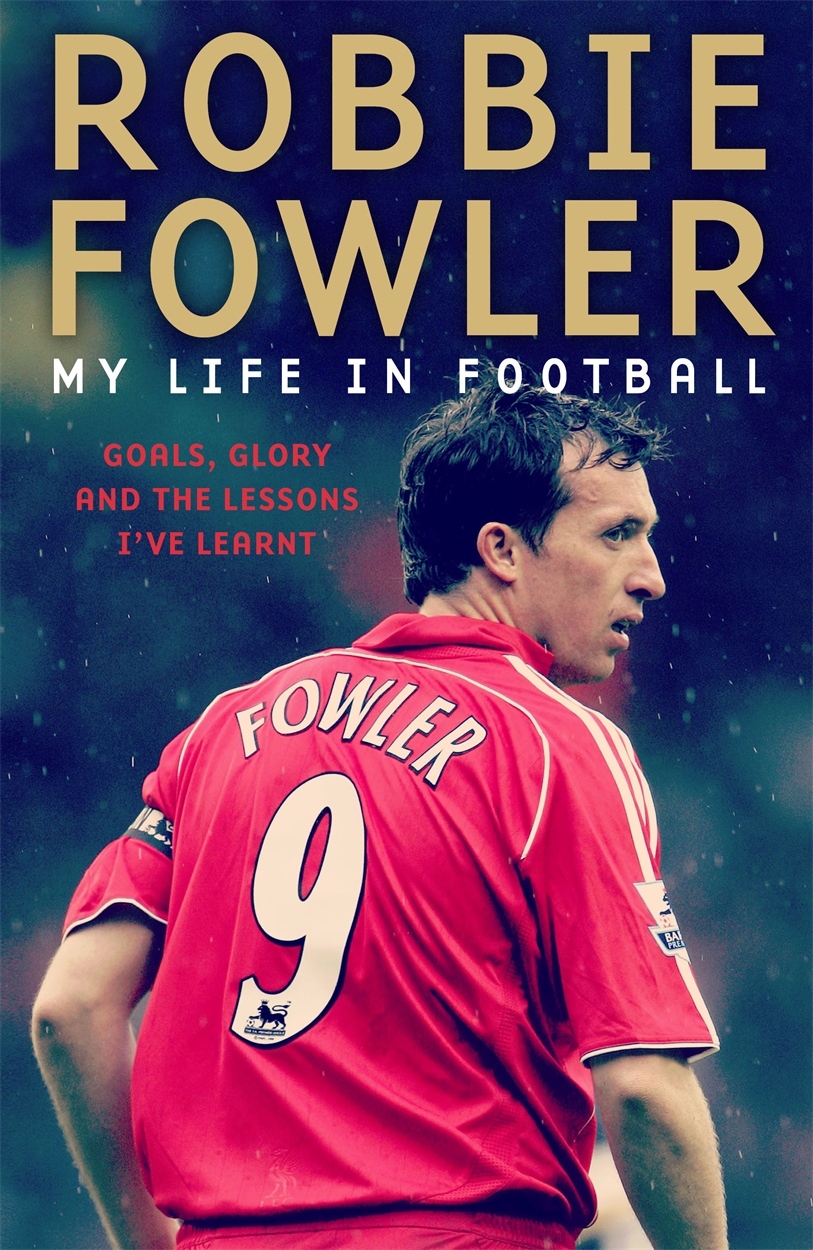

MY LIFE IN FOOTBALL

ROBBIE FOWLER

MY LIFE IN FOOTBALL

Published by Blink Publishing

2.25, The Plaza,

535 Kings Road,

Chelsea Harbour,

London, SW10 0SZ

www.blinkpublishing.co.uk

facebook.com/blinkpublishing

twitter.com/blinkpublishing

Hardback 978-1-788-701-10-5

Trade paperback 978-1-788-701-11-2

Ebook 978-1-788-701-12-9

All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or circulated in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue of this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by seagulls.net

Copyright Robbie Fowler, 2019

Robbie Fowler has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

Blink Publishing is an imprint of Bonnier Books UK

www.bonnierbooks.co.uk

This book is dedicated to my incredible family, without whose love and support I would be nothing.

My wonderful mother Marie, who gave me everything. My Dad Bobby, who I miss every day. My sister Lisa, who was always there for me. My brothers, Anthony and Scott, who kept my feet on the ground.

Special thanks to my fantastic children Madison, Jaya, Mackenzie and Jacob, who I love more than anything in the world. You four are my pride and joy and you make me smile every single day.

Thanks dont go near to expressing the love and gratitude I have for my amazing wife Kerrie my rock, my refuge and, quite simply, the love of my life; but thank you for saying Yes. I might be far away but youre all right here in my heart.

CONTENTS

24TH MARCH 1997

Its Liverpool against Arsenal in a live game at Highbury. Were both still just about involved in the title race, third and fourth respectively. It was being billed as a clash of the purists as the countrys two most attacking teams came up against each other.

Were 10 up and Mark Wright sends a speculative ball for me to chase after and I find myself leaving Tony Adams in my wake, with only David Seaman to beat. I slightly overrun the ball, giving Seaman a sniff of a chance, and he rushes out to try to smother it. I get there first, nick the ball past him, but in doing so, my momentum (and the change of direction) sends me sprawling in the box. Seaman hadnt touched me and had no intention of doing so. The referee was chasing the play from behind and from his point of view, it probably looked a stone-cold foul by the keeper.

