The ole ark's a-moverin', a-moverin', a-moverin', the ole ark's a-moverin' along

That ancient spiritual could have been the theme song of the United States in 1957. We were a-moverin' to, fro, up, down and often in concentric circles.

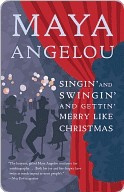

We created a maze of contradictions. Black and white Americans danced a fancy and often dangerous do-si-do. In our steps forward, abrupt turns, sharp spins and reverses, we became our own befuddlement. The country hailed Althea Gibson, the rangy tennis player who was the first black female to win the U.S. Women's Singles. President Dwight Eisenhower sent U.S. paratroopers to protect black school children in Little Rock, Arkansas, and South Carolina's Senator Strom Thurmond harangued for 24 hours and 18 minutes to prevent the passage in Congress of the Civil Rights Commission's Voting Rights Bill.

Sugar Ray Robinson, everybody's dandy, lost his middle weight title, won it back, then lost it again, all in a matter of months. The year's popular book was Jack Kerouac's On the Road, and its title was an apt description of our national psyche. We were indeed traveling, but no one knew our destination nor our arrival date.

I had returned to California from a year-long European tour as premier dancer with Porgy and Bess. I worked months singing in West Coast and Hawaiian night clubs and saved my money. I took my young son, Guy, and joined the beatnik brigade. To my mother's dismay, and Guy's great pleasure, we moved across the Golden Gate Bridge and into a houseboat commune in Sausalito where I went barefoot, wore jeans, and both of us wore rough-dried clothes. Although I took Guy to a San Francisco barber, I allowed my own hair to grow into a wide unstraightened hedge, which made me look, at a distance, like a tall brown tree whose branches had been clipped. My commune mates, an icthyologist, a musician, a wife, and an inventor, were white, and had they been political, (which they were not), would have occupied a place between the far left and revolution.

Strangely, the houseboat offered me respite from racial tensions, and gave my son an opportunity to be around whites who did not think of him as too exotic to need correction, nor so common as to be ignored.

During our stay in Sausalito, my mother struggled with her maternal instincts. On her monthly visits, dressed in stone marten furs, diamonds and spike heels, which constantly caught between loose floorboards, she forced smiles and held her tongue. Her eyes, however, were frightened for her baby, and her baby's baby. She left wads of money under my pillow or gave me checks as she kissed me goodbye. She could have relaxed had she remembered the Biblical assurance Fruit does not fall far from the tree.

In less than a year, I began to yearn for privacy, wall-to-wall carpets and manicures. Guy was becoming rambunctious and young-animal wild. He was taking fewer baths than I thought healthy, and because my friends treated him like a young adult, he was forgetting his place in the scheme of our mother-son relationship.

I had to move on. I could go back to singing and make enough money to support myself and my son.

I had to trust life, since I was young enough to believe that life loved the person who dared to live it.

I packed our bags, said goodbye and got on the road.

Laurel Canyon was the official residential area of Hollywood, just ten minutes from Schwab's drugstore and fifteen minutes from the Sunset Strip.

Its most notable feature was its sensuality. Red-roofed, Moorish-style houses nestled seductively among madrone trees. The odor of eucalyptus was layered in the moist air. Flowers bloomed in a riot of crimsons, carnelian, pinks, fuchsia and sunburst gold. Jays and whippoorwills, swallows and bluebirds, squeaked, whistled and sang on branches which faded from ominous dark green to a brackish yellow. Movie stars, movie starlets, producers and directors who lived in the neighborhood were as voluptuous as their natural and unnatural environment.

The few black people who lived in Laurel Canyon, including Billy Eckstein, Billy Daniels and Herb Jeffries, were rich, famous and light-skinned enough to pass, at least for Portuguese. I, on the other hand, was a little-known night-club singer, who was said to have more determination than talent. I wanted desperately to live in the glamorous surroundings. I accepted as fictitious the tales of amateurs being discovered at lunch counters, yet I did believe it was important to be in the right place at the right time, and no place seemed so right to me in 1958 as Laurel Canyon.

When I answered a For Rent ad, the landlord told me the house had been taken that very morning. I asked Atara and Joe Morheim, a sympathetic white couple, to try to rent the house for me. They succeeded in doing so.

On moving day, the Morheims, Frederick Wilkie Wilkerson, my friend and voice coach, Guy, and I appeared on the steps of a modest, overpriced two-bedroom bungalow.

The landlord shook hands with Joe, welcomed him, then looked over Joe's shoulder and recognized me. Shock and revulsion made him recoil. He snatched his hand away from Joe. You bastard. I know what you're doing. I ought to sue you.

Joe, who always seemed casual to the point of being totally disinterested, surprised me with his emotional response. You fascist, you'd better not mention suing anybody. This lady here should sue you. If she wants to, I'll testify in court for her. Now, get the hell out of the way so we can move in.

The landlord brushed past us, throwing his anger into the perfumed air. I should have known. You dirty Jew. You bastard, you.

We laughed nervously and carried my furniture into the house.

Weeks later I had painted the small house a sparkling white, enrolled Guy into the local school, received only a few threatening telephone calls, and bought myself a handsome dated automobile. The car, a sea-green, ten-year-old Chrysler, had a parquet dashboard, and splintery wooden doors. It could not compete with the new chrome of my neighbors' Cadillacs and Buicks, but it had an elderly elegance, and driving in it with the top down, I felt more like an eccentric artist than a poor black woman who was living above her means, out of her element, and removed from her people.