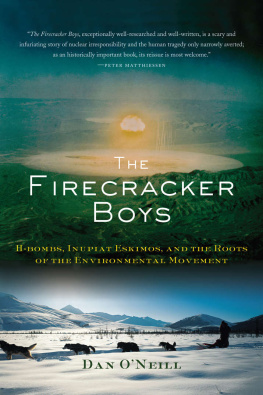

THE FIRECRACKER BOYS

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 255-1514, or e-mail .

This book was previously published by St. Martins Press in 1994.

Designed by Timm Bryson

Set in 10 point Weidemann Book

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ONeill, Dan (Daniel T.)

The Firecracker Boys: H-bombs, Inupiat Eskimos and the roots of the environmental movement / Dan ONeill.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-465-09752-4

1. Project Chariot. 2. Hydrogen bombTestingAlaskaThompson, Cape (North Slope Borough) 3. Nuclear excavation. 4. Nuclear weaponsUnited StatesTestingHistory. 5. Antinuclear movementUnited States. 6. Teller, Edward, 19082003. 7. InupiatAlaskaHistory20th century. I. Title.

UG1282.A8O39 2007

621.48dc22

2007030702

To the memory of my father

John Terence ONeill

The author acknowledges with gratitude the support of the Alaska Humanities Forum, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

[There was] a general atmosphere and attitude that the American people could not be trusted with the uncertainties, and therefore the information was withheld from them. I think that there was concern that the American people, given the facts, would not make the right risk-benefit judgements.

Peter Libassi, Chairman, Interagency Task Force on the Health Effects of Ionizing Radiation

I know of no safe repository of the ultimate powers of society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion with education.

Thomas Jefferson

CONTENTS

No truly primitive group could exist under such conditions. Only by means of a highly complex technology and through a highly developed knowledge of natural phenomena could human beings penetrate the Arctic.

