1,000

books

to rEAD

BEFORE

you diE

A Life-changing list

james mustich

with Margot Greenbaum Mustich, Thomas Meagher, and Karen Templer

workman publishing new york

The only advice, indeed, that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions. If this is agreed between us, then I feel at liberty to put forward a few ideas and suggestions because you will not allow them to fetter that independence which is the most important quality that a reader can possess.

Virginia Woolf, How Should One Read a Book?

To my parents, Annette and Jim Mustich, for a thousand and one books and the home that held them.

To Emma and Iris, so they might explore the landscape in which their father found his way.

To Margot Greenbaum Mustich, whose intellect and diligence have ensured this book a life, and whose love has enriched mine.

And to the memory of Peter Workman, whose inspiration engendered this volume and countless others.

Contents

Edward Abbey to Jane Austen

Natalie Babbitt to A. S. Byatt

Roberto Calasso to Will Cuppy

Lorenzo Da Ponte to George Dyson

Umberto Eco to Frederick Exley

Anne Fadiman to R. Buckminster Fuller

William Gaddis to Giovanni Guareschi

Michihiko Hachiya to Kazuo Ishiguro

Shirley Jackson to Norton Juster

Franz Kafka to Tony Kushner

Pierre Choderlos de Laclos to George Lyttelton

Amin Maalouf to Robert Musil

Vladimir Nabokov to Kathleen Norris

Barack Obama to Ovid

George Packer to the Quran

Jonathan Raban to Witold Rybczynski

Rafael Sabatini to Wislawa Szymborska

Tacitus to Anne Tyler

Ellen Ullman to Susan Vreeland

D. J. Waldie to Tim Wynne-Jones

Malcolm X to Carl Zuckmayer

Introduction

In the Company of Books

I caught the reading bug as a child from my mother, who is still, at eighty-nine, the most constant reader I know. As library hound, student, English major, aspiring writer, and then, and enduringly, bookseller, I surrounded myself with books, which spontaneously sprouted and grew into piles in whatever room I inhabited. Parenthood only compounded the circumstance, and the house I share with my wife, Margot, remains filled with the picture books, chapter books, and YA novels that accompanied our two daughters on their journey to adulthood. Books are everywhere I look, and I like it that way; I suspect you share something of the feeling, or you wouldnt have picked up this one.

Naturally enough, one of my first jobs was working at the local bookstore in Briarcliff Manor, New York, that had fed so many of my fledgling literary enthusiasms. There I unpacked shipments from publishers, stocked front-of-store displays with new releases, and found room for backlist titles on the always crammed shelves. I learned to listen to customers and, eventually, to make useful, interesting, and potentially life-changing recommendations. That last hyphenated adjective may sound grandiose, but as Roger Mifflin, the protagonist of Christopher Morleys The Haunted Bookshop, puts it, steadfast booksellers are missionaries who seek to spread good books about, to sow them on fertile minds, to propagate understanding and a carefulness of life and beauty.

With that mission in mind, in 1986 I cofounded a mail-order catalog called A Common Reader, and spent the next two decades running that venture, which, luckily for me, consisted of writing about books old and new, of every subject and style. Supported by a small band of colleagues, I managed to grow the enterprise until we were mailing rich commentary on scores of titles every three weeks to hundreds of thousands of readers across the United States.

In the early 2000s, Peter Workmanfounder of Workman Publishing and to me both mentor and friendand I began talking about the book you are now reading. Over the course of many book-soaked conversations, the idea of 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die took shape. Again fate had pointed my simple desire to be immersed in written words toward a new destination. It turned out to be farther away than either of us thoughtthe book has been fourteen years in the making, and I regret that Peter is not alive to see it published.

Any exercise in curation provokes questions of discernment, epistemology, and even philosophy that can easily lead to befuddlement, and in the case of books, since they are carriers of such varied knowledge in themselves, it can be paralyzing. A book about 1,000 books could take so many different shapes. It could be a canon of classics; it could be a history of human thought and a tour of its significant disciplines; it might be a record of popular delights (or even delusions). But the crux of the difficulty was a less complicated truth: Readers read in so many different ways, any one standard of measure is inadequate. No matter their pedigree, inveterate readers read the way they eatfor pleasure as well as nourishment, indulgence as much as education, and sometimes for transcendence, too. Hot dogs one day, haute cuisine the next.

Keeping such diversity of appetite in mind, and hoping to have something to satisfy every kind of reading yen, I wanted to make 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die expansive in its tastes, encompassing revered classics and commercial favorites, flights of escapist entertainment and enlightening works of erudition. There had to be room for novels of imaginative reach and histories with intellectual grasp. And since the project in its title invoked a lifetime, there had to be room for books for children and adolescents. What criteria could I apply to accommodate such a menagerie, to give plausibility to the idea that Where the Wild Things Are belongs in the same collection as In Search of Lost Time, that Aeneas and Sherlock Holmes could be companions, that a persuasive collection could begin, in chronological terms, with The Epic of Gilgamesh, inscribed on Babylonian tablets more than four thousand years ago, and end with Ellen Ullmans personal history of technology, Life in Code, published in 2017?

I came upon the clue I needed in a passage written by the critic Edmund Wilson, describing the miscellaneous learning of the bookstore, unorganized by any larger purpose, the undisciplined undirected curiosity of the indolent lover of reading. There, I knew instinctively, was a workable conceit: What if I had a bookstore that could hold only 1,000 volumes, and I wanted to ensure it held not only books for all time but also books for the moment, books to be savored or devoured in a night? A shop where any reading inclinationbe it for thrillers or theology, or theological thrillersmight find reward. In the end, I was back in my favorite haunt, a browsers version of paradise.

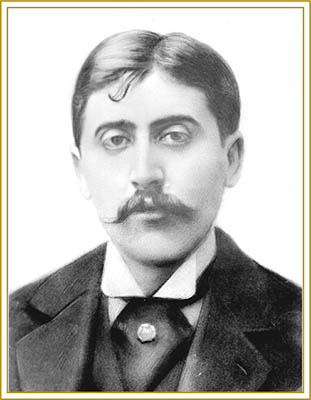

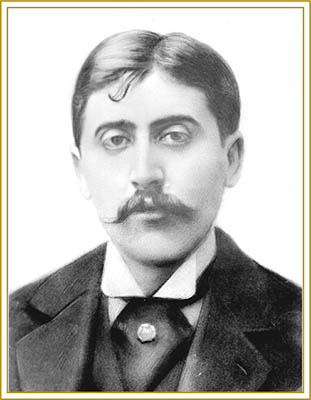

Marcel Proust

That end, of course, was only the beginning. I still had to wrangle with myriad knotty concerns. I spent monthswas it years?arranging and rearranging lists of several thousand titles. What classics were compelling enough to earn a spot? Which kids books so timeless they made the grade? What currents of thought retained their currency? Which life stories were larger than their protagonists life span? Not least, what authors did I love so much that they might be ushered in without their credentials being subject to too much scrutiny?

Next page