John Gillingham - The Angevin Empire

Here you can read online John Gillingham - The Angevin Empire full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Angevin Empire

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Angevin Empire: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Angevin Empire" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Angevin Empire — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Angevin Empire" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Angevin Empire

Second Edition

JOHN GILLINGHAM

Emeritus Professor of History,

London School of Economics and Political Science

First published in Great Britain in 2001 by

Arnold, a member of the Hodder Headline Group,

338 Euston Road, London NW1 3BH

Co-published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press Inc.,

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY10016

2001 John Gillingham

All rights reserved.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 0340 74114 7 (hb)

ISBN 0340 741155 (pb)

Production Editor: James Rabson

Production Controller: Martin Kerans

Cover Design: Terry Griffiths

In memory of Tom Keefe

Contents

List of maps

Royal castles in England, Wales and Ireland

Angevin dominions on the continent, c.1200

Johns itinerary, 11991202

This is a revised and expanded edition of a book first published in 1984 in the Edward Arnold series Foundations of Medieval History (General editor, Michael Clanchy). The purpose of that series was to provide concise and authoritative introductions which would enable students both to master the basic facts about a topic and to form their own point of view. I hope that this second edition, although in all about 25 per cent longer than the first edition, does at least remain concise. In one respect, indeed, it is shorter. The words feudal and vassal appear slightly less often than in the first edition. This new edition is in part a result of the anniversary factor 1999 being the 800th anniversary of the death of Richard I and accession of King John. Three conferences, one on King John at Norwich, two on Richard I at Caen and Thouars, acted as a considerable stimulus to further reflection.

During the intervening years I have owed much to the congenial atmosphere at the meetings of the Battle Conference founded by R. Allen Brown, and to its proceedings, published annually as Anglo-Norman Studies recently described by Frank Barlow as a golden treasury. Battles American equivalent, the Haskins Society, has performed a similarly valuable role; its newsletter, The Anglo-Norman Anonymous, published three times a year, being a useful and often entertaining way of keeping abreast of work in progress.

Since 1984 the study of royal government in England a traditional strength of English historical writing has gone on apace, but it is a particular pleasure here to note how much work is now being done on the French side of Plantagenet history by younger English scholars, several of them thanks to the encouragement and support given by Sir James Holt. I have in mind Judith Everard, Vincent Moss, Daniel Power, Kathleen Thompson and Nicholas Vincent. In this revision I have owed much to their scholarship. I have also had a great deal of help from Jane Martindale, and have benefited from Alban Gautiers kindness in supplying me with a copy of his unpublished mmoire de matrise: Lempire angevin: une invention des historiens ? No doubt about it.

There is a certain nostalgic pleasure in being able to hold Christopher Wheeler, Director of Humanities Publishing at Arnold, responsible for this new edition, since it was he who, nearly twenty years ago now, commissioned its first edition. I am grateful to him for never quite giving up on the attempt to persuade me to produce an expanded version. My thanks also to all those who have helped to see this book through the press: Susan Dunsmore, Emma Heyworth-Dunn and James Rabson.

September 2000

Introduction

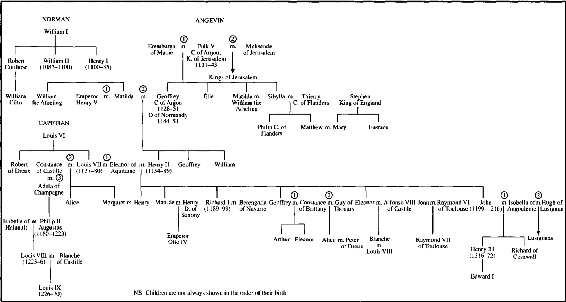

By the Angevin Empire I mean the assemblage of lands held by the family of the counts of Anjou (the Angevins) in the 80 or so years after 1144. In 1144 the count of Anjou, Geoffrey Plantagenet, became duke of Normandy; in 1152 his successor, Henry, acquired Aquitaine (by virtue of his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine); in 1154 Henry also became king of England. He was, in the words of several contemporaries, in extent of his dominions a greater king than any of his predecessors. For the next 50 years, within more or less stable boundaries, this vast accumulation of territories, stretching from the Scottish border to the Pyrenees, was ruled by a series of princes who could claim to be the most powerful rulers in Western Europe: Henry II, Richard I, John. Then in 12024 John lost Anjou, Normandy and much of Poitou (the northern part of the duchy of Aquitaine) to Philip Augustus, the most successful of the Capetian kings of France; in the 1220s the Capetians completed their conquest of Poitou. Thereafter, although the Plantagenets continued to rule both England and Gascony, as well as some other territories Wales, Ireland and the Channel Islands the structure of their lands was very different from what it had been in the second half of the twelfth century. Then the political centre of gravity had been in France; the Angevins were French princes who numbered England amongst their possessions. But from the 1220s onwards the centre of gravity was clearly in England; the Plantagenets had become kings of England who occasionally visited Gascony. The Angevin decades, though they stand squarely within a very much longer period (say, from the eleventh to the fifteenth centuries) during which English and French history were inextricably interwoven, do, none the less, possess a distinct character of their own. The great transformation of the early thirteenth century makes of the Angevin Empire a political entity with a history which is structurally different not only from that of the preceding Norman Empire but different also from subsequent Plantagenet history.

Although for some 50 years (11541204) the Angevin Empire was the dominant polity in Western Europe, there was, so far as we know, no contemporary name for this assemblage of territories. When anyone wanted to refer to them there were only clumsy circumlocutions available for example, the our kingdom and everything subject to our rule wherever it may be used by Henry II, or one of his chancery clerks, in a letter to Frederick Barbarossa in 1157. Nearly 50 years later the continuator of the Annals of St-Aubin (Angers) referred to the lands to which John had succeeded as the whole of the kingdom which had belonged to his father. There was no equivalent to the term regnum Norman-Anglorum devised by the Norman author of the Hyde chronicle to describe Henry Is Anglo-Norman realm. But this chronicler was writing more than 50 years after the Norman Conquest. Fifty years after the Angevin conquest of England, most of the continental lands of the Plantagenets had been lost and, with them, the need to invent a new label had gone.

The term Angevin Empire is a product of the nineteenth century, coined by Kate Norgate in 1887. Her coinage signalled a significant shift away from the assumption that what really counted during the reigns of the kings of England from Henry II to John were purely English matters: the Becket dispute, the making of the Common Law, Magna Carta. This was the assumption that had dominated historical writing since the seventeenth century. For English authors, such as Macaulay, the French possessions were an encumbrance which endangered the sound development of a genuinely English polity.

Had the Plantagenets, as at one time seemed likely, succeeded in uniting all France under their government, it is probable that England would never have had an independent existence. The revenues of her great proprietors would have been spent in festivities and diversions on the banks of the Seine. The noble language of Milton and Burke would have remained a rustic dialect, contemptuously abandoned to the use of boors. England owes her escape from such calamities to an event which her historians have generally represented as disastrous.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Angevin Empire»

Look at similar books to The Angevin Empire. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Angevin Empire and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.