J. D. Salingers

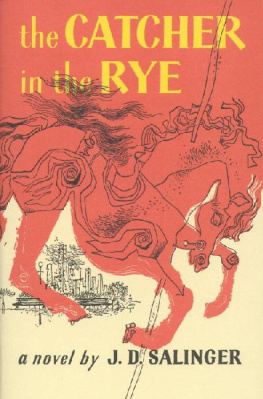

The Catcher in the Rye

J. D. Salingers

The Catcher in the Rye

A Cultural History

Josef Benson

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2018 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Benson, Josef, 1974 author.

Title: J. D. Salingers The catcher in the rye : a cultural history / Josef Benson.

Description: Lanham, Maryland : Rowman & Littlefield, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017035350 (print) | LCCN 2017036600 (ebook) | ISBN 9781442277953 (electronic) | ISBN 9781442277946 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Salinger, J. D. (Jerome David), 19192010. Catcher in the rye. | Caulfield, Holden (Fictitious character)

Classification: LCC PS3537.A426 (ebook) | LCC PS3537.A426 C3216 2018 (print) | DDC 813/.54dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017035350

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For my wife, Brenda,

whose central advice for this book was

Just tell a story. People love stories.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Stephen Ryan for offering the project to me. Thanks to my friend and editor Bob Batchelor for his editorial vision and grit. Thanks to my colleagues Tara Pedersen and Teresa Coronado for their input at the very beginning. Thanks to Jay McRoy for the many casual discussions and laughs that helped form the structure of the book.

Introduction

In 1991, when I was sixteen years old and living in Springfield, Missouri, my mother gave me The Catcher in the Rye for Easter, along with Thoreaus Walden. The books stuck out of a large Easter basket, jutting from green shredded plastic grass as though they had grown out of that synthetic ground like carrots. I was the same age as J. D. Salingers iconic protagonist Holden Caulfield, and my mom must have figured that Holden and Thoreau were better role models than Jim Morrison. I had recently quit playing football and baseball and discovered marijuana and the Doors. My hair was longer, and Id put on a little weight. The Catcher in the Rye revealed to me that contrary to what my English teachers had told me in grade school and high school, writing was not about following rules. Reading the novel for the first time demonstrated to me that writing could actually be truthful. Hanging out with Holden for those two hundred or so pages temporarily satisfied a hunger for a point of view that was not about following rules and sparked a lust in me to tell my own truth.

Throughout high school, Catcher became a touchstone for my friends and me as well as a sort of litmus test for other people. If people had read the book, then they were cool; if not then they likely werent. This counted for girls as well. I often introduced myself to new people as Holden, sometimes Holden Caulfield, just to see if they would recognize the name. Over the years I have come to realize that my experience was actually pretty common among first-time readers of the novel. I loaned my small white copy to each member of our circle of friends, and before long our gang developed a sort of literary reputation that was undeserved and stemmed mostly from our casual references to Holden, Salinger, Stradlater, and Ackley. I read several other books around that time, including The Great Gatsby, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Old Man and the Sea, and On the Road.

My first job during my sophomore year of high school was as an usher in a movie theater. I would stand behind a sort of podium with a slot in it for torn tickets and read. The ticket podium functioned nicely as a sort of lectern. As moviegoers approached me with their tickets, I would sometimes leave them standing there as I read to the end of a paragraph or otherwise found a convenient place to stop and mark my place.

Eighty-five years earlier, in Springfield, Missouri, a mob formed in the town square after two masked men attacked a man and a woman in a buggy. The man was beaten unconscious and the woman was raped. The man identified two particular black men as the perpetrators despite the fact that the attackers had worn masks and the woman stated positively that neither man had been her rapist. Soon both men were jailed anyway, and once word got out in town that two black men had raped a white woman, a lynch mob formed at the jailhouse. Both wrongly accused black men were hanged, and their bodies were burned in the town square. The mob returned to the jail later that night and hanged another black man who had been charged with an unrelated murder. This act of racial terrorism instigated a mass exodus of black people from Springfield, Missouri. Even today, one rarely sees a black person in Springfield.

One weekday afternoon in the summer of 1991, a white man approached me with his ticket and noticed that I was reading The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. That book should be banned, he said.

Really? Why do you say that?

Cause it has the word nigger.

I told the man that I thought it was probably a pretty accurate depiction of its usage during the time. The man snorted and asked me whether I was one of those college kids. I told him I was in high school. He then gave me his ticket. I tore it and gave it back to him, and as he walked by me he loudly farted.

I found this sort of reaction disgusting but also empowering and exciting. Finally, I had found something that struck fear in the hearts of people that was not inherently childish. I realized books were weapons that some folks found intimidating. I realized the knowledge one gleaned from books had power and that an intellectual youth was downright terrifying. More specifically, I had found something in the complexities of race that I felt was absolutely true and at the same time deliciously dangerous.

My dad is an educator and writer, and when I was in kindergarten in Des Moines, Iowa, before I moved to Springfield with my mother, stepfather, and sister, he enrolled me in a magnet school for diversity. There were only two or three other white kids in the whole class. The rest were black, Latino, and Vietnamese. I remember being particularly fond of the Vietnamese boys who barely spoke English and would get pulled out of class for extra language instruction. This early kindergarten experience certainly had a hand in my easy realization as a high school student that our culture was misguided in relation to how we think about race. Very early on I understood that the very concept of race was inaccurate, that the black and Vietnamese kids with whom I attended kindergarten were my classmates and friends, not members of other races.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.