Helge Larsen and Froelich Rainey, Arctic archeologists

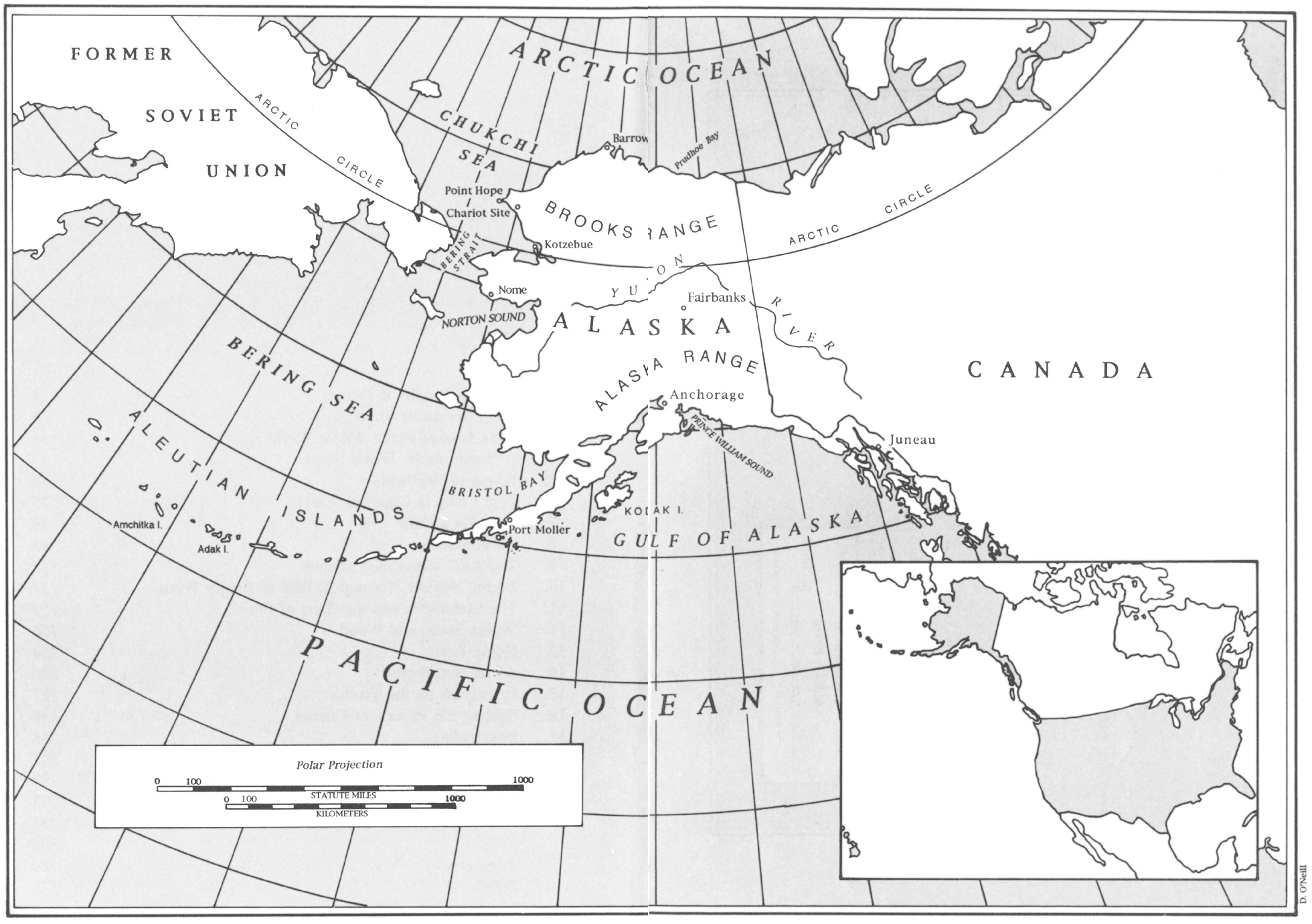

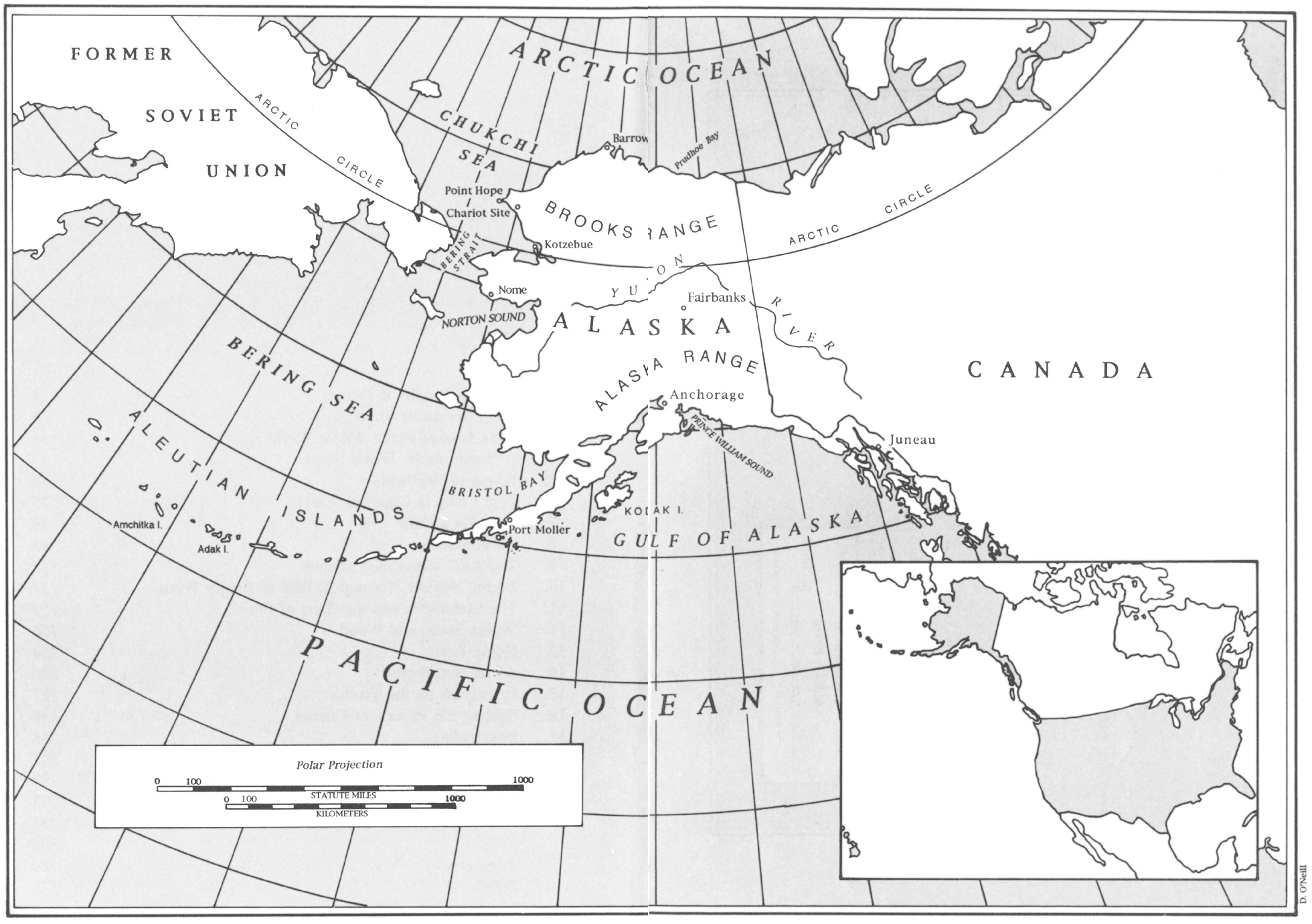

In the extreme northwest corner of the North American continent, in the region of Bering Strait, prehistoric Inupiat hunters discovered a spit of land jutting twenty miles into the Chukchi Sea. It pointed like a finger back across the water to the peoples ancestral homeland, Asia, just 160 miles away. They called the place Tikigaq, the Inupiaq word for forefinger.

