Hollywood Sound Design and Moviesound Newsletter

As film students and younger fans experience Big Hollywood Sound in IMAX presentations and digital theaters, many are also discovering action and adventure movies made well before they were born. There is a legacy to be enjoyed in the sound of these films: Blockbuster movies of the 80s and 90s are notable for the extraordinarily dramatic impact of their sound mixing, and the way in which it could immerse audiences in a surrounding space. During this period, a small group of sound professionals in Hollywood wrote and published a critical journal about the craftsmanship, new technology, and changing aesthetics that excited conversation in their community. Their work has been edited and compiled here for the first time.

First published 2017

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

and by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2017 Taylor & Francis

The right of David E. Stone to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record has been requested for this book.

ISBN: 978-1-138-89064-0 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-71014-3 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

Dedicated to Nathaniel Ament-Stone

I recently received from David Stone the following sincere social recommendation when one of his friends relocated to my area: He can drink wine with you and make you laugh. He is toilet-trained and does not bark at passing buses.

I first knew Dave as a fellow teenage filmmaker in suburban Philadelphia in the 1960s, where his particular brand of humor came to life on the set. Our friends were not a unified team of filmmakers but a pair of rival factions, constantly criticizing each others methods. But rather than criticize, Dave would look for a way for his talents to be congruent with it, so that he could make some contribution to anyones project. While doing that, he would look for incongruities that could find expression in jokes, which emerged in a bemused, faux-innocent tone that was laughter-inducing all by itself.

Our adventures in 8mm film production had always seemed to be a kind of microcosm of professional filmmaking: we had our stars, prima donnas, political intrigues, technical crises, wardrobe malfunctions, and our producers who owned the equipment and insisted that everything be done their wayjust as, it turned out, they do in Hollywood.

Another of those talented and creative people was James Morrow, who wrote most of our scripts and is now better known as a novelist. We were really independent filmmakers is his retrospective take on it: If we wanted to make horror films, we made horror films; if we wanted to make slapstick comedies, we made slapstick comedies. None of our parents or teachers or other advisers tried to get us to make one kind of film as opposed to anotherin fact, most of those people would have preferred that wed be doing something else.

Dave came from an artistic family, so thinking and working like an artist seemed to come naturally to him. While the rest of us agonized over our elaborate imitations of Hollywood productions utilizing exotic locations, any props we could find in an attic, and anything else we could beg, borrow, or steal, Dave would simply put some colorful scratches on an expanse of black film leader, accompany it with one of his favorite jazz records, and come up with something worthy of Norman McLaren. This turned out to be our filmmaking apprenticeship, sans mentors of any kindlearning from each other, criticizing each other, being inspired by each other.

After college, we collaborated again on A Political Cartoon (1974), a short film shot in 16mm, which I co-directed with Jim Morrow. Dave and I were in the editing room when the time came to cut the sound effects track for a crucial scene: An animated cartoon character had been deprived of his vital India Ink. He was catatonic, and as close to death as a cartoon character could be, so his desperate creators had to improvise an ink transfusion . It was Daves idea to begin the process simply, by dropping in existing sound from outtakes, adding that to the sync production sound, which never would have occurred to me. While working as an inbetweener at a Hollywood animation studio, Dave got involved professionally with sound editing and became a different kind of artist, creating funny combinations of sounds.

More sophisticated sound editing work eventually followed on some of the biggest live-action features of the 1980s and 1990s, and he brought the same artistic sensibility to them. This career climaxed with an Oscar for his work on Bram Stokers Dracula (1992), where his sound effects for Jonathan Harkers first appearance at Count Draculas castle suggested that all the winds of Hell had been let loose in Transylvania. In a later discussion of the film, a coworker commented on the helpful way the entire post-production crew stepped up to the plate to provide walla for the insane asylum scenes, when additional vocal background was needed. Daves humble reply to this kudo was that, after a steady diet of 16-hour workdays, making insane asylum-type noises was really no great stretch.

Daves insistence that a good editor is most accurately seen as an artist, rather than a technician, squares with what I observed on professional sets: every crew is loaded with artists, whether they light the set or populate the backgroundcostume designers, art directors, makeup artists, cinematographers, set dressers, actors, and editors. A technological art form calls into being a technological artist.

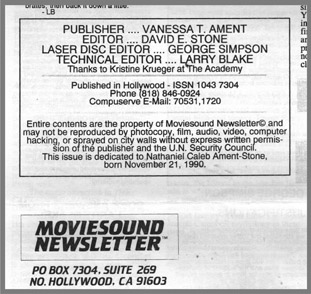

Thats how a cultural artifact like Moviesound Newsletter is critical: Publisher Vanessa Ament, Dave, and their peers lived through a revolution in the expansion and evolution of skills in their field. Dave and Vanessa had not only the writing and editing skills necessary to get this little newsletter out on a regular basis, but they had the contacts, the vocabulary, and (most of all) the perception and fascination with their fellow artists ways of working to document this revolution as it was occurringmaking this compilation a technical and historical landmark.

I remember a meal with several film colleagues where Dave combined words and physical objects to create a matchless description of the way the experience of filmmaking fails to be any kind of predictor of the quality of the eventual film being made: Picking up three unrelated dinner table props (I believe it was a fork, a napkin, and a salt shaker), he gave each one a metaphoric identity, saying, Good Work ExperienceGood Sound JobGood Film. Then he threw up his hands and exclaimed, They have nothing to do with each other! He made his point and, once again, got his laugh. But Dave could always make the worst film into a good experience.