In 1902, The Singleton Argus ran the obituary of local man Phillip Kelly, who had died aged 85. Kelly, originally a native of London, had been a resident of the Singleton area for 60 years and had left a wife, seven sons and two daughters, including my grandmother, Sarah. Kelly was respected by all who knew him and was an unofficial local historian, known for his many anecdotes and interesting reminiscences of the history of the town. The obituary did not mention that Phillip Kelly had been a convict, assigned to Robert Scott at Glendon, nor that his 60 years in the district referred to the time after his sentence of seven years had expired, rather than after he had actually arrived as a fifteen-year-old in 1834.

It is hardly surprising that Kellys obituary did not mention his convict past. A previous conviction was not deemed something worth reminding people of, be it as a colonial convict or a later prisoner, and Kelly had worked hard to establish himself in the community. He died at a time when convicts were being excised from the written histories of the Australian colonial past, despite their experience still being very much in living memory. It is likely that, as Kelly was a long-term resident of a small country town, many of Singletons residents, particularly the older townsfolk, knew that he had been transported, as was the case for many of the families in Singleton and across the other towns in the valley. It was no secret in our family; my grandmother could remember the scars on her fathers back from the floggings he received as a convict.

Kelly and his convict colleagues were part of what historian Tom Griffiths has called the suggestive silences of Australian history, where convict and Aboriginal histories, especially concerning cruelty or violence, were left out or glossed over as a footnote in the history of progress and development. This was as much the case in the Hunter Valley as anywhere else. This dissolution of the convict memory obscured the true importance of their contribution to the character and development of the Hunter Valley and to its later success as an agricultural and industrial region.

As we have seen, those convict men and women lived on; many had families and moved into the fledgling towns and villages to take up a trade, open a hotel or start a business. Around half of those male convicts who remained in the area married, many to convict women or to women in the next generation of arrivals. Phillip Kelly, for example, married Bridget McGarry, a refugee from Irelands famine, in September 1850. After Bridget died in the late 1850s, he remarried in 1861 to another recent arrival, Cecilia Sweeney, nineteen years his junior. Both lived on in Singleton into the first years of the twentieth century.

Thomas Dunn, the constable ambushed at Fal Brook in 1835, arrived with a life sentence in 1822. He was in the very first wave of convict workers into the Hunter after the closure of the penal station. Like Kelly, he also married and settled in the district, taking fellow convict Rose McGarry (no relation to Bridget McGarry) as his wife in April 1832. Thomas and Rose represent the other line of my family tree. Rose had arrived on the Edward in 1829, sentenced to seven years. Sent first to the Parramatta Female Factory, her involvement in a riot there saw her among the first women sent to the Newcastle Female Factory in 1831. Married the following year to Dunn, as the wife of a convict constable she saw the potential for violence on the frontier firsthand. She probably nursed Dunn after the savage beating, tending his cuts and bruises. But they too survived, moving about the valley until they settled close to Singleton, where they stayed.

These two families were like hundreds of others around them, trying to build lives and set down roots. Their success built families who stayed in the Hunter, setting the foundations for the valley as we know it today.

The Brokenback Ranges that flank the southern edge of the Hunter Valley. Aboriginal pathways criss-crossed these mountains for millennia. The British found their way through in 18191820. (Authors collection)

One of the most significant rock art sites in the Hunter Valley, Baiame Cave in Milbrodale is a powerful representation of the deep Aboriginal spirituality and connection to Country in the region. (Authors collection)

The Lady Nelson, in which Lieutenant James Grant undertook the first official survey of the Hunter River in June 1801. (State Library of New South Wales [SLNSW] ML 590)

Ferdinand Bauers view across the settlement at Newcastle, 1804. This is the first view of the penal station and shows the rudimentary beginnings of the town. The house of the commandant Charles Menzies and the flagstaff are on the hill to the right. (SLNSW, SV1B/Newc/1800-1809/1)

Joseph Lycetts painting of Newcastle looking towards Prospect Hill, c. 1818. Comparison to Bauers work from fourteen years earlier illustrates the spread of the penal station across the core of modern-day Newcastle. (Newcastle Art Gallery collection, Gift of Port Waratah Coal Services in 1991, NRAG Foundation)

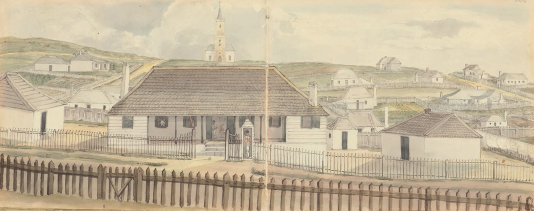

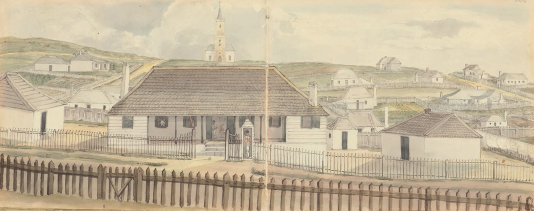

The soldiers barracks with Christ Church visible on the hill in the distance, c. 1820. This is one of a series of watercolour studies done by Edward Close during his time as Engineer and Inspector of Public Works at Newcastle. (National Library of Australia [NLA] PIC Draw 8631#R7273)

