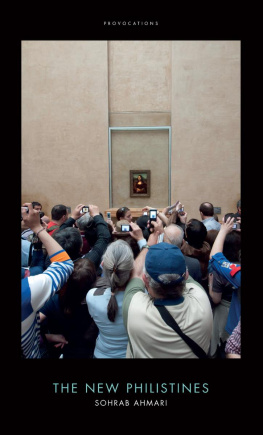

Ahmari - The New Philistines:

Here you can read online Ahmari - The New Philistines: full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 2016, publisher: Biteback Publishing, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The New Philistines:: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The New Philistines:" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ahmari: author's other books

Who wrote The New Philistines:? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The New Philistines: — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The New Philistines:" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

I dedicate this book to my maternal grandparents,

Seyyed Mehdi Ziae and Farah Bovani. And to

Ting Li Ahmari, my wife, best friend and chief critic

(PROVERBS 5:18).

T HIS IS A book about a crisis in the art world.

Which means that it covers well-trodden ground. In 1897, for example, Leo Tolstoy railed against the perversion of art in his day. Bad art had come to be considered good, the Russian novelist fretted, and even the very perception of what art really is had been lost. You can find equally stiff denunciations of alleged artistic perversion going back centuries, all the way to Aristotle.

So why write, or read, another polemic about culture and todays art world? Because the things that are going wrong with art now are qualitatively worse than all that came before.

Tolstoys gripes notwithstanding, art in the late nineteenth century still sought after beauty and truth. And this remained the case for much of the twentieth century, when modernism took the world by storm. Modernist art promoted radical ideas about what counts as beautiful and about how to convey truth, and it rebelled violently against old aesthetic and moral standards. But the modernists felt acutely the weight of those standards. Overturning any old order, after all, implies a measure of respect for its authority. Otherwise the revolution would come too easily, and the revolutionaries would draw no satisfaction from victory.

By contrast, todays art world isnt even contemptuous of old standards it is wholly indifferent to them. The word beauty isnt part of its lexicon. Sincerity, formal rigour and cohesion, the quest for truth, the sacred and the transcendent none of these concerns, once thought timeless, is on the radar among the artists and critics who rule the contemporary art scene. These ideals have all been thrust aside to make room for the art worlds one totem, its alpha and omega: identity politics.

Now, identity has always been at the heart of culture. Who are we? What is our nature? How are we as individuals and as groups distinct from each other, from the animals, from the gods or God? But identity politics cares little for such open-ended questions. Its adherents, the identitarians, think they already have the answers: a set of all-purpose formulas about race, gender, class and sexuality, on one hand, and power and privilege, on the other.

Contemporary art is obsessed with articulating those formulas in novel ways. If you find yourself wondering why nothing stirs inside you when you visit that latest exhibit in SoHo, or watch that strange new piece of performance art in Los Angeles, or take in that random collection of ugly objects that passes for an installation at the Tate Modern, you arent alone. Chances are, you are suffering the effects of the relentless identity-politicisation of the arts.

This degree of politicisation means that Western art no longer fulfils its central role, to serve as a mirror and repository of the human spirit. The state of affairs should worry not just artists and art lovers, but anyone who cares about the future of Western civilisation. How we got to this point how identity politics came to disfigure our culture is the main subject of this polemic.

The book ranges freely over the visual, performing and literary arts, drawing examples from dance, film, painting, theatre and the novel, as well as newer forms such as installation, performance art and video. The emphasis is on high art, the kind on display at museums, art institutes and serious galleries. But I also touch on how identity politics shapes popular culture, and how compliance with its edicts is increasingly the measure by which we judge movies and TV.

A few caveats. First, a book of this length cant be systematic or comprehensive, nor does it claim to be. I readily concede, for example, that identity politics isnt alone to blame for an art world that inspires little more than bemused ennui in the millions who still turn to it, in vain, for beauty and truth. The wider collapse of critical standards, the role of big money in the art world, the deleterious effects of social media on our attention spans, the sense that art has no new frontiers left to cross these questions are for the most part beyond the scope of this book, which focuses on one calamity among many.

Nor is this book written with an expert or academic readership in mind. It is addressed to all who dutifully attend the important gallery openings, theatre productions and museum retrospectives but find nothing that moves them. Im one such malcontent.

I was born and raised in Iran, one of the worlds least-free societies, before immigrating to the West as a teenager. In the Islamic Republic, culture was (and is) a deadly serious business. Create the wrong kind of art, or hold the wrong opinion about art, and it could mean your liberty or even your life. Soon after seizing power in 1979, Irans ruling Islamists staged a cultural revolution in which thousands of ideologically unfit faculty members and students were purged from the universities. The revolutionaries also raided the countrys great libraries, using black markers to methodically cross out nude pictures in the art books.

That a theocratic police state could be this afraid of Renaissance nudes in books taught me early on about the power of great art and its connection with human freedom. And it makes me wonder: what does it say about the Free World today, that much of our art is so doctrinaire, so incapable of conveying any meaning other than the imperatives of identity politics?

The answer to that question has implications that go far beyond the art world itself. Yet as the American critic Camille Paglia has written, artists today are too often addressing other artists and the in-group of hip cognoscenti. The cognoscenti put a high premium on obscurantism in the way they write and speak, and in the works they create. The intimidating jargon and layers of self- and meta-reference combine to seal off the art world, discouraging outsiders from daring to criticise. If it takes a political journalist and the methods of political journalism to expose these discussions to a wider public, so be it.

Throughout the book, I write of beauty and truth as values to which all art should aspire. Rest assured, students of aesthetics, I know that neither concept is easy or straightforward. I also recognise that beauty and truth are far from synonymous in art. Very often in the history of Western art, the two have been held in opposition to each other.

To grossly oversimplify things, beauty can be a sign or reflection of truth, but it can also seduce us away from truth. This age-old debate neednt detain us, however, simply because contemporary identitarian art rejects the very possibility of objective, universally accessible beauty and truth. For our purposes, you are welcome to define beauty and truth as broadly or narrowly as you wish, and you can see the two ideals complementing or contradicting each other. So long as you reject the rejection of universal truth and objective beauty, you are in my camp. If you agree that, say, Caravaggios Denial of Saint Peter is objectively beautiful that its beauty is timeless and its status as a masterpiece isnt merely a function of ideology then you already share one of my basic assumptions.

Finally, the book doesnt champion this or that style, art form or school of criticism. I have my own tastes, of course, and these will seep through the arguments from time to time. But you wont find in the book any curmudgeonly opposition to new forms, still less populist disdain for art that isnt readily accessible or too abstract. What I take issue with is the veneer of faux-complexity and inaccessibility that masks a poverty of good ideas. I believe, after the great art historian and populariser E. H. Gombrich, that it is possible to achieve artistic perfection within any style. What I long for is art in any medium or style that reflects formal rigour and intellect along with genuine mystery and individuality. I suspect you seek the same.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The New Philistines:»

Look at similar books to The New Philistines:. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The New Philistines: and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.