In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

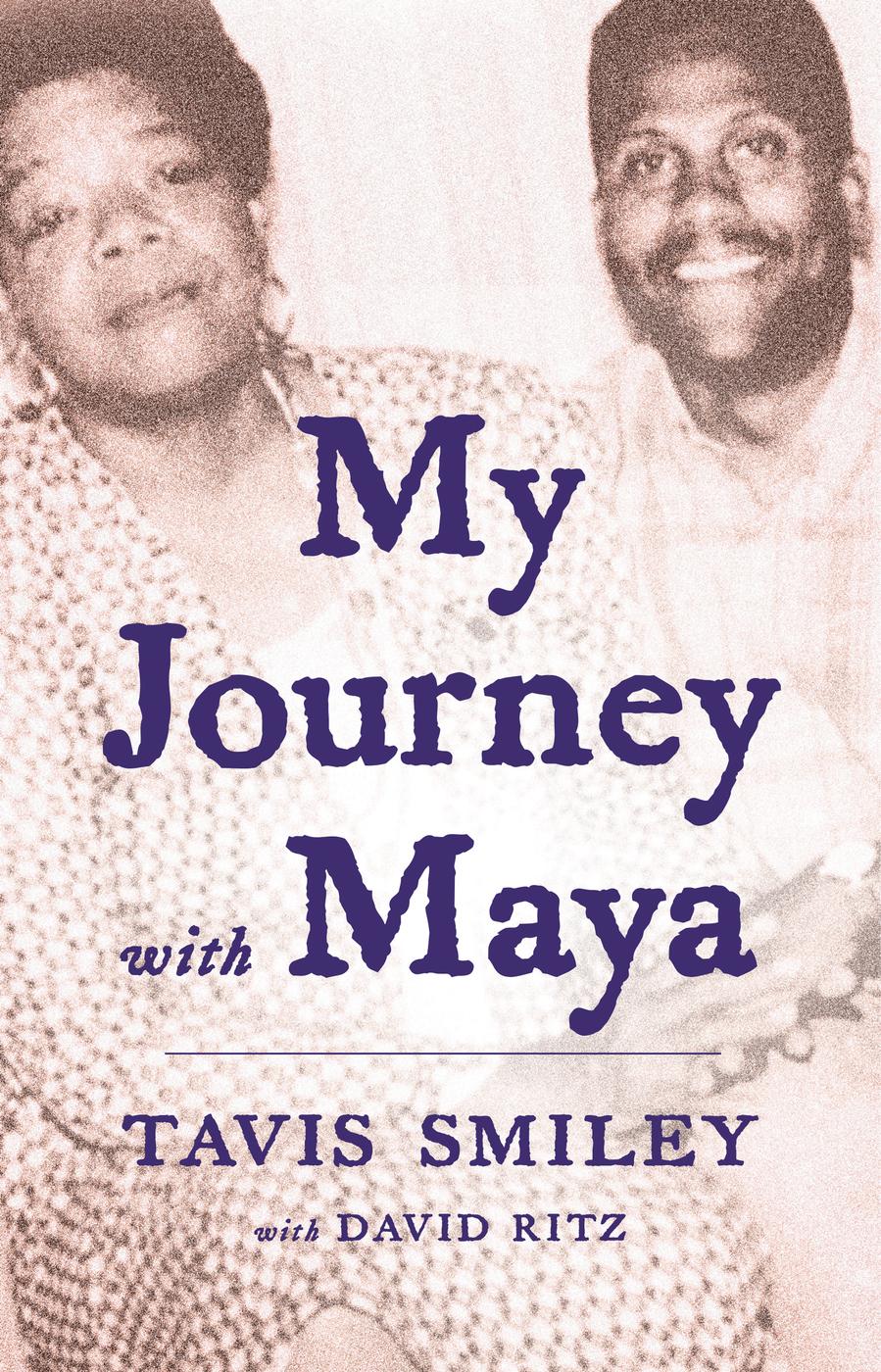

Joyce Smiley, Daisy M. Robinson, Adel Smiley, Eula Collins,

Irene West, Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou and I shared a friendship that I count as one of the great blessings of my life. As you will soon see, she appearedand kept appearingexactly when my spirit required repair. I do not consider those appearances coincidences but rather precious gifts.

The aim of this book is to share those gifts with you.

Its a lesson Maya Angelou taught me. Maya was all about sharing. In her writing and public appearances, her soaring spirit attracted legions of loyal fans. But without minimizing those literary and televised encounters, I have to say that the personal experiencethe one-on-one, face-to-face meeting with Mayaheld a power all its own. Those are the meetings, whether during our journey to Africa or in her homes in Harlem and North Carolina, that I seek to bring to life in this memoir.

I do so to honor my dear friend and, to the best of my ability, give you what she gave mewords and attitudes that invigorate the soul. Mayas great mission was to demonstrate how courageous love can heal even the deepest wounds. She taught me about bravery, about listening, about language.

