PREFACE

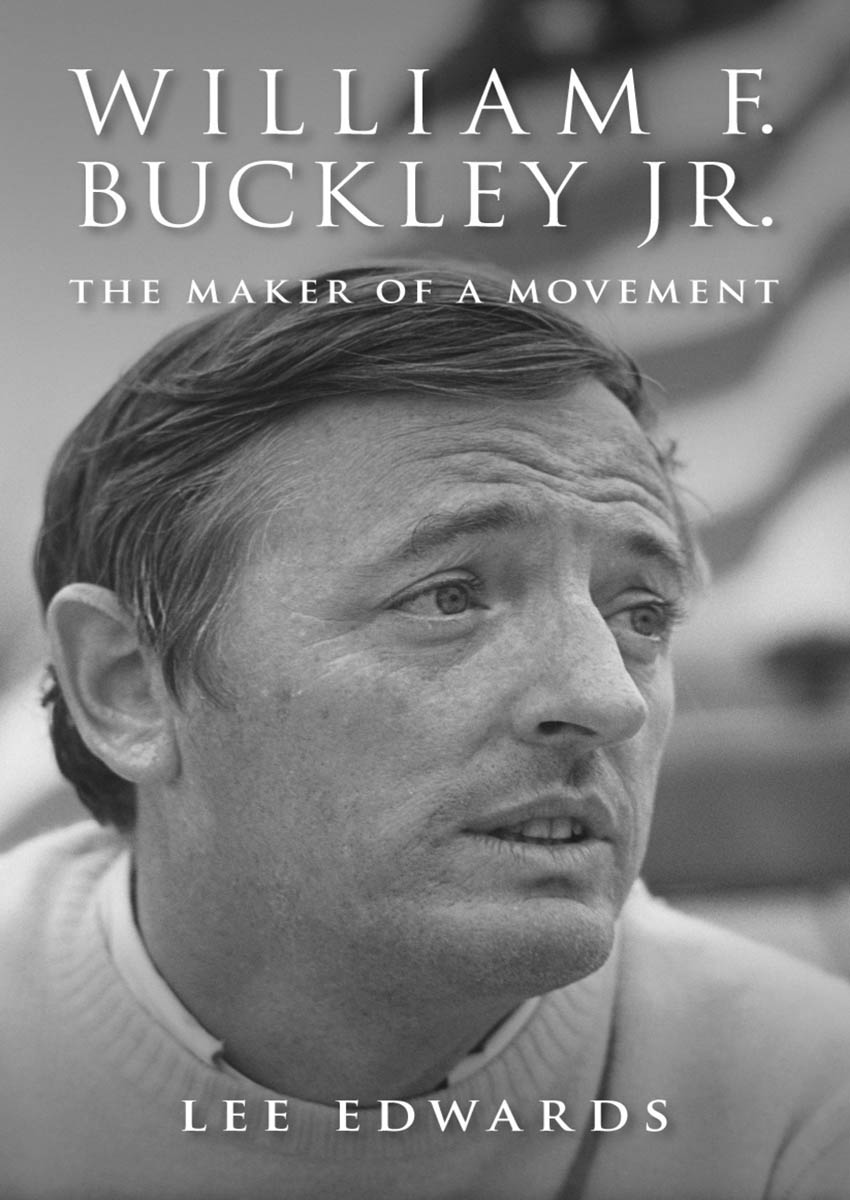

They came from Washington, D.C., New York City, and Los Angeles, as well as places far from the centers of power. They were worldly diplomats and influential commentators, powerful politicians and popular actors, public intellectuals and legendary entrepreneurs, bestselling writers and quiet scholars. They were conservatives, libertarians, and liberals; believers and atheists; young and old; high society and Middle American; white, black, and beigea panorama of twenty-first-century America. They came from Harvard and Yale, Hillsdale and Grove City, Notre Dame and the University of Chicago. They filled New Yorks St. Patricks Cathedral that early April morning as they raised their voices in praise of an extraordinary man, William F. Buckley Jr., who had died as he had lived, at his desk, writing.

George Weigel, the author of an illuminating biography of Pope John Paul II, said that Bill Buckley was one

In his St. Patricks homily, principal celebrant Rev. George W. Rutler explained that Bill Buckleys first formative academy had been his fathers dinner table, where he was taught that the most important things in life are God, truth, and beauty. Buckley adamantly opposed Communism all his life not just because it was a tyranny but also because it was a heresy. His categories, Father Rutler said, were not Right and Left but right and wrong.

Nicholas Lemann, a discerning liberal and dean of the Columbia University School of Journalism, said that during the Reagan administration the 5,000 middle-level officials, journalists and policy intellectuals that it takes to run a government were deeply influenced by Buckleys example. Some of them had been personally groomed by Buckley, and most of the rest saw him as a role model.

