Copyright 2016 Richard Huscroft

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Adobe Caslon Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Gomer Press, Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Huscroft, Richard, author.

Title: Tales from the long twelfth century : the rise and fall of the Angevin Empire / Richard Huscroft.

New Haven : Yale University Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references.

LCCN 2015035080 | ISBN 9780300187250 (alk. paper)

LCSH: Great BritainHistoryAngevin period, 1154-1216. | Anjou, House of. | Great BritainHistory12th century.

Classification: LCC DA205 .H87 2016 | DDC 942.03/1dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015035080

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10987654321

Contents

Illustrations

Plates

Genealogies

Maps

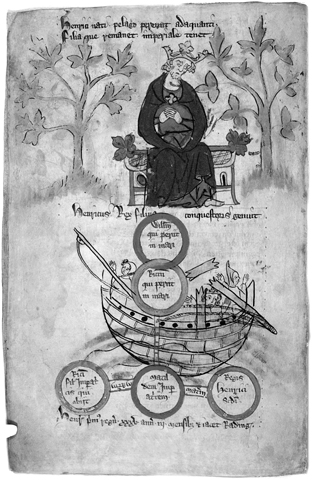

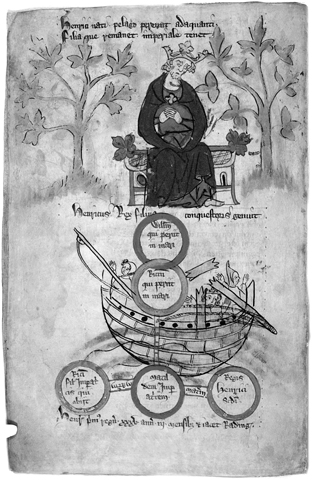

1. In 1120 Henry Is son William Atheling was drowned in the wreck of the White Ship, and civil war followed the resulting succession crisis. In this image from the fourteenth century the king mourns as the ship breaks up and sinks.

2. Framlingham Castle, Hugh Bigods Suffolk powerbase, as it looks today.

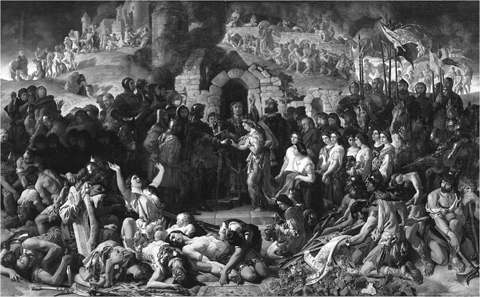

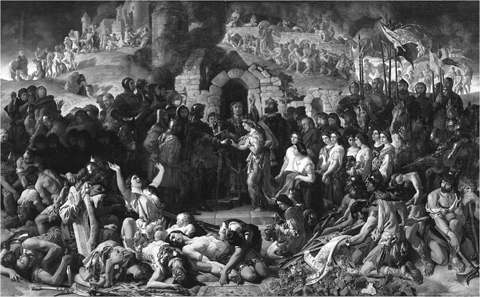

3. In return for agreeing to help Dermot MacMurrough retake his kingdom of Leinster, Strongbow was married to Dermots daughter Aife in 1170. This nineteenth-century interpretation by Daniel Maclise has the wedding taking place against the backdrop of the English siege of Waterford.

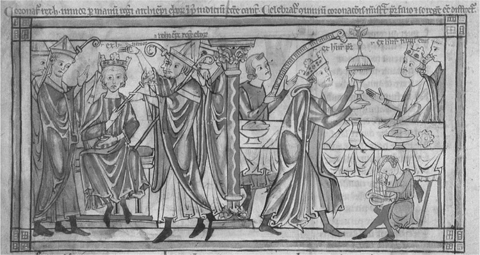

4. This thirteenth-century image shows Roger, archbishop of York crowning Henry the Young King in 1170. At the celebration banquet afterwards, the prince is waited on by his father, King Henry II.

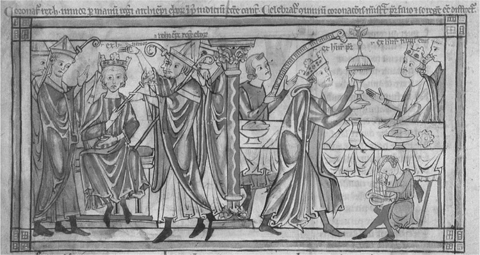

5. King William II of Sicily, Princess Joans first husband, died in 1189. In this late twelfth-century chronicle he is depicted on his death-bed. The crowned figure standing to the right of the dying king is surely Joan looking on.

6. Monreale Cathedral was built by King William II of Sicily between 1174 and 1182. The cathedrals magnificent series of mosaics includes this portrait of Thomas Becket, perhaps the first image of him to be made after his martyrdom in 1170.

