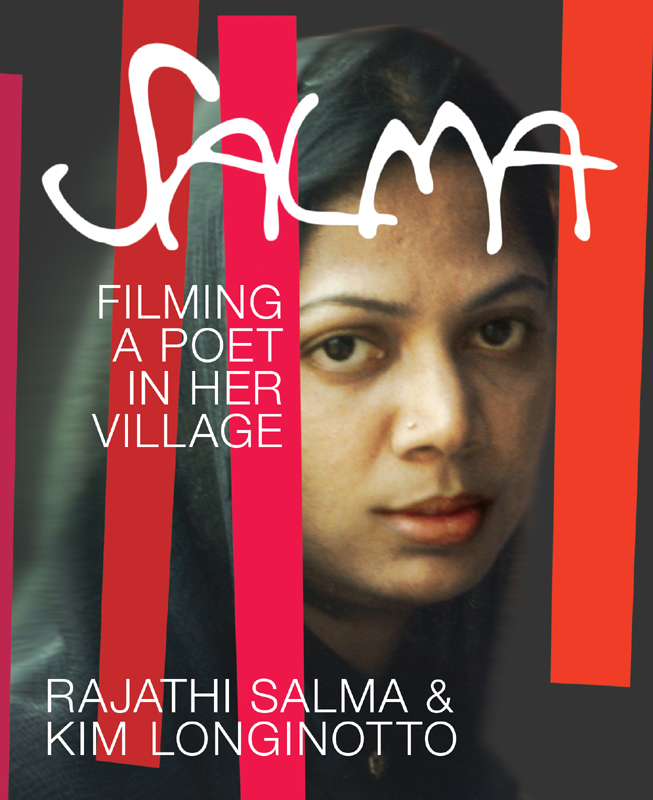

2013 Rajathi Salma and Kim Longinotto

Translation of all poems 2013 N. Kalyan Raman except for Breathing and New Bride, New Night 2013 Hari Rajaledchumy

Published by OR Books, New York and London

Visit our website at www.orbooks.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

First printing 2013

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-939293-13-8 paperback

ISBN 978-1-939293-14-5 e-book

Typeset by Lapiz Digital, Chennai, India.

DREAMS AND WRITING

My youth was full of dreams and their fragrances. Those days, bereft of contact with outsiders, forbidden as if it were the fruit of Adam and Eve, I spent in conversation with books and with myself. It was a period when the dark, wearisome, and inert hours of the daytime made me yearn daily for nightfall. The night was a time of sleep, and sleep was the pathway to dreams. With every night beginning and ending with dreams, my days began to grow heavy. Just like the protagonists of my novel, I too had a life that was made up of journeys in the night. Later, when it was clear that my dreams were to go unfulfilled, my days began to char and blacken. An innocent girl forsaken by fortune and the gods, I was forced onto a circular path. In that situation, the solitary hope that I clung to was to be found in books and writing.

At the time I scarcely knew the other door which was about to open nor anything of its limitless boundaries. The darkness, rancor, and the pain of not being able to write were escaped through that door, an d from then on my world was surrounded by light. I pinch myself to ascertain that the path I am walking on is indeed real.

Today, those dreams of an earlier time are gone; so is my youth; so is the Salma of those bygone years. I am no longer afflicted by the pain of not being able to write. The pages yet to be written, the distance yet to be traversed, and a life that is happy to some degreeall these are solely in my hands. I must spend this life writing with energy and commitment.

Just as books had broadened my perspective then, Kim Longinottos documentary Salma has expanded my world today. By editing and publishing this book, Colin Robinson has tried to give a certain fillip to my writing.

Salma, July 2013

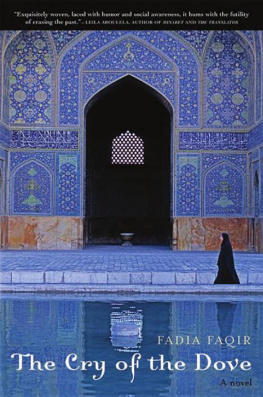

In the village. From left to right: Amina, Salmas grandmother; Fatima, Salmas niece; Salma; Salmas mother, Sharbunnisha

In the village. From left to right: Amina, Salmas grandmother; Fatima, Salmas niece; Salma; Salmas mother, Sharbunnisha

FILMING SALMA

Kim Longinotto

In January 2011, I was in Delhi showing my film Pink Saris . The festival was held at the India International Center and the screening was outside at night, under a half moon, in the lovely gardens there. During a seminar the following day, Urvashi Butalia, head of the Indian feminist publishing company Zubaan Books, proudly told a group of us about a Tamil writer and poet, Salma, who shed recently published. Salmas story was so inspiring and unusual that I knew I wanted to make a film with her.

