URVASHI BUTALIA

THE OTHER SIDE

OF SILENCE

Voices from the Partition of India

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE OTHER SIDE OF SILENCE

Urvashi Butalia is a renowned writer and the publisher of Zubaan, a feminist publishing house. She has been active in the womens and civil rights movements in India, and writes on issues relating to women, media, communications and communalism. She is the editor of Partition: The Long Shadow , and the co-editor of Women and the Hindu Right: A Collection of Essays and In Other Words: New Writing by Women in India . She is the recipient of the French Chevalier des Artes et des Lettres, the Nikkei Asia Prize and the Padma Shri from the Indian government. She was awarded the prestigious Goethe Medal in 2017.

Praise for

THE OTHER SIDE OF SILENCE

WINNER OF THE ORAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION BOOK AWARD IN 2001 WINNER OF THE NIKKEI ASIA PRIZE FOR CULTURE IN 2003

The Other Side of Silence is without a doubt one of the most important books ever to be written about the Partition of the Indian subcontinent. More than a history, more than a memoir, it is also an extended reflection on narrative form. Official history has always flinched from acknowledging the full extent of the human cost of Partition. Urvashi Butalia shows us why we cannot afford to forget the suffering, the grief, the pain and the bewilderment that resulted from the division of the subcontinent. [This] is an extraordinary achievementAmitav Ghosh

Urvashi Butalias The Other Side of Silence is a groundbreaking account of Partition that gives primacy to the voices of the people, particularly the women, who suffered in the great convulsions of cruelty and revenge. Anyone who wants to understand the foundations of modern India should read itIan Jack

Selective amnesia and memory are at the root of the relationship between human beings and their history. This book pierces that amnesia, elicits buried memories, and lays the foundations for a more evolved relationship between human beings on this subcontinent and their histories of gendered and communal violence Telegraph

This is a magnificent and necessary book, rigorous and compassionate, thought-provoking and moving. Oral history at its bestSalman Rushdie

These shaming historiesso long under wrapsare narrated with honesty and clarity and informed by compassionBapsi Sidhwa

A brave, moving and troubling book that voices, for the first time, dark truths about our historySunil Khilnani

[This] extraordinary book is testament that words can evoke an unbearable degree of pain, memories, anguish and lost worlds.... The silence that surrounds Partition has always been unnoticed because of the deafening discourses that have sought to explain and recuperate the coming to be of the nation(s). Butalias work, among its many accomplishments, reminds us that all too much of our attention has been focused on that which is spoken or writtenat the cost of ignoring the immense ocean of meaning that constitutes our silences Theory and Event

Outcome of a decade long research based on interviews with survivors of the partition, Urvashi Butalias book recaptures in all its intensity the schizophrenic crisis which still haunts these survivors, mostly in their private moments, but also spilling out in public interviews Economic and Political Weekly

A book every thinking Indian should read Biblio

For my mother Subhadra

And my father Joginder

Who taught me about Partition

For Ranamama, my uncle

Who lives the Partition from day to day

And for my grandmother Dayawanti/Ayesha

Whose life Partition shaped

As it did her death

Return

It is twenty years since this book was published and many more since I researched and wrote it. It is both difficult, and challenging, to return to something after such a long time. Everything is different: the person you were when you wrote the work, the context in which it was thought about and written, the viewpoint from which you are looking at it today. If you, as author, are different, so too is the external environment in which the work took root and shape. So much has changed in twenty years: if in the India of two decades ago the fault lines of our nation state were beginning to become visible, today the divisions are full-blown and growing. If people of my generation grew up in what could broadly be defined as a secular India, today the divisive power of religious majoritarianism is all around us and pressing inwards, hemming us into identities we have never wished to own. In the newly independent India in which I grew up, words like nationalism and patriotism did not have the sinister meanings they do today.

When I wrote this book twenty years ago, like many others in India, I was deeply concerned at what we saw as the rise of religion-based identity politics and the ways in which it was playing on imagined fears. Today, that moment seems almost as if it was a setting of the stage for a politics of upper caste, majoritarian domination. With a right-wing, statedly Hindu government in power, one that wants to restore India to an imagined former glory, these fears are no longer just fears, they are no longer just imagined; they are very real, and indeed very violently enacted, with minorities and people at the bottom of the caste ladder being the most vulnerable. The ghosts of Partition are here to haunt us again, and perhaps to alert us once again to the need to more closely examine the many aspects of its history.

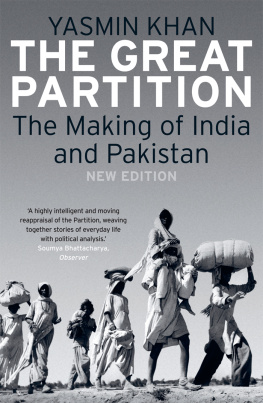

Perhaps this is why, in the last two decades, the need to understand more deeply the euphoric, hopeful and simultaneously violent and bloody moment of the birth of the nation has intensified and gathered momentum. New histories have been written, new subjects uncovered, new controversies raised, new questions asked. Many of these offer exciting new possibilities for research, and some are also matters of concern. In the new Hindu resurgent India, for example, spaces have opened up for the articulation of narratives of Hindu victimhood and hurt during Partition that are increasingly legitimized and presented as truth , and are almost coercively and loudly validated by the power of the majority, sometimes even that of the State, and at other times that of street-level actors.

This year, it is seventy years since India became independent and was simultaneously divided. The tragic reality is that the divisionempires answer to what our colonial rulers saw as the intractable problem of the peaceful coexistence of people of different religions and communitiesleft behind a legacy of bitterness and enmity that ensures blind hatred, terrible prejudice and deep ignorance, which we are still dealing with today. This legacy manifests itself differently in different places. In Punjab much of the hatred and bitterness is directed at people across the border in Pakistan, partly because the post-Partition scenario left behind an Indian Punjab which was largely devoid of its Muslim population. In Kashmir the struggles were different, around ideas of belonging and independence, of Hindu and Muslim identities and notions of Kashmiriyat and more recently on the role of a coercive State, but this also referenced a history from across the border. In Bengal, both East and West, the issues centred on migration from East Pakistan and later Bangladesh, but also previous migrations from what was East Bengal to Assam, and then the influx of refugees post Partition, and after 1971; over the long history, these migrations involved both Hindus and Muslims.