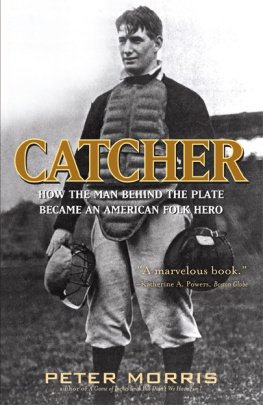

catcher

CATCHER

How the Man Behind the Plate

Became an American Folk Hero

PETER MORRIS

Ivan R. Dee

CHICAGO

CATCHER. Copyright 2009 by Peter Morris. First paperback edition 2010

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form. For information, address: Ivan R. Dee, Publisher, 1332 North Halsted Street, Chicago 60642 , a member of the Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group. Manufactured in the United States of America and printed on acid-free paper.

www.ivanrdee.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

The hardback edition of this book was previously cataloged by the Library of Congress as follows:

Morris, Peter, 1962

Catcher : how the man behind the plate became an American folk hero / Peter Morris.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

. Catchers (Baseball)United StatesHistory. I. Title.

GV.M 67 2009

796.357 ' 2309 dc 2008046501

ISBN : 978-1-56663-822-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN : 978-1-56663-870-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN : 978-1-61578-003-7 (electronic)

Acknowledgments

while writing this book , I have relied heavily on the generosity of many wonderful people. Tom Shieber of the National Baseball Hall of Fame has once again been extraordinarily helpful in directing me to photographs and in suggesting research sources and angles. I am also indebted to Tim Wiles and his staff in the Hall of Fames research department and to Pat Kelly of the Halls photograph archive for their invaluable help. I am deeply grateful to David MacGregor, Ron Haas, David Ball, Jan Finkel, Ben Dettmar, Paul Sorrentino, and Pete Schram for reading all or part of the manuscript as it evolved and for offering insightful comments. Reed Howard, Charles Weatherby, Bill Anderson, Richard Malatzky, Bill Carle, Bruce Allardice, Peter Mancuso, Bobby Plapinger, Cappy Gagnon, Darryl Brock, Dennis Pajot, Marty Payne, Jim Lannen, Frank Ceresi, John Thorn, and Tom and Delecia Carey have also made valuable contributions to my research or to my thinking on key topics. I also wish to thank the many dear friends and family members, too numerous to name, who have provided a listening ear, friendship, and support throughout this project. Finally, I have again been blessed to have the help of Ivan R. Dee and his staff in turning my vision of a book that captured the heroic age of catching into a reality. While all of these people have contributed to making this book better, the shortcomings that remain are my responsibility alone.

p. m.

Haslett, Michigan

January 2009

You have to have a catcher or youll have

a lot of passed balls.Casey Stengel

Introduction:

A Generation in Search of a Hero

soon after the birth of a boy named Stephen in Newark, New Jersey, in 1871 , ominous signs began to appear that he would struggle to find his place in the world. As the last of fourteen children of a devout fifty-two-year-old Methodist clergyman and his forty-four-year-old wife, Stephens early years were shaped by his parents puritanical views. Two years before his birth, his father had published a book entitled Popular Amusements , in which he took a dim view of dancing, tobacco, opium, alcohol, billiards, chess, and novel-reading. The book also predicted the demise of the then-new game of baseball, because everyone connected with it seems to be regarded with a degree of suspicion. Some who knew Stephen during his early years believed they had already detected signs of rebellion against his fathers views.

Then the sudden death of his father in 1880 turned the eight-year-old boys world upside down. Forced to leave the parsonage, his mother temporarily sent the lad to live with an older brother. Even after reuniting with him in a new home in Asbury Park, she immersed herself in temperance work, which often kept her away from home for lengthy periods. As a result, a neighbor recalled that when Stephen was scarcely out of knee pants he often arrived home from school or play, maybe skating on the lake, to find no supper. He would then range the neighborhood for food and companionship. The boy was finally sent off to school for good when he was thirteen. Thus during some of his most impressionable years he had been thrust out of a strict household and into a state of virtual orphanhood.

Stephen expressed his inner tumult by exploring many of the same worldly temptations that his father had condemned. Yet he did so in a strangely diffident way that suggested he felt haunted by the disapproval of his dead father and of his absent mother. Stephen cultivated a disaffected air and developed odd eating and sleeping habits that, along with his short stature and thin frame, made him appear disturbingly undernourished. Although cigarettes were still an uncommon vice, he habitually held a lit one in his fingersbut rarely was he seen to puff on it. It was as though he was deliberately striving to convince observers that he was unhealthy, when in fact he was blessed with both physical stamina and agility.

The young man attended four schools during the next five and a half years, and the frequent switches reinforced the persona he had already begun to develop. In the process, his sense of alienation hardened into a mask that hid his emotions. It was his pose, recollected one classmate, to take little interest in anything save poker and baseball, and even in speaking of these great matters there was in his manner a suggestion of noblesse oblige . Undoubtedly he felt himself peculiar, an oyster beneath whose lips there was already an irritating grain of some foreign substance. Outsiders saw in the youngster only a contradiction, self-depreciation coupled with arrogance, which has puzzled so many.

Since Stephen was gifted with a rich and inventive imagination, he might have been expected to channel his pent-up energies into one of the fine arts. Instead he concentrated them on baseball, one of the many activities that had troubled his father. More particularly, Stephen became obsessed with the position that had become central to the now professional sportthe catcher. In contrast to his usual hesitancy, he reportedly boasted that no pitcher could throw a ball he couldnt catch bare-handed. The specific source of this statement is dubious, but such displays of courage were so fundamental to the catchers of this era that it seems likely Stephen said something along those lines. There is even reason to suspect that he dreamed of a career as a professional baseball player.

His mother had different plans for her son. In 1885 , hoping that Stephen would find a religious calling, she enrolled him in the seminary where her late husband had once been principal. After two years she abandoned that hope and sent him to a military school, no doubt wishing either to make a soldier of her son or at least to instill some discipline in him. Once again reality would prove very different as schoolwork continued to have little interest to the youngster while baseball, more than ever, functioned as a substitute. He took great pride in being the catcher of the school baseball nine and continued to catch bare-handed, treating his increasingly sore hands with iodine and witch hazel. Eventually, however, he gave in and donned a buckskin glove.

He was off to Lafayette College in the fall of 1890 , where his most frequent companions were the schools motley crowd of baseball enthusiasts. He hoped to make the varsity team in the spring but was foiled by his chronic neglect of schoolwork, and he withdrew at the end of the semester. In January 1891 , Stephen enrolled at Syracuse University, where he was entitled to a scholarship as the grandnephew of one of the founders. He moved into the Delta Upsilon fraternity house, and his attitude remained as lackadaisical as ever.