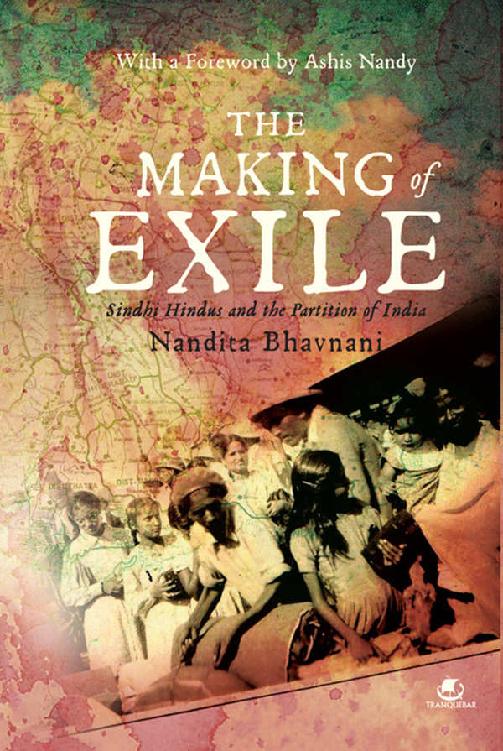

TRANQUEBAR PRESS

61, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600 095

No. 38/10 (New No.5), Raghava Nagar, New Timber Yard Layout, Bangalore 560 026

93, 1st Floor, Sham Lal Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002

First published in India in Tranquebar Press by westland ltd, 2014

First e-book edition: 2014

Copyright Nandita Bhavnani 2014

The copyright for the excerpts rests with the individual authors, their heirs and trusts. While every effort has been made to obtain permission to use material from other sources, any omission brought to the notice of the publisher will be rectified in future editions of the book.

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-93-84030-33-9

Typeset in Aldine401 BT by SRYA, New Delhi

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, circulated, and no reproduction in any form, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews) may be made without written permission of the publishers.

For my parents,

Nirmala and Nari Bhavnani

Contents

Introduction

I cannot remember when I first became aware of Partition. Perhaps I had known from an early age that, as Sindhis, both my parents had been born in another, inaccessible land, where they had spent their childhood years. I cannot remember when they first told me about it. They never actually spoke about Partition specifically. My mother would speak to my sister and me, once in a while, of her life in Sindh. She would describe her comfortable Karachi home and neighbourhood, and mention this or that incident from her childhood. She would tell us of the novelty of visiting her mothers family in Hyderabad, and of the mouth-watering street food that she and her cousins would buy for the absurd price of four pice . Occasionally, she would refer to the difficulties that she and her family faced in the early years in India: of how she was separated from her parents for a while when she was sent to Calcutta to live with her eldest brother and sister-in-law; of the familys straitened circumstances; of how she, as the youngest child, was made to sleep on top of the dining table in her married sisters small flat in Bombay, which had been flooded with relatives after Partition; of her beloved collection of books that she was forced to leave behind in Karachi. So, without our being told specifically about it, the fact of Partition was very much a part of our family background, something that my sister and I took for granted but actually knew very little about.

In the year 1997, several things happened. It was the 50th anniversary of Indian Independence, which provoked, in academia and the popular media, renewed interest not only in the freedom struggle and the moment of Independence, but also in Partition. Concurrently, in May 1997, I completed a Masters degree in Anthropology and wanted to pursue research on my own community, the initial spur being a desire to explore why most Sindhis in India do not speak their own language. A few months later, I became part of Dr Ashis Nandys newly started research project at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies and the Committee for Cultural Choices in Delhi.

This project, by the name of Reconstructing Lives, explored memories of mass violence at the time of Partition, its psychological and social consequences as well as the survivors subsequent attempts at coping. This collaborative endeavour, involving researchers in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, was facilitated partly by the Ford Foundation. As part of Ashisdas project, in those early years, I interviewed many elderly Sindhis in Bombay, Ulhasnagar, Gandhidham and Poona who shared with me their memories of Sindh, of Partition, and of the uphill task of resettling in India. This was when I began to discover what the experience of Partition had been for those who had lived through it including my parents.

Over the years, my own research expanded to cover other phases of Sindhi history, both before and after 1947. Ultimately, I started a book on the long-term effects of Partition on Sindhis. When I completed the chapter on the actual experience of Partition, I found that it had become so long and detailed that it had acquired a life of its own. In a sense, my research and writing had come full circle. The result is this volume in your hands.

This is the story of an entire community that was displaced. Since Punjab and Bengal were divided, Punjabi and Bengali refugees in India as well as in Pakistan at least had a region that they could identify with, where their mother tongue was spoken. On the other hand, since Sindh was not divided, Sindhi Hindu and Sikh refugees had no state that they could call their own. They were uprooted from their land and their culture .

Although I have tried to recreate the Sindhi experience of Partition in this book, it is ultimately only an attempt at describing and understanding the reality of those days. The writer Motilal Jotwani says, Can the entire truth about how we lived our lives in the purusharthi camps of Deolali and Kumar Nagar Dhulia be described? His rhetorical question about the ultimate impossibility of capturing in totality the experience of refugee camp life is equally applicable to the entire experience of living as an unpopular minority, of uprooting and exile, and of difficult resettlement.

This book has been a mosaic in the making: I have pieced it together using findings and excerpts from my reading and research, extracts from my interviews, selections from memoirs, biographies and autobiographies, various passages from the press, legends, poetry, as well as silences. While I visited Sindh in 2001 and 2003, the difficulties of obtaining a Pakistani visa in recent years have limited my research there.

One may argue: Why rake up the past, especially a painful past? Is it not time to move on, beyond Partition? I have my reasons for writing this book.

The Punjabi experience of Partition has dominated popular culture in India. We have had books, TV serials and films that depict Partition in the Punjab (although ironically, some of the most popular TV serials, such as Buniyaad and Tamas , have been made by Sindhis). Yet, the terrible carnage that engulfed both halves of the Punjab was absent in Sindh. Many Sindhis may not know that Sindh witnessed much less Partition violence.

Also, in Punjab and Bengal, Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims were more or less equally divided, and so were equally victims and perpetrators of violence. In Sindh, on the other hand, Hindus and Sikhs were a clear minority of less than 30 per cent of the population. Consequently, the Sindhis who suffered from Partition violence were overwhelmingly Hindu and Sikh. It would be very easy to slot the story of the Sindhi Hindu experience of Partition into tidy categories of black and white: Hindus (read Indians) as the victims and Muslims (read Pakistanis) as the villains. However, the reality on the ground was far more complex.