On a grey day the larkspur looks like fallen heaven... and when there is grey weather in our hills or grey hairs in our heads, perhaps they may still remind us of the morning.

G.K. CHESTERTON, THE GLORY OF GREY

In my diary of August 1989, I noted the first thing that struck me on setting foot in the United Kingdom was the oppressively low grey sky. In my youth I couldnt wait to get back to the vast open blue canopy over Australia. A country with no lid. A young nation with a future, unbound by the past. In August 2016, I felt a cosy snugness beneath this low ceiling of soft grey on arrival in the Old Dart. Perhaps age had something to do with it. This time around I had my own long history. I was something of a relic, with a lot of future behind me. I had much in common with Britain.

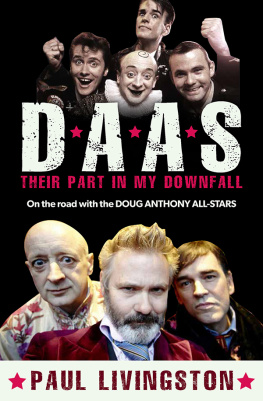

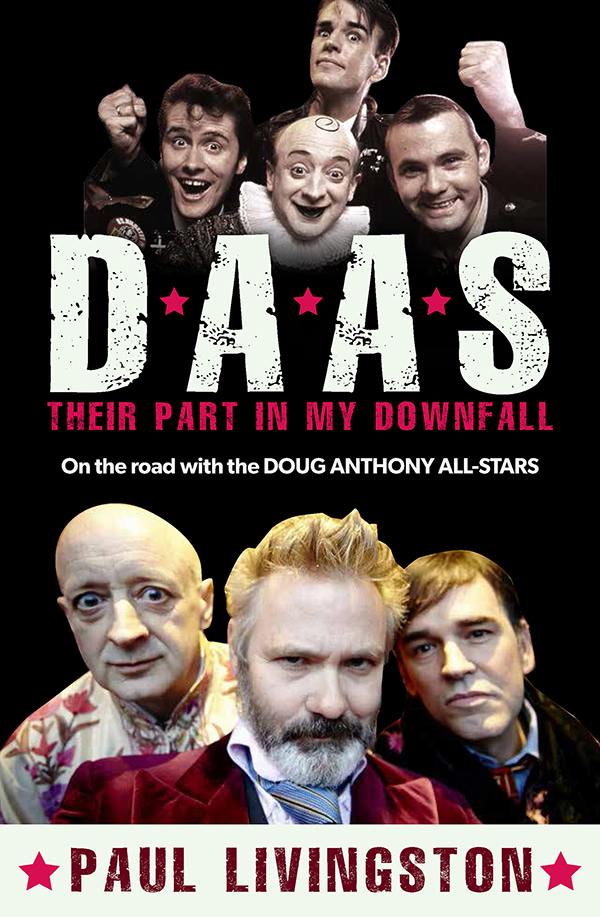

True to form, I boarded our flight to London nursing an impressive head cold. Heres a tip: if you are going to be ill on a twenty-three-hour flight, business class is the way to travel. From the limousine pick-up to the upper deck of the Qantas Airbus A380-800, I was addressed by name, fed, pyjamaed and tucked into my private pod. As I reclined in all the comforts of someone elses home, I was fully aware that it was twenty-seven years to the day since I boarded that Thai Airways flight on 31 July 1989 en route to London with Mark Trevorrow on our mission to support the Doug Anthony All-Stars, where we suffered through our own little hell of shared influenza and chain-smoking bogans. This time I was travelling bogan-free. Tim Ferguson, Cameron P. Mellor and Paul McDermott were further towards the business end of business class, but I was not complaining; I had never felt less harried while feeling so abysmally ill.

My affliction also deflected my mind from a feeling of dread that had been building for some time. What on earth were we doing? Returning to a festival once owned and conquered by the Doug Anthony All-Stars for almost a decade, yes but that decade was decades ago. And from all reports the festival had moved on and grown to epic proportions. The 2015 Edinburgh Festival Fringe boasted 50,459 performances of 3,314 shows in 313 venues.

More than twenty years had passed. Memories are short, as are most comedy careers, and while D.A.A.S. had made their mark at the time, their continued individual success and careers in Australia were all but invisible to the Brits. The All-Stars were about to appear out of the blue or the grey, to be more precise.