7. King Richard I and his sister Joan of Sicily arrived at Acre in the Holy Land in 1191. In this thirteenth-century history of the crusades they are shown meeting King Philip II of France at the gates of the city. Philip was reportedly struck by Joans beauty.

8. Joans silver seal-die (with accompanying impressions in red wax), made in two pieces in the late 1190s. On the left she holds the cross of Toulouse and around the edge she is described as Duchess of Narbonne, Countess of Toulouse and Marchioness of Provence. On the right she holds a sceptre with fleur-de-lis at the end. Around the edge she is described as Queen Joan, daughter of the late king of the English.

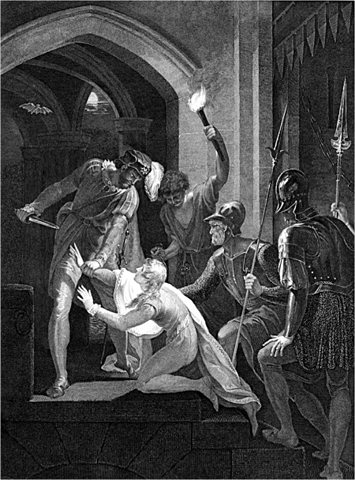

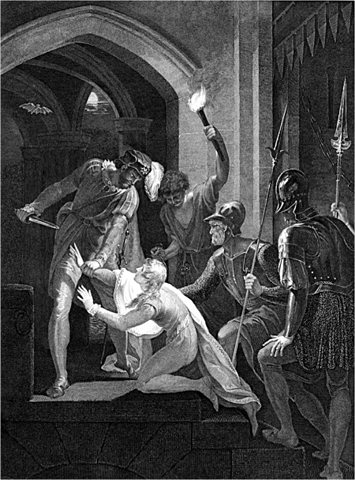

9. Duke Arthur of Brittany disappeared whilst in the custody of his uncle King John in 1203. It is not clear how he died, but this eighteenth-century depiction by William Hamilton of his murder may rightly hold John personally responsible for Arthurs fate.

10. In this engraving by John George Murray, based on the tale told by Roger of Wendover, Archbishop Stephen Langton shows a copy of Henry Is Coronation Charter to a group of barons in the abbey at Bury St Edmunds. Although dressed in medieval clothing, each baron in the engraving was a named nineteenth-century nobleman. They saw themselves as the descendants of the Runnymede barons, responsible for the defence of the principles enshrined in Magna Carta.

11. The seal of Stephen Langton, archbishop of Canterbury. On the reverse is a depiction of the martyrdom of Thomas Becket. By featuring this image on his own seal, Langton emphasised his connection with his murdered predecessor and the suffering they had both experienced at the hands of the Angevin kings.

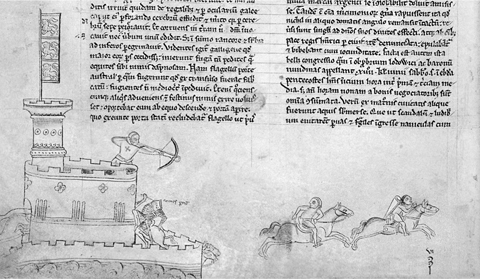

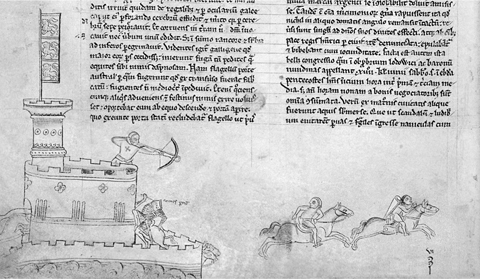

12. In this image drawn in his own chronicle by the thirteenth-century monk Matthew Paris, French troops are seen fleeing from Lincoln after their defeat in battle there in May 1217. Nicola de la Haye had defended Lincoln for King John and his son Henry III, and the royalist victory effectively ended the chances of a French takeover of England.

Acknowledgements

It will be obvious to anyone reading this book how reliant I have been on the work of other historians. Anything remotely novel that I might say here is based in the end on what they have done. Others have helped more directly, of course. Louise Wilkinson read early drafts of two of the chapters, and her comments and encouragement were invaluable at a time when the book was a very long way from completion. The two anonymous readers who more recently pointed up mistakes and misconceptions in my manuscript were also a great help. The staff at Yale have worked tirelessly, too, to make this book better than it would otherwise have been. My editors, Heather McCallum and Candida Brazil, have been patient and tolerant, supportive of the idea behind this book from the start; they have seen it through to publication with great skill and authority. My copy-editor, Richard Mason, has been a model of professionalism; without his meticulous care and his sensitive way with a suggestion, the book would have contained many more errors of detail and infelicities of style. Needless to say, any of these that still remain are exclusively mine. Closer to home, Jo and Tilda have allowed me the time and space to get on with all the work. I could not have written this book without their loving support.

Next page