For my father, Mir Mahhooh Ali,whose voice I always hear reciting poetry to me.

For my father, Mir Mahhooh Ali,whose voice I always hear reciting poetry to me. Mir Mafhuz Ali

Mir Mafhuz Ali  Seren is the book imprint of Poetry Wales Press Ltd. 57 Nolton Street, Bridgend,Wales, CF31 3AE www.serenbooks.com facebook.com/SerenBooks The right of Mir Mahfuz Ali to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Mir Mahfuz Ali 2014 ISBN: 978-1-78172-159-9 e-book: 978-1-78172-160-5 Kindle: 978-1-78172-161-2 A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. The publisher acknowledges the financial assistance of the Welsh Books Council.

Seren is the book imprint of Poetry Wales Press Ltd. 57 Nolton Street, Bridgend,Wales, CF31 3AE www.serenbooks.com facebook.com/SerenBooks The right of Mir Mahfuz Ali to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Mir Mahfuz Ali 2014 ISBN: 978-1-78172-159-9 e-book: 978-1-78172-160-5 Kindle: 978-1-78172-161-2 A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. The publisher acknowledges the financial assistance of the Welsh Books Council.

Book Cover Design: Khandaker Enamul Haque Artist: Aniruddha Kar Printed in Bembo by Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow Author website: www.mirmahfuzali.com Midnight, Dhaka, 25 March 1971 I am a hardened camera clicking at midnight. I have caught it all the screeching tanks pounding the city under the massy heat, searchlights dicing the streets like bayonets. Kalashnikovs mowing down rickshaw pullers, vendor sellers, beggars on the pavements. I click on, despite the dry and bitter dust scratched on the lake-black water of my Nikon eye, at a Bedford truck waiting by the roadside, at two soldiers holding the dead by their hands and legs, throwing them into the back, hurling them one upon another until the floor is loaded to the skys armpits. The corpses stare at our stars succulent whiteness with their arms flung out as if to bridge a nation. Their bodies shake when the lorry chugs.

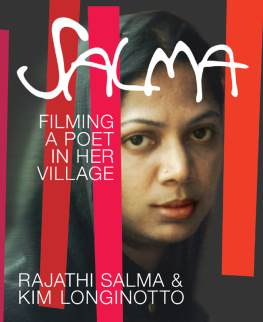

I click as the soldiers laugh at the billboard on the bulkhead: GUINNESS IS GOOD FOR YOU SIX MILLION DRUNK EVERY DAY. My Salma Forgive me badho, my camellia bush, when you are full of yourself and blooming, you may ask why, having spent so many years comfortably in your breasts, I still dream of Salmas, just as I did when I was a hungry boy in shorts, her perfect fullness amongst chestnut leaves. The long grass broke as I ran, leaving its pollen on my bare legs. When the soldiers came, even the wind at my heels began to worship Salmas beauty. * A soldier kicked me in the ribs. I fell to the ground wailing.

They brought Salma into the yard, asked me to watch how they would explode a bullet into her. But I turned my head away as they ripped her begooni blouse, exposing her startled flesh. The young soldier held my head, twisting it back towards her, urging me to spit at a woman as I might spit a melon seed into the olive dirt. * The soldier decorated with two silver bars and two half-inch stripes was the first to drop his ironed khaki trousers and dive on top of Salma. His back arched as she fought for the last leaf of her dignity. He laughed as he pumped his rifle-blue buttocks in the Hemonti sun.

Then covered in Bengals soft soil, he offered her to the next soldier in line. They all had their share of her, dragged her away out of the yard. I went in search of Salma, among the firewood in the jungle. * I stood in the middle of a boot-bruised field, working out how the wind might lead me to her. Then I saw against the deepening sky a thin mangey bitch, tearing at a body with no head, breasts cut off in a fine lament. I knew then who she was, and kicked the bitch in the ribs, the same way that I had been booted in the chest.

Hurricane A storm roared over the Bay of Bengal, a glass bull, charging with its horns. It pounded throughout the long night as we children huddled together inside our fatherless bungalow. We watched our tin roof rip off. First from its tie beams then the ceiling joists. One by one the rest of the house vanished as we covered our heads with our hands and saw our possessions take flight The Koran, War and Peace, Gitanjali, the clothes in the alna, shoes and sandals, sisters dolls and brothers cricket bats. We children couldnt understand what sins wed committed, but we asked Gods forgiveness.