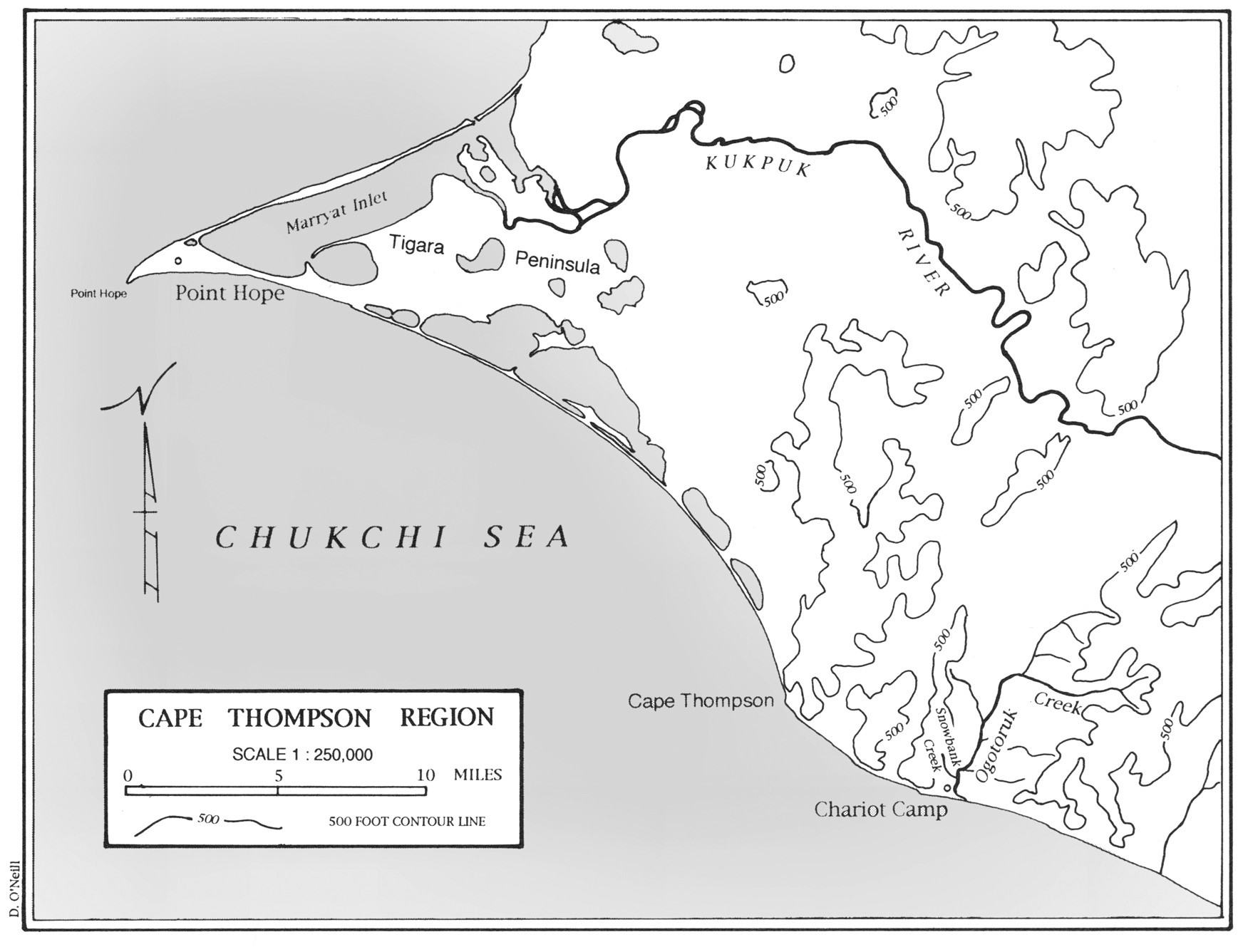

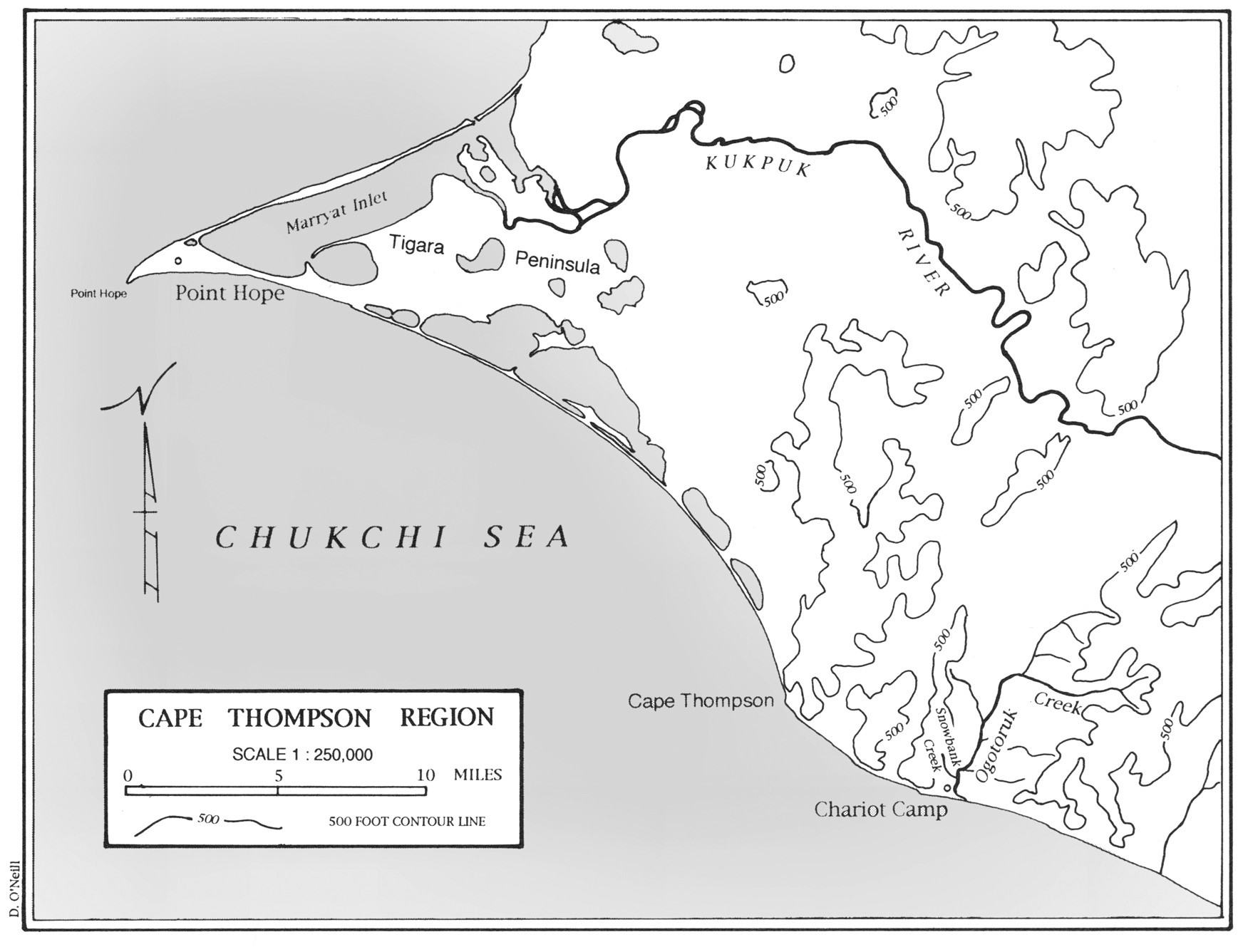

The peninsula was an ideal place to intercept migrating sea mammals. From here the Inupiat hunted walrus, seals, and polar bear. They hunted the small white whale called beluga, and ugruk, the bearded seal. They collected the eggs of nesting seabirds from the inland cliffs near a little stream they called Ogotoruk. Eventually, they would load flint-pointed harpoons into ugruk-skin boats and chase, strike, and land fifty-ton bowhead whales. At Tikigaq, they built semisubterranean houses employing what few materials existed in a place a hundred miles from the nearest tree: whalebones and driftwood for the arching structural ribs, and slabs of sod stacked up igloo-fashion to form a covering. As wind and rain smoothed the contours, and sod and flowers sprouted again, the settlement looked like a hummocky patch of grassland, a green rejoinder to the surrounding blue, rolling sea.

That was the summer picture, anyway. In winter, the Chukchi Sea freezes. The spit stands only a few feet above the sea ice, and both are covered indiscriminately by hard-packed, windblown snow. It is hard to tell where the land leaves off and the sea begins. To the extent that Tikigaq looked like a village at all, it must have seemed to be one adrift on the sea ice, twenty miles from shore, unsheltered from the strong winter winds, more than a hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle.

Most oral history accounts agree that the early inhabitants of the region around Tikigaq organized themselves into a social system akin to a modern nation. They occupied a precisely defined territory, defended it, and, like the citizens of modern states, were not averse to expansionist forays. Sometimes the Tikirarmiut, as they called themselves, penetrated several hundred miles into neighboring dominions. In time, they became the largest and most powerful society in northern Alaska, the aristocrats of the Arctic, as one writer has called them. By the late 1700s, their territory included a stretch of coast from Icy Cape, 200 miles to the north, to Kotzebue Sound, 200 miles to the south.

