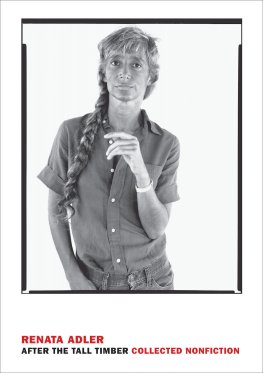

RENATA ADLER was born in Milan and raised in Connecticut. She received a B.A. from Bryn Mawr, an M.A. from Harvard, a D.dE.S. from the Sorbonne, a J.D. from Yale Law School, and an honorary LL.D. from Georgetown. Adler became a staff writer at The New Yorker in 1963 and, except for a year as the chief film critic of The New York Times, remained at The New Yorker for the next four decades. Her books include A Year in the Dark (1969); Toward a Radical Middle (1970); Reckless Disregard: Westmoreland v. CBS et al., Sharon v. Time (1986); Canaries in the Mineshaft (2001); Gone: The Last Days of The New Yorker (1999); Irreparable Harm: The U.S. Supreme Court and the Decision That Made George W. Bush President (2004); and the novels Speedboat (1976, Ernest Hemingway Award for Best First Novel) and Pitch Dark (1983).

MICHAEL WOLFF , currently a contributing editor at Vanity Fair and a columnist for The Guardian, USA Today, and British GQ, is one of the most prominent journalists and pundits in the nation. He has written numerous best-selling books, including The Man Who Owns the News: Inside the Secret World of Rupert Murdoch, Burn Rate, and Autumn of the Moguls. He appears often on the lecture circuit and is a frequent guest on network and cable news shows.

RENATA ADLER

AFTER THE TALL TIMBER

COLLECTED NONFICTION

PREFACE BY MICHAEL WOLFF

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Selection copyright 2015 by NYREV, Inc.

Copyright 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1976, 1979, 1980, 1987, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2015 by Renata Adler

Preface copyright 2015 by Michael Wolff

All rights reserved.

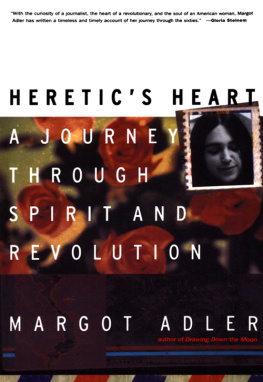

Cover photograph: Richard Avedon, Renata Adler, writer, St. Martin,French West Indies, March 8, 1978 The Richard Avedon Foundation

Jacket design: Katy Homans

Adler, Renata.

[Works. Selections]

After the Tall Timber: Collected nonfiction / by Renata Adler ; preface by Michael Wolff.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-59017-879-9 (hardback)

I. Title.

PS3551.D63A6 2015

818'.54dc23

2014038528

ISBN 978-1-59017-880-5

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

RENATA ADLER has become something of a cult figure for a new generation of literary-minded young women since the 2013 re-release of her novels, Speedboat (1976) and Pitch Dark (1983). Those books represent an early point, and in many ways a high point, in the portrayal of a modern sort of angstvulnerable women adrift in both the psychological and actual world. Adler herself can often seem like an iconic figure of fragility and lostness with her long bouts of literary absence and silence.

Here, however, in this collection of her most significant journalism, she is a diametrically opposite figure: a fierce and aggressive writer, known and feared and sometimes shunned for turning her stone-cold and contrarian judgments on her own professional class. I do not think it is an exaggeration to say that her writing is some of the most brutal ever directed at journalism itself.

Shortly before the publication of Gone, her broadside against The New Yorker and what the magazine became after it was sold in 1985 by its original owners, I was at a cocktail party on Manhattans West Side at the home of a New York Times cultural supremo attended by a set of publishing myrmidons of frightening standing and lockstep opinions. Following the whispered name Renata, I literally intruded on a clucking circle of these reproachful men planning their counterattacks against her: something must be done.

The writer Harold Brodkey, her friend and colleague at The New Yorker, once said to me, in the 1970s when she was having her famous and glamorous moment, that in his view, Renata could not decide whether to live an interior writers life or an exterior activists life. At the time, I thought his comment was about her work in Washington in 1974 with the House Judiciary Committees impeachment inquiry staff, where she had become a sort of historys ghostwriterrecruited to make inarticulate politicians sound like men worthy of impeaching a presidentand then her decision, at the peak of her fame, to enroll at Yale Law School. Should she seek real worldly power or continue as a mere writer on the sidelines? (It is quite extraordinary to consider that real power might have been within her grasp.)

In fact, I think I misunderstood what Brodkey was saying. What she was wrestling with was not career suitability, but her divided nature: on the one hand, muddled fear and vulnerability, and on the other, clearheaded outrage and scorn.

These feelings are not, of course, mutually exclusive.

A persons vulnerability and fears do not mean that he or she cannot also summon a particular courage. Perhaps such fear compels a person to redouble his or her efforts and boldness. Adler, who, among her friends, is well known for not being able to navigate a few blocks or keep her possessions about her, nevertheless, during a particular period of twentieth-century turmoil showed up for the civil rights movement in Selma, Alabama, the genocidal conflict between Nigeria and Biafra, and the American descent into Vietnam.

It is this contradictory nature, I believe, that has made her such a conundrum: she seems so appealing and uncertain (ever in need of protection) and then changes her clothes and goes to war. Not to mention the fact that she has often gone to war with her own colleagues, making her not just a confusing figure but an anathema as well.

At some point, perhaps quite unaware, she crossed over from a career as a cosseted insider to a what-ever-are-we-going-to-do-with-her outsider.

She was born in Milan in 1938 to parents fleeing Nazi Germany. She grew up in Connecticut and went to Bryn Mawr, then to graduate school at Harvard and the Sorbonne. In 1963 she joined The New Yorker as a staff writer.

For the next twenty years or so, she was a leading light in a particular brilliant period of American writing. She was an it girl, complete with the iconic look and memorable pictures by Richard Avedon, provocative and fashionable. (I recall my parents, culture vultures in suburban New Jersey, discussing her with great awe.) The New Yorker then was the equivalent of something similar to HBO nowyou wouldnt have missed it, or her.

In 1968, she became the New York Times film critic (the first woman in the job when being the first women was a miraculous transformation) at a moment when writing about film was, arguably, more influential than making filmsand when The New York Times was the first and last critical word. In the early 1970s, she went to Washington where she became the Watergate committees writerat the epicenter of the most momentous public event of the era. Then came Speedboat, followed by Yale Law School, then Pitch Dark; then came her book Reckless Disregard, about the big twin libel lawsuits of the early 1980s, Westmoreland suing CBS, Sharon suing Time; and then, practically speaking, nothing.

Writers careers, even ones that have reached a great height, are fragile things, and they can go wrong for many reasons and as the result of many choices: money, drugs, Hollywood, among others.