Frank Woodley recalls his attempted glorious return to Edinburgh in 2001, almost a decade after winning the coveted Perrier Award.

I remember giving out free tickets on the Royal Mile and saying to this girl, Look, theyre free tickets, we must at least be alright, because we did win the Perrier Award once, and she said, Oh? When did you win it? And I said 1994 and she laughed in my face. She just went, Oh right, like in ancient times.

Tim Ferguson had no doubt the former D.A.A.S. army of supporters would emerge from the woodwork and that this current incarnation would attract a new audience. I had my reservations. Its what I do best. I envisaged D.A.A.S. disappearing into a mire of performers half their age, hungrier for fame and much less physically repugnant than the current line-up. To my mind we were taking a used Holden Camira to a Formula One Grand Prix, or a penny farthing to the Tour de France.

Our business-class status came crashing down on arrival at Heathrow, where, after twenty-three hours travelling with luxury all over our laps, we were to catch a domestic flight directly to Edinburgh. A packet of Corkers Crisps and a cup of tepid tea with milk squeezed from a plastic tube was offered, and an inability to connect the fuselage to the terminal on landing had us held on board for longer than the flight. Eventually a set of stairs was procured, but this was of no use to Tim, of course. (Our production manager, Samantha Kelly, arrived twenty-four hours later with a similar tale. In this case the pilot waited forty minutes on the tarmac before opening the cockpit window and yelling to ground staff, Will some bastard please get us some stairs?!) Our heads were no longer in the clouds and our feet were firmly on Scottish ground.

They needed to be, as many of the streets of Edinburgh are cobbled, especially in the Old Town, where we were staying. Cobblestones, while quaint, are nothing more than an excuse for replacing a perfectly paved road with an uneven brick wall, and in no way suited Tim Fergusons state-of-the-art set of wheels. It was clear a heavy-duty wheelchair would need to be acquired if Tim were ever to leave the hotel and make the journey to The Pleasance, the venue where D.A.A.S. had made their first big splash, a mere few hundred metres by cobbled road.

But this was not The Pleasance of 1987. In those days it was hardly more than a courtyard surrounded by a couple of small theatre spaces. It has somewhat enlarged in the intervening years and is now home to a hive of venues, from the fifty-seater Pleasance Cellar to the seven-hundred-and-fifty-seat Pleasance Grand, the entire complex delivering over two hundred performances per day.

The All-Stars venue was the Pleasance Forth, with a seating capacity of two hundred and fifty.

In the past, venues such as The Pleasance and the Gilded Balloon were the Fringe favourites for up-and-comers; nowadays many of the acts in these prime venues are corporate-sponsored, and an unknown kid from the backwaters of Australia i.e. Richard Fidler would have a much harder time landing a gig sight unseen. Many first-timers now debut their efforts at what has become known as the Free Fringe Festival, the Fringe within the Fringe. Beginning around 2004, small rooms, pubs and the like were opened to performers with no venue hire charge and no admission price. The audience members are free to make a donation following the show if they wish.

This scenario was perhaps inevitable in view of the prohibitive costs of performing in Edinburgh for an unknown entity. Ive known performers who have mortgaged their homes to follow the dream of Edinburgh Fringe success. These free venues have taken over from traditional busking. Working the street was not only bread and butter for performers like D.A.A.S. in the eighties and nineties, but a sure-fire way to win fans and sell tickets. As in most parts of the globe, in Edinburgh busking has been formalised, legalised and amplified. A visit to The Mound in the centre of Edinburgh, where the Dougs once attracted large crowds along with various other young hopefuls, like Eddie Izzard has now become a space for professional busking acts. You know the type: the tricycle-riding, fire-eating cat jugglers with deafening sound systems and microphones. To busk on The Mound these days you need to audition, be granted a licence, then book in a time. Hence the growth and popularity of the Free Fringe.

Having once secured a venue, drawing attention to your show is the next hurdle. Posters cover the city walls. Smaller acts with A4 flyers appear as postage stamps next to the billboards of the big-name acts. Thanks to Al Murray and Avalon Promotions, sizable D.A.A.S. posters were spread across town. Al is a true believer in the D.A.A.S. cause, and I have no doubt it meant as much to him to have the boys appearing at the Fringe again as it did to Tim Ferguson and Paul McDermott.

I earlier warned that performing at the Edinburgh Fringe after 10 pm can be lethal for an act without song, dance or the ability to intimidate and dominate.