Table of Contents

DEDICATION

For Clay and Julie

FOREWORD

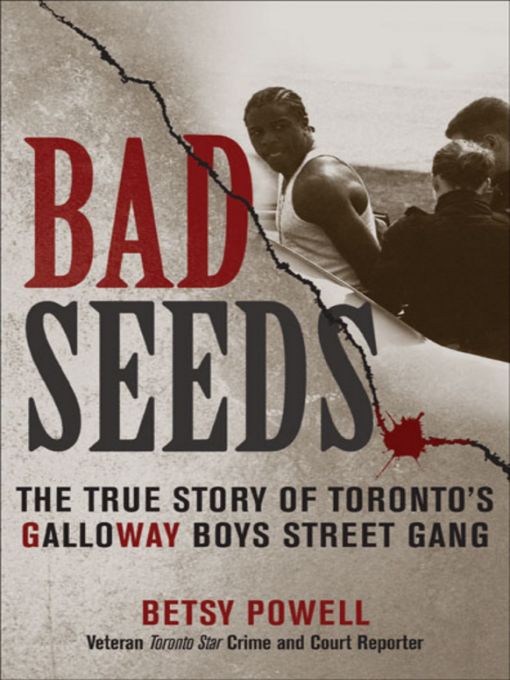

When my friend Betsy Powell told me she was writing a book about black street gangs in Toronto, I thought: Its about time. For too long, people in this city, in this country, have lived in blissful ignorance. Gangs were an American phenomenon. Black ghettos were an American problem. Not here. No way.

Sure, Canadians know there are gangs: Mafia, bikers, Asian, aboriginal, black. But its not as if there are drive-by shootings in Rosedale or Forest Hill, Westmount or Shaughnessy. Sure, Canadians know there are racial tensions in their cities. But its not as if there are altercations on Bay Street, or St. Catherine Street, or Robson Street. As long as the gangsters are killing each other in their own neighbourhoods, who cares? Its only when they bring their guns downtown that anybodythe politicians and media that fuel outbreaks of hysterianotices.

In Toronto, starting in the early 1990s, there were episodic eruptions: the race riot that the white power structure insisted was not a race riot; the shotgun blast fired by a black robber, killing a young white woman sitting in a trendy caf; the 15-year-old white girl gunned down by black kids in a shootout on a busy downtown street. These were the stories that created the boldest headlineseach time young blacks broke the peace in Toronto the Good.

But this book takes a look at Toronto the Bad, the separate society that exists across an unmarked border, where poverty, drugs and guns create an explosive mix, where people live in fear in their neighbourhoods, where a generation of Canadians has been lost to the lure of crime, where clueless cops sometimes crash the party, and oblivious politicians show up only during an election campaign.

This is the backdrop for Bad Seeds. But this is not some thumb-sucking dissertation on the roots of poverty or black alienation, though thats a part of it. It is a true-crime story of how one senseless shooting eventually blew the lid off a shocking spike in gang warfare in Toronto in the early years of the 21st century. It is a sometimes touching, often frightening, tale with real heroes and real villains.

Youll meet Brenton Charlton, a young man with a future, murdered in a case of mistaken identity, and his friend Leonard Bell, who still lives with bullets in his body. Youll meet Tyshan Riley (pictured on cover), the scariest kid on the block, who rises to the top of his unlawful and immoral world, gaining power with the gun to feed his insatiable appetite for money and sex. Youll meet the man who brought him down, Roland Ellis. He sold drugs with Riley and subscribed to much of his criminal code, but resisted the seemingly random violence that Riley unleashed in their community.

Youll meet the cops who turned Ellis into a witness, finally cracking the case of the shooting of Charlton and Bell, while employing an extensive network of wiretaps to nail most of the Galloway Boys gang. On these taped conversations, youll hear the nearly incomprehensible lingo of the streets, where gang members are known only by a strange assortment of nicknamesone after a bear in a Disney movieand give pet names to their guns.

To make sense of all this, Betsy sifted through hundreds of hours of evidence, from wiretaps to police interviews with suspects and witnesses. As a reporter for the Toronto Star, she covered the marathon preliminary hearing that ultimately resulted in murder charges against Riley and two cohortsand the murder trial that followed. She got to know the families of the victims and the accused, especially Charltons mother, Valda Williams, who lost her only son.

Betsy also often went into their communitythe once-sleepy suburb of Scarborough, known as Scarberia and later called Scarlemto talk to people who knew Riley and Ellis and the rest of the Galloway Boys when they were growing up. In many cases, these citizens were afraid to speak if their names would be attached to their words.

When Betsy first approached me about working with her on this project, I thought I might bring a certain perspective. As an American who arrived in Toronto in 1975, I had seen some of the signs of the times earlier than my Canadian friends and colleagues. Growing up in New York in the 1950s and early 60s, I had watched the city slide into the chaos of random violence and racial hatred. As a reporter in New York in the late 60s and early 70s, I had covered riots and slaughter in the streets. When I came to Canadafirst Vancouver, then Montreal and finally Torontoas a correspondent for United Press International, I found an oasis of peace and civility. But I brought my American wariness with me.

I recall standing on a subway platform at Union Station one night with a fellow journalist who had lived in Toronto most of his adult life. A small group of young black men huddled nearby. It was the spring of 1981, when race riots were sweeping Britain.

Its going to happen here, I told my friend.

He laughed. Youre nuts, he said.

You watch, I said.

I was wrong. But I was also right. Over the ensuing decades, crime rates rose, guns arrived by the truckload, and the Canadian security blanket became a bit tattered.

Many of the characters in this book are as creepy as any youll find in the most gang-infested neighbourhoods of Los Angeles, Chicago, Mexico City or Rio de Janeiro.

That prompted me to ask Betsy whether she feared any of the gangsters she was writing about. She told me a story about December 26, 2005:

It was a relatively quiet day in the Stars downtown newsroom. So, as the crime reporter, I worked on a feature about evidence police were using to prosecute members of a northwest Toronto gang. It was a DVD called Rapsheet and featured young black men, their faces covered with bandanas, rapping and waving guns in the air. Some of these young men were now facing charges, the police said.

Around 4:30, quitting time, I left the Star and headed up Yonge Street. It was still light, not all that cold, and I thought I might see if there was anything left from the Boxing Day sales that I probably didnt need.

When I got to Shuter Street, between Queen and Dundas, I had a weird feeling. Im not someone normally given to premonitions, but there was a sense of menace in the air. Was it coming from the clusters of young black men I saw, with their hoods raised? Or did I focus on them because Id spent the day watching a DVD of young black men waving guns around? What prompted me to cross the street? Or to consider calling the Star? To say what? That I had a feeling there was going to be trouble on Yonge Street?

At around 5 p.m. I went into the Guess store at Dundas to try on jeans. Music was thumping when I went into a change room at the back. I didnt buy anything and left the store about twenty minutes later. There were cops everywhere. People were crowded behind yellow crime-scene tape. Some were talking on cell phones, or using them to take pictures.

Jane Creba had already been taken away. Some of the other victims remained. I was back in the newsroom that nightwith others who had jumped infiling a story for the front page.

But Betsy wasnt interested in writing a book about the 15-year-old white girl killed downtown on Boxing Day, the bystander in a shootout between young black kids. It was the exception, the clich that got the medias juices flowing. She was more interested in the shooting of Charlton and Bell a year earlier, the black innocents among many black casualties. And she wanted to know more about the gangs that populated her city, the neighbourhoods where she grew up.