It was during this time, in 1778, that Capt. James Cook became the first European to sail up the Alaska coast, through Bering Strait and into the Chukchi Sea. But, though he explored all the way to Icy Cape, he missed the low Tikigaq spit. Shortly after Cooks voyage, around the turn of the nineteenth century, the Tikirarmiut lost a decisive battle with a people on their southern frontier and may have lost half their entire population. It is likely that many of the best hunters died and a period of starvation followed. Europeans first encountered Tikigaq during this period of instability. In 1820, Glieb Semenovich Shishmarev of the Russian navy saw the settlement from some miles offshore. Sailing by without landing, he named the point Cape Golovin in honor of a fellow captain in the Russian navy.

The next Europeans to glimpse Tikigaq reenacted the discovery and, for the second time, the most prominent features of the Eskimos homeland were renamed, this time in honor of Englishmen. Capt. F. W. Beechey sailed HMS Blossom into the Chukchi in 1826 and closed on a high bluff, which he named Cape Thomson (later written Thompson) after Deas Thomson, a commissioner of the British navy. Putting ashore, Beechey became the first outsider to encounter the Tikirarmiut when his party was met upon the beach by some Esquimaux who eagerly sought an exchange of goods. Very few of their tribe understood better how to drive a bargain than these people. Beecheys account describes a robust people above the average height of Esquimaux: the tallest man was five foot nine inches, the tallest woman five foot four inches. All the women have tattooed upon the chin three small lines... all the men had labrets [lip ornaments]. The Englishmen found the natives to be very honest, extremely good natured, and friendly.

After visiting a small encampment near the base of Cape Thompson, Beechey ascended the promontory. From its vantage he discovered low land jetting out from the coast to the W.N.W. as far as the eye could reach. As this point had never been placed in our charts, he wrote, I named it Point Hope, in compliment to Sir William Johnstone Hope. The next morning Beechey sailed away to the west to trace the extent of the low point he had seen from Cape Thompson. On nearing its tip, he saw a forest of stakes... and beneath them several round hillocks. The stakes were drying racks on which chunks of dark purple seal meat hung and skins lifted in the steady breeze. Other racks, made from the jawbones of whales, supported

Next page