Sophie McNeill working as a video journalist in Gaza (Sophie McNeill)

As I worked at my desk in Jerusalem, voice messages from Syria would pop up on my phone throughout the day and late into the night.

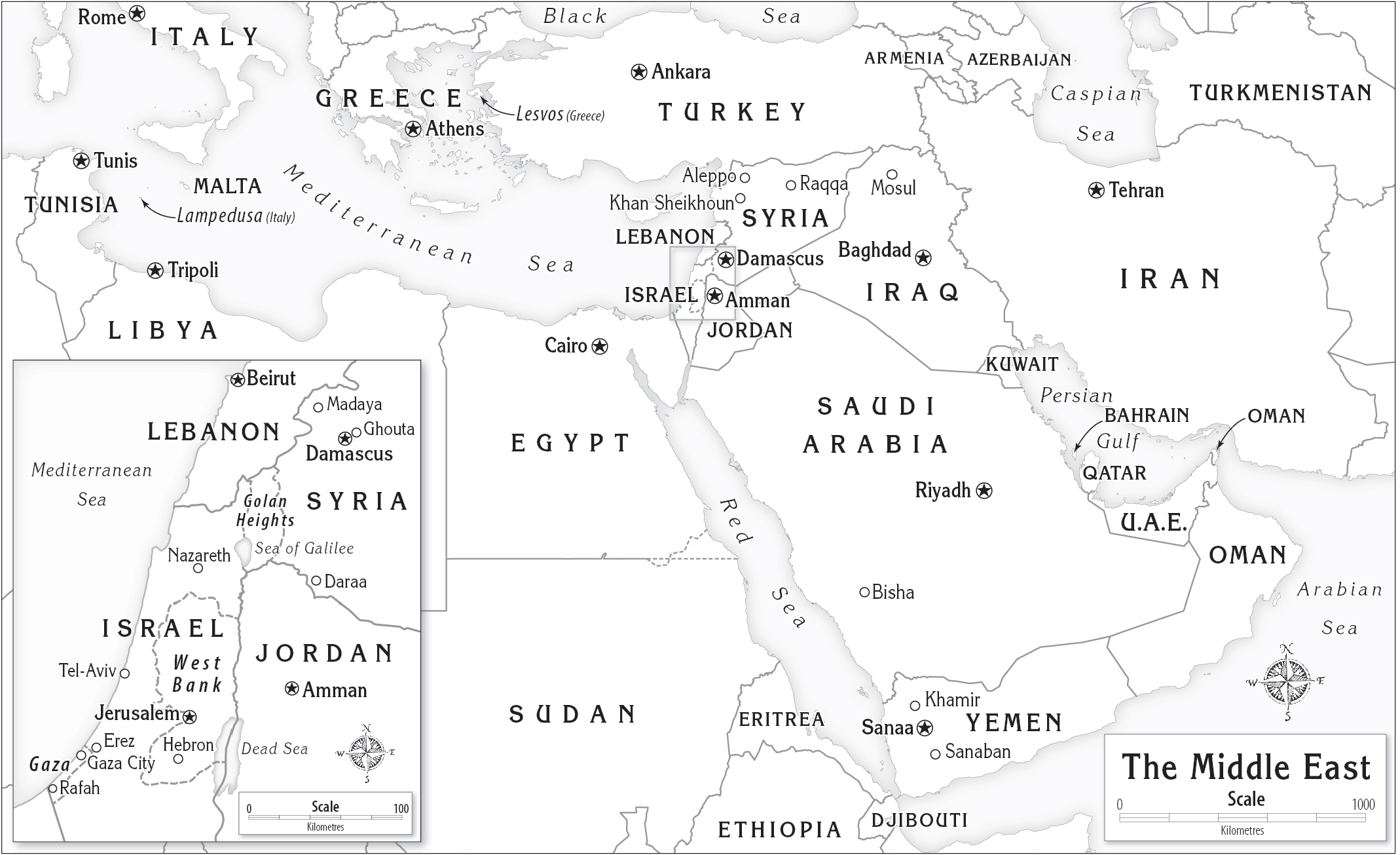

Some were from Dr Khaled Naanaa in his makeshift clinic in the opposition-held town of Madaya, near Damascus. Please, the international community must act fast to save the lives of the people, he begged in one message. Khaled was only about 250 kilometres from where I sat, but his village was besieged, tightly surrounded on all sides by pro-regime forces loyal to Syrias brutal dictator, Bashar Al Assad. For the past five months, no food had been allowed in for Madayas civilians and no one allowed out.

