THE ART OF

LOOKING UP

CATHERINE MCCORMACK

Introduction

Why do we look up? In childhood we look up for reassurance, guidance and a model of the future that awaits us. As humans we are hierarchical and believe that the higher up something is, the greater its importance, and we consequently tend to desire things that are tantalizingly out of reach. As humanity we have looked up at the sky above us to understand our place in the universe, using the constellations of the stars to chart our voyages. In looking up we reflect on our gods and construct the stories of our creation. In looking up we encounter the frontiers of our knowledge in the firmament of sky and stars that we have tried so hard to conquer and inhabit, first with air travel, then through space. For the sky binds us to our planet but also presents a boundary that we long to break through. Looking up was led by a desire for transcendence beyond ourselves and this is, perhaps, why it is here that we have long projected our religious, cultural and social beliefs and philosophies.

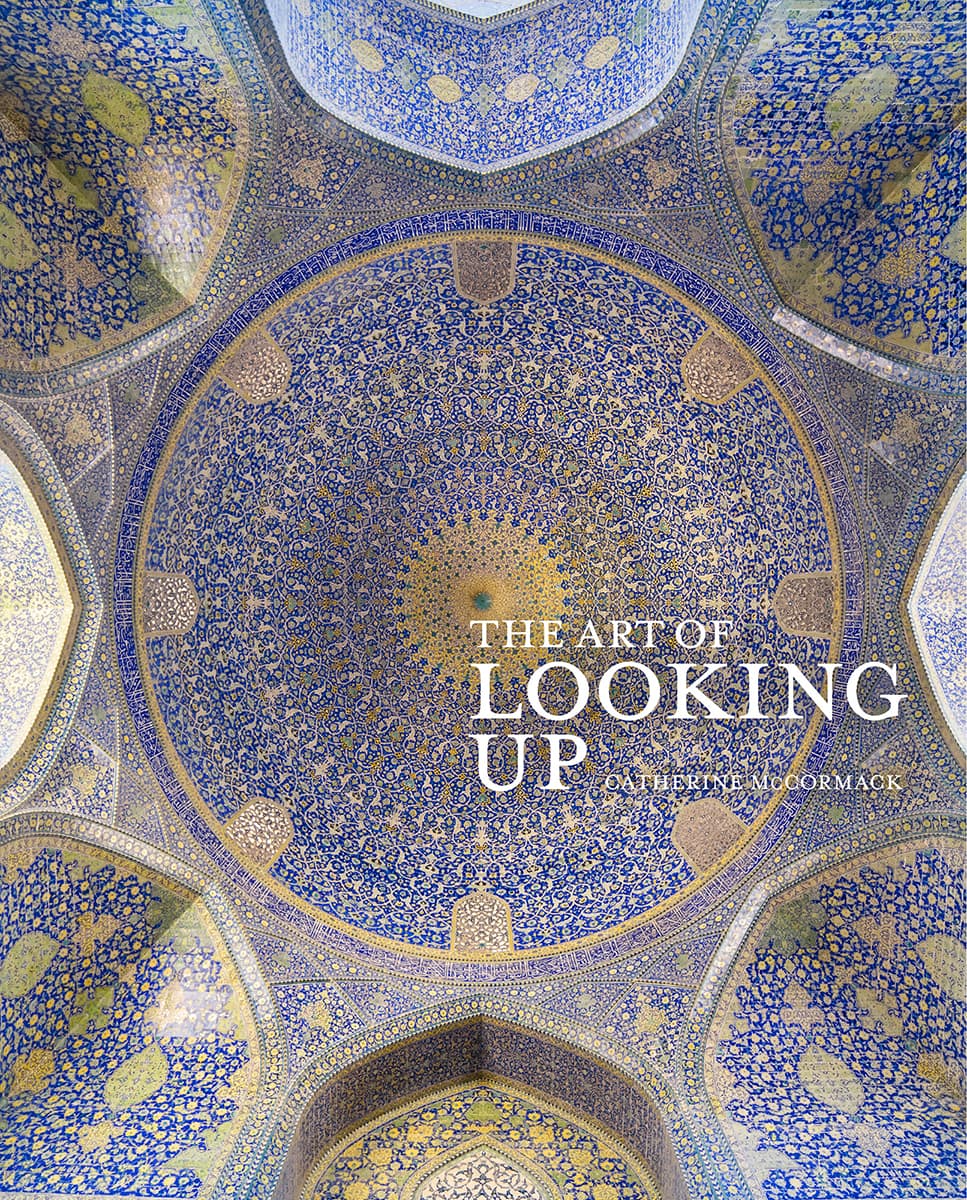

This might also explain why the blank spaces of our buildings the domes, the vaults, the ceilings have proved irresistible to emblazon and decorate; they act as a version of the sky that we can control and occupy to our own design. The words are linked linguistically, after all. The English word ceiling is influenced by the Latin term caelum meaning sky or heaven.