The ideas expressed to me were ones she had sharedand would continue to sharewith many others. She was remarkably consistent in expressing her loving vision and strategies for spiritual survival. Maya freely spread her sagacity to as many people as possible and in as many forms as possible. I was only one of many who had the good fortune to sit by her side and glean her wisdom.

When we met, I was in my twenties and Maya was in her late fifties, a strong and vital presence. During the course of our twenty-eight-year dialogue, we both faced enormous challenges and went through life-altering changes. Up close, I was privileged to see how Maya responded to those challenges and changes. And most poignantly, I was able to see how she approached what many consider the greatest trial of all: impending mortality.

Mayas immortality rests in the beautiful body of work she left behind. Undoubtedly she will be discovered and rediscovered by generations to come. Just as Paul Robeson is remembered as the greatest Renaissance man in the history of black Americaathlete, actor, activist, scholar, singer, lawyerI believe Maya will be remembered as black Americas greatest Renaissance womandancer, poet, actor, screenwriter, memoirist, director, lyricist, activist.

A brief note about the form of this book:

Maya Angelou was blessed with an extraordinary voice. By quoting her, I strive to convey the haunting beauty and lilting musicality of her storytelling. She told and retold many stories, some of which youll read here; other conversations I recount were private and have never appeared anywhere else. In re-creating her voice for this text, I have based quotations on the copious notes I took during our private encounters, the transcripts of our many public conversations, my best recollections, and the complete written works of Maya Angelou.

I hope that by writing down for you Mayas impact on my life I can shed new light on her luminous character. I miss her every day, and if this book lets you see her, hear her, and feel her spirit, I will be gratifiedsatisfied that I have done what, in both word and deed, Maya urged us all to do:

Pass on the love.

My life was filled with purpose.

But nothing could have prepared me for what I was about to do. I had a letter to deliver to Maya Angelou. It was the early 1990s. In my senior year at Indiana University, I had sought out and miraculously persuaded Tom Bradley, the first black mayor in the history of Los Angeles, to hire me as one of his many assistants. It didnt matter that my job assignments were mundanefilling in for the mayor at low-level ribbon-cutting ceremonies, accompanying the mayors wife to her medical appointments, writing countless administrative memos. I was thrilled to be working for a dedicated and powerful public servant.

Growing up in a trailer park in rural Indiana, a black kid in a white world, I had gravitated toward mentors and public servants such as Kokomo city councilman Douglas Hogan and Bloomington mayor Tomilea Allison. I liked the way they gave voice to the voiceless. I, too, wanted to champion the downtrodden. Martin Luther King Jr. was my spiritual and political hero, and I wanted to do all I could to right societys wrongs.

It wasnt until college that I had the chance to sit under the teachings of black instructors. In my first course in Afro-American studies, Professor Fred McElroy lectured on the subject of two women whose writing impressed me deeplyToni Morrison and Maya Angelou. So when Ms. Morrison was scheduled to lecture at the university, I was the first to show up and take a seat in the front row. She spoke with rare eloquence. She spoke not only of the long and hallowed history of African American expression in literature, art, music, and dance but also touched upon European philosophy, Freudian psychology, and Greek mythology. Her intellectual discourse had me reeling. So eager was I to engage her in dialogue that the moment she invited questions, mine was the first hand to pop up. I asked her about her careercertainly nothing profound. I just wanted to be part of the discussion.

I couldnt blame Ms. Morrison for summarily dismissing me. She rolled her eyes, sighed, and gave a short, curt response. Her disdain was understandable. If I didnt have a real question to ask, why bother? Why waste her time and the time of this assembly?

I had no follow-up. I quickly retreated, searching for a hole in the floor through which to disappear.

That marked my first experience with a world-famous intellectual.

Several years passed. I was working in Los Angeles when Mayor Bradley asked me to bring a personal letter of welcome to Dr. Maya Angelou, who was appearing before a philanthropic organization. Given my experience with Toni Morrison, you can understand why I was extremely cautious in my approach, to the point of being intimidated.

I reminded myself that I was only a glorified errand boy. Just hand-deliver the letter and leave.

When I arrived, the program had not yet begun. I found Dr. Angelou seated in front of fifty or sixty people. Surrounded by many admirers, she exuded dignity and patience as, one by one, she greeted her fans and exchanged a few pleasantries.

Quite correctly, I said, Dr. Angelou, its my privilege to present you with this letter from our mayor. He regrets that urgent city business prevents him from being here in person.

I understand, young man, she said. Her eye contact was intense and sustained. Youll be certain to give the mayor my warmest regards.

I certainly will.

The encounter ended there. For a second, I thought of telling her how much her memoirs meant to me; how deeply I loved her poetry; how I yearned to learn more about her relationship with Dr. King and Malcolm X. There were a million and one questions I yearned to ask. But knowing that this was neither the time nor the place, I turned and left. Besides, the mayor had me running to another event, which meant I couldnt even stay for the program.