People are starving here, he said. He sent me images of a desperately ill, emaciated baby girl called Amal. Her mother had no milk and she was being fed just water and salt. Two babies in the besieged town had already died from malnutrition. Other small children stared into the doctors camera, their cheeks hollow, their ribs jutting out of their malnourished frames.

I was the first to report the horrific pictures taken in this clinic. And, at first, people sat up and took notice. Children starving to death just 40 kilometres from Damascus? It was a shocking new low, even for Syrias depraved war.

Khaleds photos and videos featured on the front pages of newspapers and news channels around the world. The then US ambassador to the United Nations, Samantha Power, even referred to them at the UN General Assembly.

But nothing changed.

Over the next 15 months, medics documented the deaths of 73 more men, women and children in the besieged town. All had starved to death less than an hours drive from UN warehouses packed full of food in Damascus.

For millions of people across the Middle East like Khaled, international law, the rules of war and the responsibility to protect seem like antiquated theories, discussed in New York at the UN, at legal conferences and in books, but not applicable in real life. On the ground, it feels like the international rule book has not just been thrown out the window but shredded and set on fire. Because when it came to the crunch, most of the well-meaning international principles and systems proved meaningless as millions of the worlds poorest and most oppressed people came under constant bombardment for years on end.

During my three years as the ABCs Middle East correspondent I filmed starving toddlers dying in front of me in Yemen, recorded doctors begging me over the phone for help as their hospitals were bombed in Aleppo, interviewed families who wept on the outskirts of Mosul as they described how ISIS used them as human shields during coalition bombardment, and met distraught children in Gaza whose parents had died after they were prevented from receiving cancer treatment outside the strip, because Israeli authorities wouldnt give them permission to cross the border.

The steady stream of human rights abuses, most perpetrated by state actors upon innocent civilians, was hard to comprehend.

What had our world become?

Ever since I can remember, Id wanted to become a journalist and work overseas. Growing up in Perth, Western Australia, one of the most remote cities on earth, I dreamt of exploring beyond the confines of the small world in which I was raised.

I drew inspiration from reading and watching the works of trailblazing reporters like John Pilger and Max Stahl. When journalists were forbidden from entering East Timor under Indonesian rule, both men had sneaked in as tourists. There they bore witness to the horror of the Indonesian occupation before smuggling out evidence of massacres and torture, and their courageous reporting was critical to East Timors path to independence.

I can still remember the night when I was 14 that I walked out of the Western Australia state library after watching John Pilgers documentary on East Timor, Death of a Nation.

I was in a daze, bowled over by what Id learnt about the horrors of the Indonesian occupation since 1975, the struggle of the people of East Timor for their freedom, and my own countrys complicity in their oppression. I felt strongly that, now I knew what was happening to the people of East Timor, I had to act. I couldnt be aware of what they were enduring and just continue as normal. That felt criminal. I had to do something.

Then and there I signed up to volunteer to work with East Timorese groups, and spent the next few months helping organize rallies and public-awareness events around the upcoming independence referendum in August 1999.

More than 78 per cent of the population voted for East Timors freedom. But we watched the news in horror as Indonesian militia attacked and killed civilians and set about burning East Timor to the ground.

Thanks to reporters like Marie Colvin and John Martinkus, who stayed behind to report what was happening on the ground, there was no denying the unfolding terror. East Timorese were being taken at gunpoint by ship and truck to refugee camps in West Timor, and witnesses reported seeing civilians executed.

Thousands of Australians took action. Building unions laid down their tools, wharf workers refused to unload Indonesian ships, and protestors blockaded the counter of the Indonesian government-owned Garuda airlines at Sydney airport. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of Australians attended snap rallies around the country, demanding the government send Australian troops to intervene and protect East Timors civilians.

In an attempt to appease Jakarta, Canberra had spent months denying the need for an international peacekeeping force in East Timor for the controversial vote. But faced with growing public fury, the Howard government changed their tune, proposing that Australian troops be deployed immediately to lead a multinational peacekeeping force in East Timor.

After intense US and Australian pressure, Indonesia announced that it would accept a UN peacekeeping force. Within days, more than 5500 Australian troops arrived on the ground in Dili to lead the INTERFET peacekeeping force, to restore peace and security, and to facilitate desperately needed humanitarian assistance. A UN political mission, UNTAET, also temporarily governed East Timor and began to rebuild the new country, showing what the international community can do when it takes real action.

Hundreds of East Timorese families who had been sheltering in the UN compound in Dili had been airlifted to safety in Australia. Around 400 of them were staying at the Leeuwin Army Barracks in East Fremantle, just five minutes from my dads house. Every day after school and on weekends Id go there to help teach English to the kids.