They had been shaped by the mighty stream of words that flowed from Bill Buckleys Royal typewriter and then PCa Mississippi River of words. Christopher Buckley, Bill and Pat Buckleys only child, recounted at the memorial mass how he had gone to the Sterling Library at Yale University to inspect his fathers papers. They totaled 248.8 linear feet, higher than the spire of St. Patricks. That did not include the 6,000 newspaper columns, 1,504 Firing Line television programs, and some fifty-five works of fiction and nonfiction.

Christopher leavened his remarks with a wry humor that would have pleased his father and that delighted the

Searching for an epitaph, Christopher recalled that his father once gave an interview to Playboy magazine. Asked why he had agreed to appear in so unconservative a publication, the elder Buckley replied, In order to communicate with my sixteen-year-old son. At the interviews end he was asked what he would like for an epitaph, and he replied, I know that my Redeemer liveth. Only Pup, Christopher said, could manage to work the Book of Job into a Hugh Hefner publication.

He ended by quoting from Robert Louis Stevensons Requiem, one of Bill Buckleys favorite poems:

Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I lay me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

Here he lies where he longd to be;

Home is the sailor, home from the sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

In the defiant mission statement in the first issue of National Review, Buckley famously wrote that his magazine would stand athwart history, yelling Stop. But, said Michael Barone, editor of the definitive Almanac of American Politics, Buckley and National Review did more than yell Stop! at history; they turned it around, first of all by establishing a coherent and respectable conservatism. Ideas and words have power, Barone said, and no one has shown more joie de vivre in deploying the power of ideas and words than William F. Buckley Jr.

In his St. Patricks eulogy, Henry Kissinger, the former secretary of state and an old friend, reminded the audience that Bill Buckley was not a utopian but a Burkean. I believe neither in permanent victories nor in permanent defeats, Buckley would say, but he did believe in permanent valuesand striving to preserve them.

We must do what we can, Buckley once wrote Kissinger, to bring hammer blows against the bell jar that protects the dreamers from reality. And then came this typically sinuous sentence: The ideal scenario is that pounding from without we can effect resonances, which will one day crack through to the latent impulses of those who dream within bringing to life a circuit which will spare the republic.

Shifting from the philosophical to the personal, Kissinger revealed how much Buckleys friendship had meant to himas it had to so many. When things were really

In the weeks following his death on February 27, 2008, the encomiums poured forth.

He is irreplaceable, remarked radio talkmeister Rush Limbaugh, who described Bill Buckley as his greatest inspiration from the age of twelve, when he read his first Buckley column in the local St. Louis newspaper. Limbaugh recalled that when he was invited to an editorial dinner at Buckleys Park Avenue home, he had his driver go around the block a couple of times while I built up the courage to actually enter the place.

Before Buckley, wrote William Kristol, editor of the neoconservative Weekly Standard, there was no American conservative movement. There were interesting (if mostly little-known) conservative thinkers. Plenty of Americans had conservative inclinations and sentiments. But Buckley created conservatism as a political and intellectual movement.

He united the fragments of American conservatism, wrote Michael Kinsley, founder of the liberal website Slate, and paved the way for Goldwater and then Reagan.

Without Billif he had decided to become an academic or a businessman or something else, said Hugh Kenner, a biographer of Ezra Pound and a frequent

Facing him, wrote Christopher Hitchens, the arch-liberal writer and militant atheist who had often appeared on Firing Line,

one confronted somebody who had striven to take the cold out of the phrase Cold War; who had backed Joseph McCarthy, praised General Franco, opposed the Civil Rights Act, advocated rather than merely supported the intervention in Vietnam, and seemed meanwhile to embody a character hovering somewhere between Skull-and-Bones and his former CIA boss Howard Hunt. On the other hand, this was the same man who had picked an open fight with the John Birch Society, taken on the fringe anti-Semites and weirdo isolationists of the old Right, and helped to condition the Republican comeback of 1980. Was he really, as he once claimed, yelling stop at the locomotive of history, or was he a closet progressive?

It is a provocative suggestion, but the late Tim Russert, then the moderator of NBCs Meet the Press, rightly emphasized that Bill Buckley was a conservative and proud of it. He understood the rhythms of history, said Russert: that there was a race worth running in 1964 with Barry Goldwater that would probably be unsuccessful but it would lay the groundwork for a successive takeover of the Republican Party, and the White House, to wit Ronald Reaganand he was right.

Not everyone was so complimentary, even within the conservative movement.

Christopher Westley, a professor of economics and contributor to the libertarian website

The prominent paleoconservative academic Paul Gottfried quoted anti-immigration advocates Peter Brimelow and Larry Auster, who argued that Buckley had become the captive of a leftward-moving American culture. Gottfried insisted that Buckley had handed over American conservatism to neoconservative adventurers from the Left, making neoconservatism the only permissible form of thinking on the right.