We thought the worst was over. Then came the giant waves one after the other snatching us from the arms of our mother, tossing us like cheap wood. Trees fell, exposing their great roots. Cats and cattle lay dead on the ground. Our bodies shrivelled with water, shuddered like old engines. Teeth rattled to the point of rapture.

The sun came very late that day, found us trapped in a wind-sheared tree. We couldnt hear the birds singing or the muezzin calling for prayer. Silence, the new disease, swept across our land. Our Boowah Our housemaid is a tiny woman with a lanky grey body. Her face is round, eyes amber, slight limbs are dark and yet sweet like raisins. She wears no lavender powder or brightly-coloured lipstick unless there is a party.

Her constant laughter tells you she was once a langur who leapt and made the tree tops quiver with her monkey wish. This woman thinks she is still in the Garo Hills, crouching behind a lantana bush and free to do whatever she likes with us children. This is the woman who fed me bananas and peanuts with her hand, let me hang from her neck, ride on her slim back. She lulled me to sleep with her strange songs, tapped my back and taught me not to have nightmares. Nandita Someone could have told me you have to rot before you ripen days of open fields and running free, of ruining my shirt by going into the sugar-canes with the Hindu girl Nandita, showing her the language of the bush in the mist-flavoured twilight. The lilt of her sari roused the leaves we needed for our art.

A hot tincture in her blouse drove me to be with her mouth. At first, she turned me away then she washed me in that blue rustling hedge while the country slid inside her shitala quilt. Many times we hid under the little candle of the iced moon, senses tingling to the last drop of dawn. Cord Ask the bimal bamboo that carries my name in its long slender canes. It will tell you I belong here among the jaruls and jamruls by the clay-pond banks at the back of the house where I was born many harvests ago. I am not a stranger to the boatman, Kadam Ali, or the village poet, Folo Bibi, and her roaming ally, Bawool Srimathi.

They might have told you how I pierced the pitchers on girls heads with my sling shots, soaking their kortas and kamizes. But you should have heard how I played naked in the monsoon mud with Saima Nanda. I am not a stranger to the smell of the earth. Many times I helped Jabor Ullah plough the hard land softened by morning mist. I saw how he sniffed the odour of the earth cradled in his hands, pushed me to understand the thick richness of cow dung. I am not a stranger to the willows melt through the water, rippling the dinghys sleep.

If you care to roll your eyes on what I have done before I began a runaway life. I am not an outsider, though I am travelling through this field, and a river journeying through me, is carrying the silt of every memory. While I am thatching a roof or building up a hay-sack. My umbilical cord is buried under that orange tree in June. Jonaki O firefly! You have come out of the hedgebank shadow. But your flickering flight cannot drive back the dark.

You neither have the suns fire nor the moons ice.Your white lantern blinks on and off, wants to sleep and dream the life of trees which burrow their roots into the wet to terrify the worms. If the trees could babble, theyd only hum some low green note for the lonely place where ripe fruits wake the birds. My First Shock at School Muktar was his name his tongue still white with his mothers milk and he sucked his thumb in the classroom. Monsoon music drowned the day. Our Lakeside School was surrounded by black waters. Water-hyacinth, rice-grass and lotus covered the lake.

Next page

For my father, Mir Mahhooh Ali,whose voice I always hear reciting poetry to me.

For my father, Mir Mahhooh Ali,whose voice I always hear reciting poetry to me. Mir Mafhuz Ali

Mir Mafhuz Ali  Seren is the book imprint of Poetry Wales Press Ltd. 57 Nolton Street, Bridgend,Wales, CF31 3AE www.serenbooks.com facebook.com/SerenBooks The right of Mir Mahfuz Ali to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Mir Mahfuz Ali 2014 ISBN: 978-1-78172-159-9 e-book: 978-1-78172-160-5 Kindle: 978-1-78172-161-2 A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. The publisher acknowledges the financial assistance of the Welsh Books Council.

Seren is the book imprint of Poetry Wales Press Ltd. 57 Nolton Street, Bridgend,Wales, CF31 3AE www.serenbooks.com facebook.com/SerenBooks The right of Mir Mahfuz Ali to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Mir Mahfuz Ali 2014 ISBN: 978-1-78172-159-9 e-book: 978-1-78172-160-5 Kindle: 978-1-78172-161-2 A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. The publisher acknowledges the financial assistance of the Welsh Books Council.