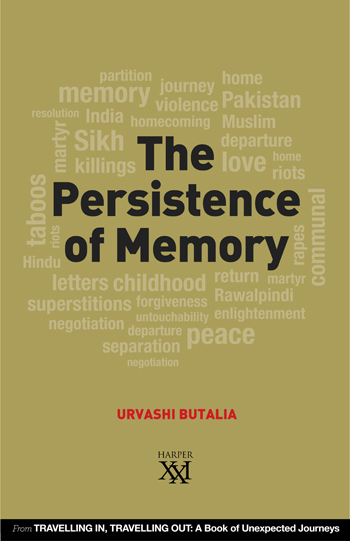

Urvashi Butalia - The Persistence of Memory

Here you can read online Urvashi Butalia - The Persistence of Memory full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: HarperCollins Publishers India, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Persistence of Memory

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins Publishers India

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Persistence of Memory: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Persistence of Memory" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Persistence of Memory — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Persistence of Memory" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE PERSISTENCE OF MEMORY

URVASHI BUTALIA

Table of Contents

URVASHI BUTALIA

On 11 March 1947, Sant Raja Singh of Thoa Khalsa village in Rawalpindi district picked up his sword, said a short prayer to Guru Nanak, and then, with one swift stroke, tried to bring it down on the neck of his young daughter, Maan Kaur. As the story is told, at first he didnt succeed: the blow wasnt strong enough, or something came in the way. Then his daughter, aged sixteen, came once again and knelt before her father, removed her thick plait, and offered him her neck. This time, his sword found its mark. Bir Bahadur Singh, his son of eleven, stood by his side and watched. Years later, he recounted this story to me: I stood there, right next to him, clutching on to his kurta as children do ... I was clinging to him, sobbing, and her head rolled off and fell... there ... far away.

Shortly after this incident, Bir Bahadurs family fled Thoa Khalsa, heading towards the Indian border where they hoped to find safety. India was being partitioned, and large-scale carnage, arson, rape and loot among Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs had become the order of the day. In many families, like Bir Bahadurs, the men decided to kill the women and children, fearing that they would be abducted, raped, converted, impregnated, polluted by men of the other religionin this case Muslims. They called these killings the martyrdom of women.

It was only two years earlier, in 1945, that Bir Bahadurs family had moved to Thoa Khalsa. Talk of a possible partition was in the air and they were worried for their safety. Saintha, the village in which they had lived for many years, was a Muslim-majority village and theirs was the only non-Muslim family there. It was this that had made Bir Bahadurs father, Sant Raja Singh, decide to move to Thoa Khalsa, where there were many more Sikhs than Muslims. Everywhere, at this time, people banded together with their own kind, believing that safety lay in numbers. Ironically, and tragically, it was in Thoa Khalsa that the real violence took place. In retaliation for attacks by Hindus and Sikhs on Muslims elsewhere in India, villages in this part of Rawalpindiinhabited mainly by Sikhs came under concerted attack for several days. Shortly after Sant Raja Singh killed his daughter and several others, he asked a relative to take his lifeperhaps the burden of what he had done was too heavy to bear. A single shot from a gun ensured that he joined the ranks of the martyrs.

Forty years later, Bir Bahadur told me these stories. I had met him while researching a book on oral histories on the partition of India. In the lower-middle-class area of Delhi where he lived, Bir Bahadur was someone people looked up tohe came from a family of martyrs. Not only his sister, but several other women had been killed on that day. Bir Bahadur had been a young boy at the time, but his memories were crystal clear and sharp. He remembered the fear and the violence and remembered too that when the attacks had begun to seem imminent, people from his home village of Saintha had come to Thoa in a delegation to offer his family protection. They were led by Sajawal Khan, the village headman. But his father had turned them away. They were Muslims and, even though he had lived among them in safety and peace for many years, he no longer trusted them. Bir Bahadur has never forgotten this rejection.

Stories of such violenceand moreare routine when Muslims and Hindus speak of the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. The British decision to partition the country into two, India and Pakistan, led to the displacement of millions of people, a million deaths, and nearly a hundred thousand incidents of rape and abduction. Women were particularly vulnerable: not only was there mass rape and abduction but hundreds were killed by their own families, ostensibly as a from of protection, some had their breasts cut off, others had symbols of the other religion tattooed on their bodies. But while stories of violence are routine, what is less known are the stories of friendship that cut across the rigid borders drawn by the Indian and Pakistani states. In the year 2000 Bir Bahadur and I embarked on one such journey of reconciliation across what had till then seemed like a somewhat intractable border.

It all began with a phone call from Chihiro, a Japanese journalist. She was keen to make a programme featuring an Indian travelling to Pakistan on the India-Pakistan bus, visiting his/her relatives. She, and a crew, would travel along with this person and film the journey as well as the homecoming. She asked for suggestions. I offered Bir Bahadurs name. For years he had wanted to go back to his village in Pakistan, but had never had the opportunity. Now it had presented itself.

Today in his seventies, Bir Bahadur Singh is a tall, statuesque Sikh with a white, flowing beard. Always dressed in white, with a black turban and a saffron head cloth showing through, he makes an arresting figure. His family was only one among the millions of refugees who fled from Pakistan to India. They carried nothing with them and Bir Bahadurs key memories of that time are of hunger, fear and cold. Once in India, Bir Bahadur and his family struggled to keep body and soul together. He tried his hand at different things and then, at eighteen, managed to put together enough to set up a small provision store. Later, his family arranged for him to marry a woman from a village close to his home in Rawalpindi, and together they brought up a large family. Bir Bahadur has never been rich, and he has worked hard all his life for the sake of his children. A might-have-been politician (he stood for municipal elections on a Bharatiya Janata Party ticket some years ago and lost), he now leads a retired life, dividing his time between his farmhouse close to Delhi, his extended family of children and grandchildren, and his old (ninety plus) mother who lives close by. He was beside himself with excitement at the news that he might get permission to travel to Pakistan and visit his home village.

With Japanese intervention visas were swiftly arranged and a few days later, we left for Pakistan. Bir Bahadur arrived at my house with a small bag and a sackful of hard, dry coconuts. These were to be his offerings to the people of his village. There are no coconuts there, he explained, and the people love them. He had also written two letters, one to the people of his village, and one to his school friend, Sadq Khan, son of Sajawal Khan. We were good friends in school, he said, I am sure he will remember me. These he carried with him, in the event that we did not make it to the village. He was convinced we would find someone, somewhere, who would carry his letters to the village, and people from there would arrive in immediate response, to see him. For days hed been like a child, excited and nervous. Hed ring me up every daysometimes twice or three times in a dayto check on this or that detail. Would we be staying in a hotel? How much money should he bring? Could we not persuade Chihiro to do a radio programme instead of one for television (we did)it would be much less obvious. And now that we were actually on our way, he could not believe his luck.

Heavy rain had delayed the flight. We spent a long and tiring night waiting at Lahore airport, uncomfortable in plastic seats. Occasionally, Chihiro and I would doze off out of sheer exhaustion. But not Bir Bahadur. Every time I opened my eyes, he would be wide awake, sitting on his haunches in the airport chairs, recounting his story to someone or the othernow a family on their way to Karachi (also delayed), now two helpful employees of the airport (with whom he was quickly exchanging photographs and addresses) and now the toyshop owner or the man selling tea...

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Persistence of Memory»

Look at similar books to The Persistence of Memory. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Persistence of Memory and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.