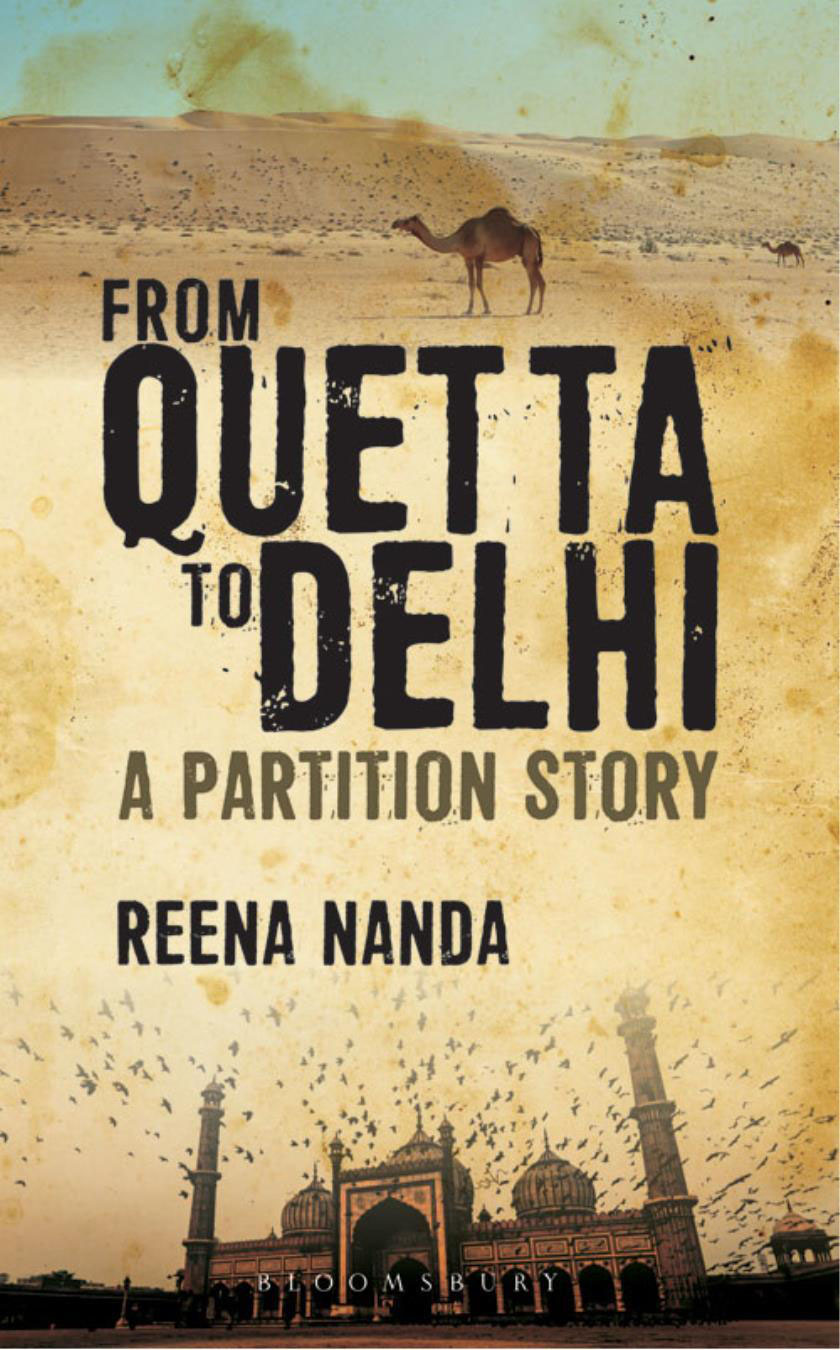

FROM QUETTA TO DELHI

A partition story

FROM

QUETTA

TO DELHI

A PARTITION STORY

By

Reena Nanda

First published in India 2018

2018 by Reena Nanda

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

The content of this book is the sole expression and opinion of its author, and not of the publisher. The publisher in no manner is liable for any opinion or views expressed by the author. While best efforts have been made in preparing this book, the publisher makes no representations or warranties of any kind and assumes no liabilities of any kind with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the content and specifically disclaims any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness of use for a particular purpose.

The publisher believes that the content of this book does not violate any existing copyright/intellectual property of others in any manner whatsoever. However, in case any source has not been duly attributed, the publisher may be notified in writing for necessary action.

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

ISBN 978 93 86 64344 5

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd

Second Floor, LSC Building No.4

DDA Complex, Pocket C 6 & 7, Vasant Kunj

New Delhi 110070

www.bloomsbury.com

Created by Manipal Digital Systems.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com.

Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

Contents

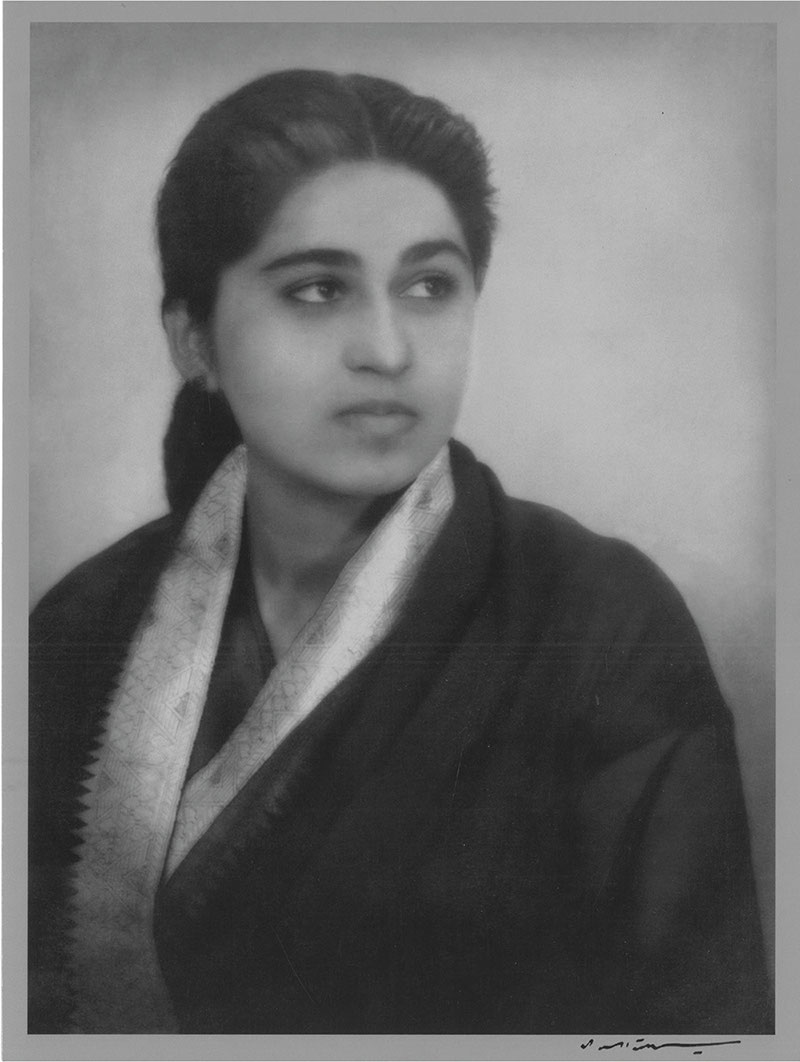

Mrs Shakunt Nanda ne Malik

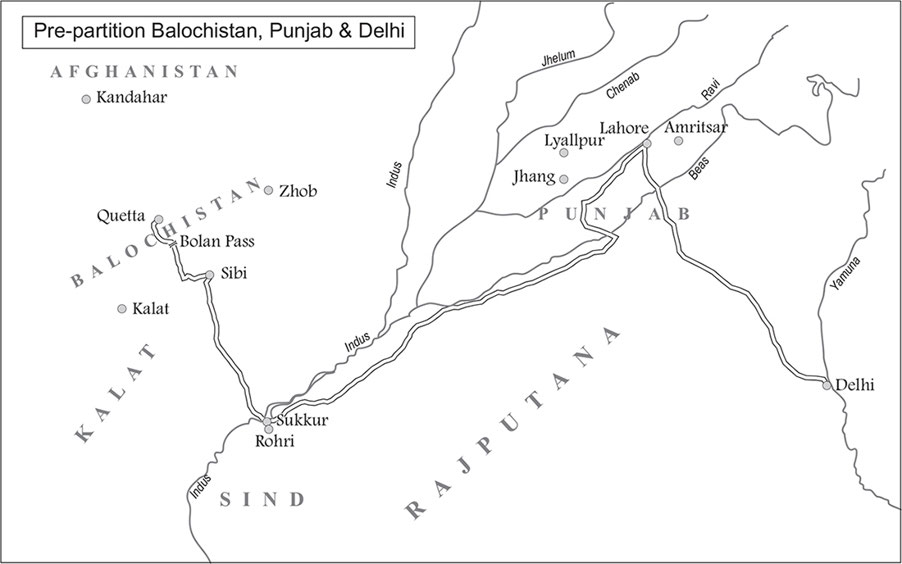

Pre-Partition Balochistan, Punjab & Delhi

Balochistan, a province of Pakistan, is sandwiched between Afghanistan on the north and Iran on the west, and was ruled for centuries by the dynasties of the Persian Empire. The Pre-Harappan archaeological sites of Mehrgarh (7000 B.C.), and Dumb Sadaat, testify to its ancient history. Zoroastrian, Buddhist and Hindu civilisations the Lassi Jats and the Sewa dynasty flourished here before the advent of the Muslim era.

