw marigolds and rose petals on the ashes, while the priest sprinkled holy Ganges water. When the time came, my sister and I took the plate and ashes, which were now almost covered by flowers, to the rivers edge, where the waters lapped our bare feet, as we held our father for the last time.

The priest gave the final prayer as we stood:

Om Asatho Maa Sad Gamaya.

Thamaso Maa Jyotir Gamaya.

Mrithyur Maa Amritham Gamaya.

Om Shanti, Shanti, Shanti.

From untruth lead us to Truth.

From darkness lead us to Light.

From death lead us to Immortality.

Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

Holding each side of the plate, my sister and I gently tipped it towards the river, allowing my fathers ashes to slowly descend into the waters, the waters which had carried his forefathers ashes. We watched as his remains swirled in the Ganges, drifting away from us.

Gradually, our small group returned to the steps. As we sat down it was still possible to differentiate his ashes from the waters. My aunt sang an Indian bhajan , a devotional song, Tare Nahi Tare. What Has to Happen Has to Happen.

We sat in silence as the sun began to set. The light was starting to grow hazy and the first pink of the sky was emerging. Another family next to us were committing a loved one to the waters. On the opposite bank an elderly woman in a fuchsia-coloured sari had been sitting statue-like, watching the waters all the time we had been there. I looked carefully to check she was real. A young boy, his trousers hitched to his waist, was knee-deep in the river, panning for metals, hoping no doubt to make some quick money. And my father, his remains now disappeared from view, finally in the place he wanted to be, where sins are cleansed and Hindus believe immortality is to be found.

Born in Lahore, Pakistan, an adult life lived in England, he now rests somewhere along the most sacred and blessed river in India.

My father broke his silence after nearly seventy years to speak about what happened to him during the partition of British India. Seventy years. A lifetime. He never returned to the place of his birth, the place he was forced to leave, the place he always hoped to see again.

Ravi Datt Puri was born in 1935 in Lahore, Punjab, in British Colonial India. When he finally told me about the things he had witnessed as a twelve-year-old boy, I understood why he had kept his silence.

The division of British India in August 1947 along religious lines into the independent states of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan sparked the largest mass migration outside war and famine the world has ever seen. In the months around partition, at least 10 million people were on the move: Muslims to West and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), and Hindus and Sikhs in the opposite direction. It was accompanied by unimaginable violence on all sides.

The human cost of dividing British India was staggering. Up to a million people were killed in communal fighting and tens of thousands of women raped and abducted. The statistics are hard to comprehend, and yet behind every single number is a story. It is one of centuries of coexistence shattered, homes left hurriedly, painful goodbyes, epic journeys and traumatic loss. Not just loss of a house or possessions but a loss more profound. Loss of a homeland. This grief is still tangible seventy years on.

For centuries, across the Indian subcontinent, Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs had lived together largely peacefully with shared traditions and culture, observing each others religious festivals. Ties to land could be stronger than ties to religion. Of course there were differences: there was no intermarriage; most Hindus did not eat at the homes of Muslims; there were socio-economic disparities and cases of localised outbreaks of communal trouble. But mostly, these people of different faiths had lived together, side by side, for generations.

However, religious identity in the decades leading up to partition was becoming stronger. Many argue that it was stoked by the British policies of divide and rule. There were two visions of independence emerging and they were becoming politicised along religious lines. The Congress Party led by Jawaharlal Nehru wanted India to remain united after the British left. By 1940, the leader of the Muslim League, Mohammed Ali Jinnah (formerly a member of the Congress Party) was bitterly at odds with Nehru. He felt Indias almost 100 million Muslims, a quarter of the population, would be marginalised by the Hindu majority in an independent India. He demanded safeguards even a separate homeland for Indias Muslims.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Partition Voices: Untold British Stories»

Look at similar books to Partition Voices: Untold British Stories. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Partition Voices: Untold British Stories and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.