The Hindu Sufis of South Asia

Islamic South Asia Series

Series Editor Ruby Lal, Emory University

Advisory Board

Iftikhar Dadi, Cornell University

Stephen F. Dale, Ohio State University

Rukhsana David, Kinnaird College for Women

Michael Fisher, Oberlin College

Marcus Fraser, Fitzwilliam Museum

Ebba Koch, University of Vienna

David Lewis, London School of Economics

Francis Robinson, Royal Holloway, University of London

Ron Sela, Indiana University Bloomington

Willem van Schendel, University of Amsterdam

Titles

Sexual and Gender Diversity in the Muslim World: History, Law and Vernacular Knowledge , Vanja Hamzic

The Architecture of a Deccan Sultanate: Courtly Practice and Royal Authority in Late Medieval India , Pushkar Sohoni

Sufi Shrines and the Pakistani State: The End of Religious Pluralism , Umber Bin Ibad

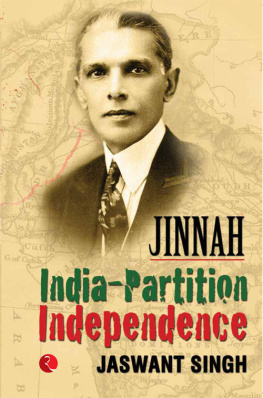

The Hindu Sufis of South Asia: Partition, Shrine Culture and the Sindhis in India, Michel Boivin

The Hindu Sufis of South Asia

Partition, Shrine Culture and the Sindhis in India

Michel Boivin

Contents

Figures

All images belong to the author.

| Three Hindu Sufis with their Muslim murshid s. (a) Qutub Ali Shah, (b) Rochaldas, (c) Rakhiyyal Shah, (d) Mulchand Faqir, (e) Sakhi Qabul Muhammad II and (f) Nimano Faqir. |

| Sufi seats from Sindh in India |

| Hindu Sufi figures and their Sufi connections in Sindh |

| Lal Shahbaz Qalandars alam in Rochaldass darbar |

| External view of two Indian darbar s, Haridwar and Vadodara. (a) The Dada Sain Kuthir, Haridwar, 2012 and (b) The Nimanal Sangam, Vadodara, 2012 |

| Shoba, the gaddi nashin s sister, unveiling Nimanos picture, Mumbai |

| Mulchands tomb in Sehwan Sharif |

| Iconographical agency in the Mulchand and Rochaldass samadhi s. (a) Mulchands altar, Dada Sain Kuthir, Haridwar, 2012 and (b) Rochaldass darbar , Ulhasnagar, 2012 |

| Two mehndi s in Ulhasnagar (India) and Sehwan Sharif (Pakistan). (a) Damodars mehndi procession at Rochaldass darbar , Ulhasnagar, 2012 and (b) Ramchands dastarbandi before the mehndi procession in Sehwan Sharif, 2011. |

| Asan Gul, a Hindu sajjada nashin in Sehwan Sharif |

| Map of the Hindu dargah , Tando Ahmad Khan |

| Pithoro Pirs tomb with the Om. |

Table

| Daily programme of Rochaldass versi in 2012 |

This study is the result of some years being spent here and there in darbar s, talking or observing or translating. Nonetheless, all of the material presented here is not wholly new, meaning unpublished, as various pieces of this study have been presented elsewhere in the time leading up to this publication. Some parts have already been published, in English and in French (see Bibliography), and others presented in conferences or workshops, but these various pieces are now brought together in full, and introduced within this new, and more complete, shape and frame.

I would like to warmly thank all my Sufi dust s for the time and data they have shared with me. As has been the case with much of my other research devoted to Sindh studies, two generations of the Gidwani family from Pune have been keen to share their interests and knowledge of Sufism from Sindh, as well as many other skills regarding the Sindhi language, and different scripts. Also, I must thank Dada Ishwar Balani (19202004), the founder of the Sindhi Community House in London, who pushed me into the world of the Hindu Sufis when he gave me books on Sindhi Sufism in India, back when we met in London in 2002.