Salma grew up in a village in Tamil Nadu, South India. When she was born, her father was very disappointed to have another daughter. He already had three girls from his first wife and now his new wife, Salmas mother, had failed to give him a boy. So Salma was handed over immediately to her aunt who was just a child herself, only seven years old.

As soon as Salmas aunt reached puberty, she was married off and so Salma had to go back to live with her parents. Salma loved school and having friends but in keeping with village tradition she was forced to leave school when she was just thirteen years old. She was kept inside her family home, often restricted to a tiny room, for nine years, until she agreed to marry. After the marriage, Salmas husband still refused to let her go outside and she spent a further fifteen years kept inside except for occasional visits to her mothers house. During this time Salma became a devoted reader and then started writing herself, composing poems that are raw and eloquent expressions of her experience of seclusion.

Using an elaborate system of subterfuge, and with her mothers help, Salmas poems were smuggled out of her home and eventually found their way to Kannan Sundaram, a publisher in Nagercoil, who, recognizing their power and originality, printed them in his magazine. They caused a sensation. No one had ever read Tamil poems like these, composed with such passion, and from a womans point of view. They were so beautifully written that people imagined they must have been penned by an educated city dweller, man or woman, and written in the persona of a village girl. There was great speculation as to who this Salma might be.

ONE EVENING

Another evening

slips withered

into the crevice of loneliness.

Legs too weak

to scale the walls

walk about in the dark

of the inner chambers.

In the heat of breaths

exhaled by the rooms

neat arrangements rises

the pungent odour of sulphur.

There can be no second opinion

on the futility of the attempt

to excavate and thaw

dreams long frozen.

There could be species

in this universe that live

in pleasure, subsisting only on

their prey and conjugal courtesies.

The succession of tense nights

and the childs restless whines

will turn into

a source of mockery about me.

This existence

is complicated

like the life of a cat

that hides in the kitchen.

A thick layer of cream has formed

on the tea waiting to be drunk;

its burnt smell is hounding me.

In the drawing rooms

full of human bustle,

theres no one with whom

I might strike up an acquaintance.

Solitude in the bathroom

creates fear, stemming from

revulsion over nudity.

Houses erected inside cages

swell their hustle and bustle

solely to frighten me.

In the gardens raised

within walls, theres no shade

in which to sit and rest.

Nor is privacy ensured

by the open spaces

of the terrace upstairs.

Theres no seat on which

to sit comfortably,

dangling ones feet.

If my child

loaned me

his crib,

sleep might become possible.

Finally a Chennai journalist, Arul Ezhilan, managed to track Salma down in her village and persuaded her to let him take a quick photograph. Her picture appeared in his magazine and the mysterious Salma was suddenly unmasked as a village woman who had hardly ever been outside her home. The village was scandalized and Salmas life was very, very difficult and dangerous for a long while. Salmas husband, Malik, was the head of the village at the time and, though he himself was hostile to her writing, his powerful position in the village probably afforded her some protection.

The next elections for Maliks position as Panchayat Leader came under a special government edict that only women be allowed to apply for the job that year. Malik tried to persuade several women in his family to run as a surrogate for him, but they all refused. Then, in desperation, and at the last minute, he asked Salma. She signed the form and her life was transformed. Her mother-in-law suddenly had to allow her to go out to campaign. Salma could also argue that she would never win votes if her face was hidden from view.

Next page

In the village. From left to right: Amina, Salmas grandmother; Fatima, Salmas niece; Salma; Salmas mother, Sharbunnisha

In the village. From left to right: Amina, Salmas grandmother; Fatima, Salmas niece; Salma; Salmas mother, Sharbunnisha