Its rugged, mud-coloured mountains with deep gorges and chasms, enormous boulders and secret passages spell mystery and exciting danger, just like the people inhabiting it. Balochistan is a patchwork quilt of various warring tribes: the Baloch and the Brahui are the dominant colours, though in numbers the Pathans outdo them. The first Muslims to arrive were the Baloch their name means wanderers who left Syria in the 7th century and settled in Iran, from where one branch made their way to Balochistan. When they reached according to one theory they displaced the Brahui and drove them further west and south to Kalat, Sarawaan, and Jhalawar, which still remains Brahui territory. The Brahui language is of Dravidian origin, and the puzzle of how Dravidians came here has not yet been solved. Over the centuries, a great deal of intermarriage has taken place between the Baloch and the Brahui; the latter have become Balochified and are even bilingual, speaking both Balochi and their mother tongue with ease.

The Brahuis and the Baloch are quite similar in appearance: dark-skinned and long-nosed. The men sport thick beards and long, oily ringlets that hang almost to their shoulders. Their turbans are heavy, bulky swathes of white muslin which the Brahuis wind in distinctive coiled rings around the head. The men wear baggy salwars and loose wide-sleeved shirts, while some Brahui clans wear pleated smock-like robes. Some Baloch (who are reputed to have mixed Arab and Indian blood) in particular their Sardars (chieftans) are tall and handsome with a fair complexion. All the tribes Baloch, Brahui and Pathan wear only white garments; the colour is provided by the embroidered waistcoats, the sashes, and the shawls. The Brahui and the Baloch women wear ochre red or blue coloured loose robes or cholas with embroidered yokes and sleeve cuffs.

The Pathans came from Afghanistan and are Muslims like the Baloch and the Brahui people. The Pathans are tall, fair-complexioned, with prominent noses and hawk-like eyes ringed with kohl. They wear white-collared long shirts over baggy salwars. In Quettas Kandhari Bazar, the Pathans would sit at their stalls behind artistically arranged, pyramidal tiers of creamy apricots, crimson plums, golden sardas (conical melons), and blood red Kandhari pomegranates. Green and yellow bunches of seedless Chaman grapes would be heaped in cone-shaped straw baskets the famous kuaras. Some would strum the rabab (a string instrument), while others would drink kahwa, brewed in blue enameled samovars, and watch the Afghan Powindah traders as they would unload their camel caravans that had brought these fruits, carpets, and other goods from Iran, Kabul, and Central Asia. The camels with their headbands and necklaces of brightly coloured, twisted wool, hung with cowrie shells and bells, their colourful woven saddles thrown off would sprawl themselves on the ground to rest. The local cafes would serve kahwa laced with opium that, along with the pulsating rhythms of the music, enticed the men and boys to intoxicating dances. Unlike the Pathans, the Baloch and the Brahui took no part in trade or shopkeeping; they led a nomadic life, being pastoralists and agriculturists. The main occupation of all these tribes in the past had been to war with each other. Over the centuries, however, inter-marriages have increased between the Baloch and the Brahui tribes.

Quetta, the capital city of Balochistan, lay at the crossroads of ancient grazing and trade routes that connected it to Central Asia, Eastern Iran, and Afghanistan. These routes were an offshoot of the old, overland Silk Road through which goods moved back and forth from China. The approach to Afghanistan is through the narrow, torturous Bolan Pass leading to Quetta, which had thus become a strategic location for the British to use in their wars with Afghanistan. In 1876, Robert Sandeman leased Quetta from the Khan of Kalat for Rs 50,000. Eventually, the British forced him to also cede the northern and central parts of the state to them. The British Balochistan Agency was established in these Pushto-speaking Pathan areas whilst the Kalat, Makran, and Las Belas States remained under their rulers. These States were populated by the Brahui and the Baloch tribes.The Khan of Kalat was accepted as the suzerain of Balochistan, to whom the other tribes would pay nominal homage.

When the British declared their intention to grant Independence to India, the Khan filed a case for the return of his sovereignty, since he had been an independent ruler before the British had taken over. He won his appeal, and Kalat became independent in August 1947. However, the British handed over the Balochistan Agency areas administered by them to Pakistan, who requested the British Chief Commissioner to continue in his post. The Khan of Kalat protested against this inclusion in Pakistan, but in April 1948, he was coerced into surrendering, and Balochistan thus became a Province of Pakistan.