I am unable to show how grateful I am to the many Hindu Sufis I have met, and worked with. In Ulhasnagar, Damodar and the late Pritam Das (d. 2015), as well as Daulatram Motwani, Soni Katharia, Jaichand Sharma and Mira Rajani. In Pimpri, my thanks go to Isha Pohani, Gehimal Motwanis daughter. In Mumbai, Dadi Dhan Samtani (d. 2014), Devi Naik, Daulat Kesvani and Dhuru Sipahimalani, with his sister Vina, similarly welcomed my research on the Hindu Sufis, and finally I must here thank Shoba Vaswani. In Vadodara, Murli Kanunga and Suresh Advani, as well as Kamla, whose full name I do not know, and in Delhi and Haridwar, Basant Jethwani and his wife Sonu.

This study was also a golden opportunity for me to observe that the sacro-saint social networks were not always unuseful, since it is thanks to the internet that I was in touch with Manu Bhatia, who made me familiar with Isarlals kalam , which he had published with his cousin Lachhman Bhatia.

Regarding the translations included here in the text, I am most grateful for the help provided by a number of friends, mostly belonging to the Gidwani family from Pune and the Matlani family from Mumbai-Ulhasnagar. Nonetheless, I am the only one responsible for translations when the name of the author is given after a quotation. When it is not the name of an author given, this signifies that I am using another translation, and in this case, this is the name of the translator which is provided. As it will be noted, there is no attempt to provide any academic transliteration.

In 2004, while I was in London for a research programme on Sindhi material, I was told there was a Sindhi Community House in the northern part of the city. Thus, I went to Cricklewood, the area where it was located, and I was welcomed by the shewadaris , the attendants who were in charge of the centre.). This book contained a list of books published by Sindhis, especially Hindu Sindhis, on Sufism. The main part of it had been published in post-partition India in the Sindhi language, and this book offered clear evidence that the Sindhi Sufi tradition was still well alive among the Hindu Sindhis of India, exactly half a century after partition. For me, this find was the equivalent of discovering a new world.

As I had been working on Sindh studies for years, I was well aware that the Sindhi Hindus of Sindh had gone to Sufi shrines, and that they shared their passion for Sufi poetry with Muslim Sindhis and others, especially through Shah Abd al-Latifs Shah jo Risalo . But I had totally ignored the fact that the Sindhi Hindus of India were still linked with Sufi traditions from Sindh. I had totally ignored the fact that the Hindu Sindhis who had fled Pakistan from 1947 onwards had transferred to India not only their Hindu cults but also their Sufi cults. Later on, it took me some years to see how Sufi traditions were still permeating the life of a number of Hindu Sindhis of India. In 2011, I went to Ulhasnagar in Maharashtra for another research project, but I also took this opportunity to pay a visit to some places related to the Sufism of Sindh in India. Gajwani, the author of the small book, was a follower of Sain Rochaldas, whose shrine or darbar was well known in Shantinagar, an area located in Ulhasnagar. In a few months, I went on to become familiar with at least three main Sufi-related paths among the Sindhi Hindus of India, and a number of minor ones.

As an anthropologist, my interest is to understand how, in the early twenty-first century, a number of people in India claiming to be Hindu still maintain a tradition in which the Sufi elements usually associated with Islam are playing a leading part in structuring it, if they are not the core of the tradition itself, and furthermore, I am talking about a tradition with permanent links with Pakistan. In addressing this issue, observation of rituals and interviews with people must obviously be completed and enmeshed in a work on written sources, because, as we shall see, Sufi poetry plays a cardinal role in the setting. The written corpus is mostly made of Sufi poetry in Sindhi, most of it recently published in post-partition India. Another related issue to address is the significance of the Sufi legacy for the Hindu Sindhi community of India. In other words, what did it really mean for them to involve the Sufi legacy in the process of renewing the Hindu Sindhi identity in a brand new environment? And, in more demographic terms, what is the weight and influence of the Sindhi Hindu Sufis in the Indian communities of Sindhi Hindus? As well as in the diaspora?