This must be why we have designated the sky as the source of all that we revere, to the abandonment of the ground beneath us. In the early 1500s, Leonardo da Vinci said that we knew more about the movement of the celestial bodies above than we do about the soil underfoot. But it has not always been so. Before the end of the Neolithic period (c. 3000 BCE), we looked into the earth for our spirits and gods. The great sky-god cults emerged at the beginning of the Indo-European age and their dominance has not waned. They are all present in the works selected for this book from Jupiter, the king of the pagan gods hurling his thunderbolts, Hindus Krishna, Shiva and Vishnu and the spiritual deities of Buddhism, to the Christian god of judgment and creation and the divinity of Islam, conveyed not in pictorial form, but sublimated into pattern, colour and light.

The architecture of our religious buildings leads our gaze upwards, both in the soaring vaults of early medieval European cathedrals, and the dome, its circular shape a symbol of heaven and a metaphor for eternity from Islam to Christianity. And because we have placed our gods in the sky, looking up fosters aspirations of immortality. The ceiling is an aggrandizing space for those who have the means to occupy it in visual form, whether in the story of Christian saints or the apotheosis of popes and prince-bishops, or even artists, as in the case of Salvador Dals Palace of the Wind ceiling, which depicts his apotheosis into the subconscious mind.

The starry vault of Sainte-Chapelle, the royal chapel within the Palais de la Cit, consecrated in 1248. Soaring Gothic architecture draws the gaze and mind upwards to an imagined divine firmament, while light filters through the radiant polychromatic stained glass to create an experience of heaven on earth.

This relationship with the sky leads to the prevalence of the colour blue in many examples of ceiling art, from the mosaics of Ravenna to Cy Twomblys ocean of azure in the Louvre Museum, known only as The Ceiling, or the inimitable blue of Gladys Deacons eyes as they glare down imposingly from the North Portico of Blenheim Palace with an otherworldliness that is firmly secular. It is worth remembering that, in painting the blue of the sky, we have had to mine the ground for the precious lapis lazuli pigment that in fifteenth-century Florence produced the colour considered to be the most perfect, illustrious and beautiful (according to Italian artist Cennino Cennini). Although the story of painting the sky is a story of blue, this is not the only colour to be found here, rendered in materials that range from glass to mosaic and stone and even the wing cases of scarab beetles. Lets not forget that, while we are looking up, figures in the images above are looking down on us. The techniques of sotto in su (from below to above) and trompe loeil (trick of the eye) are intended to terrify, inspire and entertain, making spectators flinch as they anticipate the overspill of the illusory world of the painting into their own space. This relationship between looking up and what is below plays out in Giulio Romanos Sala dei Giganti in Palazzo del Te, Mantua, in which the sky gods of Mount Olympus battle with the mysterious forces of the primordial earth in the form of the giants.

There is a conspicuous absence of women artists in the book. This does not reflect a lack of capability among women, but rather a dearth of opportunity throughout the history of art. For women across all continents and cultures were prohibited from the art-academy training that typically led to commissions in the public and private spaces that feature in this book from the grand contracts to embellish the palaces of the wealthy and powerful to the religious buildings that defined the state, or the political halls of the establishment order. And there is no way of knowing the gender of the anonymous artisans of mosaic and stonework whose work is their silent testimony in places such as the Neonian Baptistery or at the Alhambra and Topkap palaces.

Painting as an art in itself, and also one that combined poetry and intellect, was considered a male profession. Indeed, there was even a taxonomy of masculinity within painting in Italian art theory of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries one in which fresco was considered the most virile painting technique, reserved for such spaces as the vaulted ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, or the smaller vault of the Palazzo Farnese in the same city, or the triumphalist all-encompassing world view of Tiepolos staircase in the Wrzburg Residence.

There are a few exceptions to this gendered rule, examples that fell through the gaps, but that history has not devoted enough attention to until recently. For example, Artemisia Gentileschi (15931653) was born into a family of male painters and learnt her profession with her brothers in her fathers studio. A successful artist in her own right, she joined her father in London to paint the nine canvases of the Allegory of Peace for the ceiling of the Queens House in Greenwich, a work that is now installed in Marlborough House, London. But her contribution has been squabbled over in the scholarly archive, with the voices that dispute her hand as vocal as those who attest her presence. Founding member of the Royal Academy in Britain, in 1768, Angelica Kauffman (17411807) was a self-professed history painter. The most illustrious category an artist could identify as, this was almost exclusively reserved for male painters by virtue of the fact that women were prohibited from studying nude models fundamental to painting in the academic style. Kauffman painted four images known as the