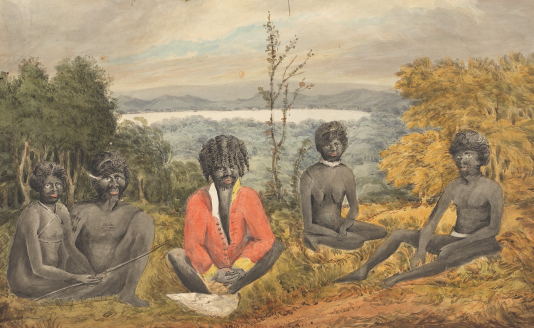

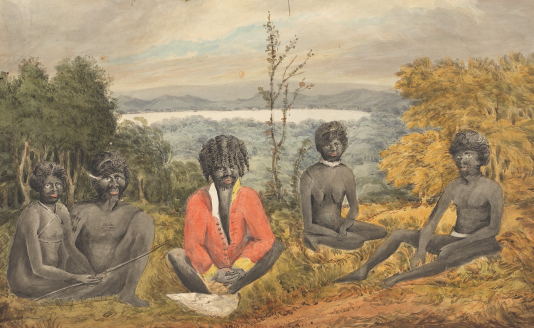

Portrait by Captain James Wallis of five unnamed Newcastle Aboriginal men and women, including one in a soldiers red coat, c. 1818. (SLNSW, SAFE/PXE 1072)

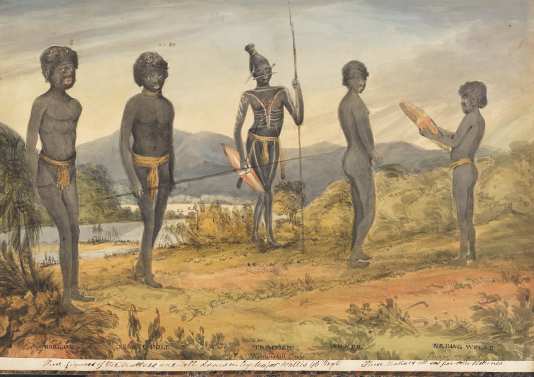

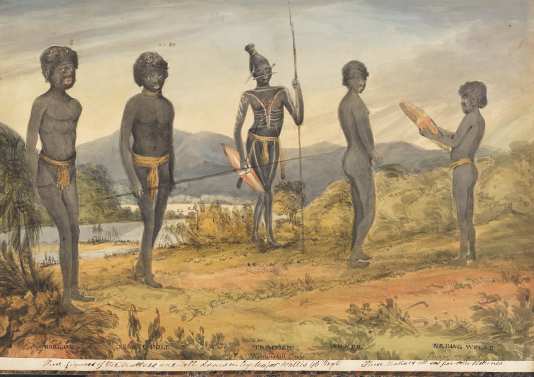

Portrait by James Wallis of five identified Newcastle Aboriginal men, including Burigon on the far left, Nerang Doll, Trimmer in full warrior dress, Walker and Nerang Wogee with the shield, c. 1818. (SLNSW, SAFE/PXE 1072)

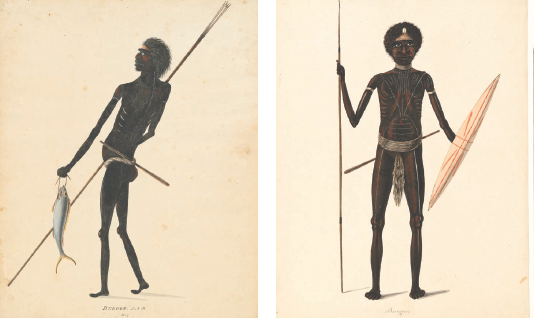

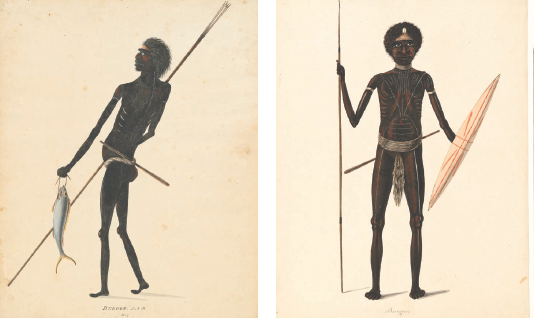

Two views of Burigon/Burgun by convict artist Richard Browne, c. 1819. Although rudely executed, Burigon is portrayed with the accoutrements of everyday life. In one he is shown with a four-pronged fishing spear or mooting; in the second he holds a single prong camoy, his body painted in red ochre. A waddy is stuck through his belt in both portraits. (NLA PIC Solander Box A64 #T2791 NK149/D [Left]; PIC R8947 LOC Box A65 [Right])

Next page