The ref caught up with us and immediately pointed to the spot. Straight away, I jumped up and went over to him, waving my hands to say, No contact, no contact. I assured him that Seaman hadnt touched me, but hed already made his decision.

Two days later, the club received a fax addressed to me from Sepp Blatter the President of FIFA. He told me how refreshing it was that Id tried to get the penalty decision overturned.

The very next day I received a letter from UEFA, telling me they were fining me 1,000 for displaying a political slogan on my T-shirt at a previous game.

Talk about hero to zero.

This is a footballers life.

To this day people ask whether Toxteth was the making of me. Im not sure what to make of that. Up until I got my first flat in the Albert Dock I never lived anywhere else, so its not like I can compare my childhood home with another place. I grew up in a maisonette on one of the main through roads, Windsor Street, and when I was about ten or so we moved to Hughson Street, off Park Road. There was me, my older sister, Lisa, our Anthony, who was a few years younger than me, and, later on, our Scott came along.

Our Lisa was the best big sister you could wish for (and still is). She wasnt one of those bossy older siblings whos always telling you off and putting you down. Lisa was more of a mate when we were growing up, then, as we got older, she was someone I could always talk to, full of good advice. And, as much as I loved Everton, our Anthony was Liverpool mad. Born in 1980, he was getting into footy just as King Kenny was building that incredible, all-conquering team of John Barnes, Ray Houghton, Peter Beardsley and John Aldridge (and soon Anthony would soon have someone closer to home to cheer for, too!).

The world of my childhood spanned from the recreation ground on Upper Warwick Street to the youth club on Park Road. That was me, right from the first whistle a normal, outdoorsy, football-loving Toxteth lad. All my family lived in and around Liverpool 8 and I loved growing up there.

Toxteth of course became world-famous (or infamous) after the riots of July 1981 and, like a lot of inner-city areas, it has had its problems over the years. Scousers often describe themselves as North Enders or South Enders. Jamie Carragher and Steve McManaman are pure North End, but Im from the sophisticated South End of the city. Toxteth and Dingle, known to locals as Granby or Liverpool 8, is the area that stretches from the Maternity Hospital on Upper Parliament Street down past the Anglican Cathedral, all the way to the River Mersey and along as far as Princes Park. The river and the sea played a huge part in developing Toxteth as an area and as a community. From the grand old merchants villas around Belvedere Road and Princes Drive to the dense terraced streets of the Dingle, Liverpool 8 always had a mix of housing and the broadest mix of peoples Irish, Jamaican, Filipino, Ghanaian, Welsh, Nigerian, Somali All of these nations and many, many more made Liverpool 8 their home, adding a certain something to the local flavour.

The Toxteth I grew up in was a tough, busy, multicultural community tight-knit and, I suppose, a bit suspicious of outsiders. But community is what it was and is, and this is where Im from. I think what interviewers are driving at when they ask me about Liverpool 8 is this assumption that the place was so rough and so poor that I must have been desperate to get out. Far from it! I had a dead normal, happy childhood. At no stage did I feel impoverished or neglected, or whatever. I always had the best footy boots, always had a smile on my face, and in every way I can think of, I was just another normal kid who lived for football. But where those reporters are spot on is that the streets I grew up on, and their equivalent in London, in Manchester, in Belfast, Newcastle or Glasgow time and time again, these are the streets that breed footballers. You look at Raheem Sterling or Dele Alli today; Steven Gerrard and Wayne Rooney; Gazza, Paul Ince, Alan Shearer from my time; Kenny Dalglish, Ian Rush, going all the way back to Jimmy Johnstone and Georgie Best Theres a pattern there, isnt there? These are all working-class boys from the inner-city streets or sprawling new towns and council estates and they all badly, badly want to be footballers. Theres no Plan B to fall back on. They want it, and they want it like mad.

That was me, too: inner city born and bred, and football mad. I dont know if theres such a thing as a born footballer, but footy was pretty much all I ever thought about and the only thing I did from the day I could walk. Some might say I never got much faster than those toddling days, but boy, did I want to play! As it happens, I did have a bit of trouble with my mobility as a kid. Its a common enough thing, but I was born with a clicky hip, which is just a minor design flaw that, these days, would be spotted at birth and treated with a correctional brace. Mum took me to see various doctors and consultants over it, but the consensus was that nature has a way of righting these things. I actually grew up walking with a slightly uneven gait for those first few years, though it sorted itself out before primary school. I also had asthma as a kid but neither that, nor my hip, could keep me indoors. There was the Rec, a patch of land right opposite our maisonettes it was turned into an all-weather pitch when I was about eight and I used to be out there with a ball, morning, noon and night. I truly believe that everything that happened later can be traced back to that little scrap of green (or brown, when the rain came down in the winter) turf. Over the years, Ive spoken to a lot of players who come from a similar background and they all have a similar tale to tell. Each and every one of us was out until all hours with a ball glued to our feet, playing wherever and whenever we could, until there was no one left to play against or with. I remember this feeling of sadness, almost akin to betrayal, when the last of my pals said they had to go home. I lived right opposite the rec, so there was always my mum or my sister or someone to keep an eye on me but I never wanted to come in.