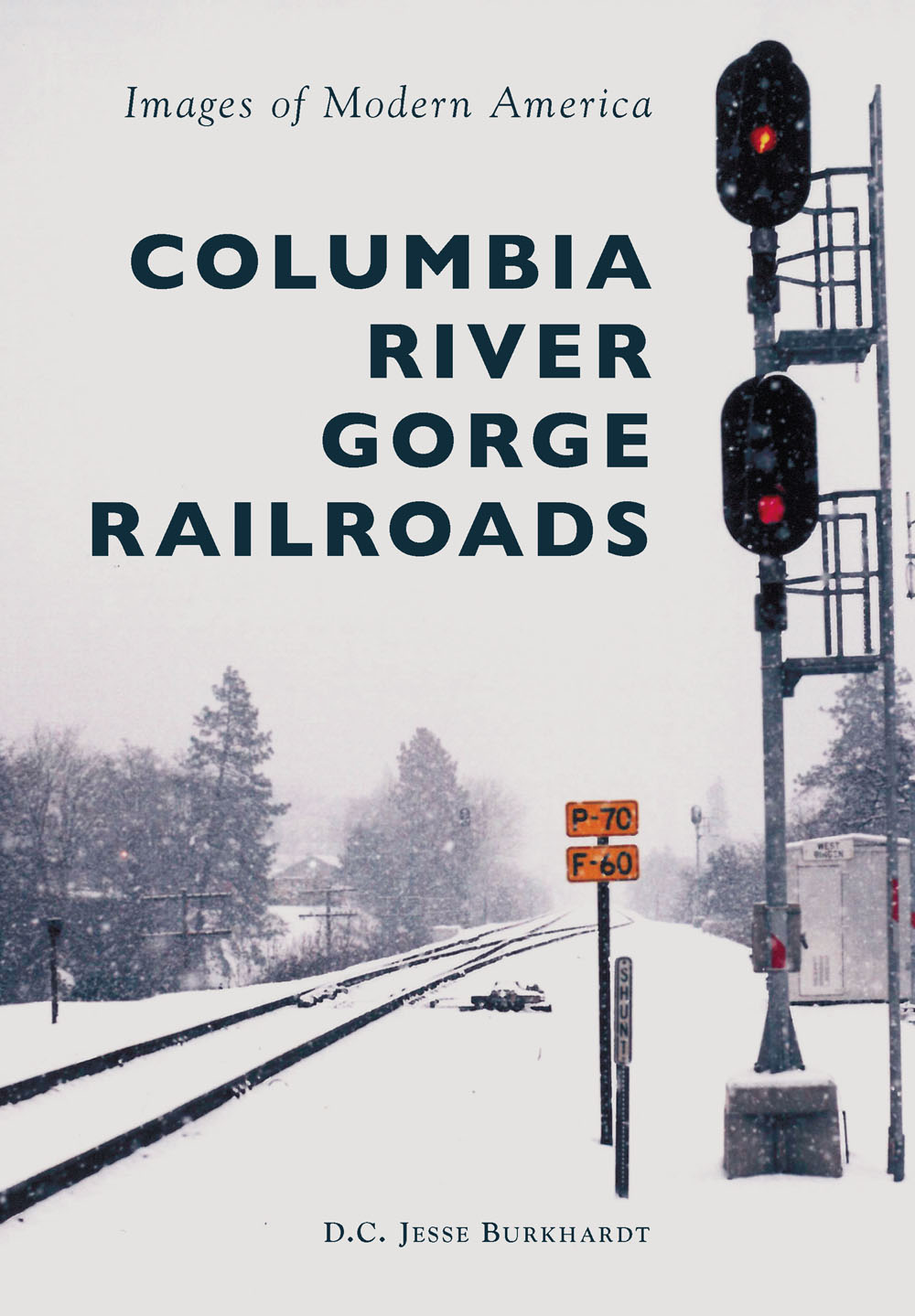

Images of Modern America

COLUMBIA

RIVER

GORGE

RAILROADS

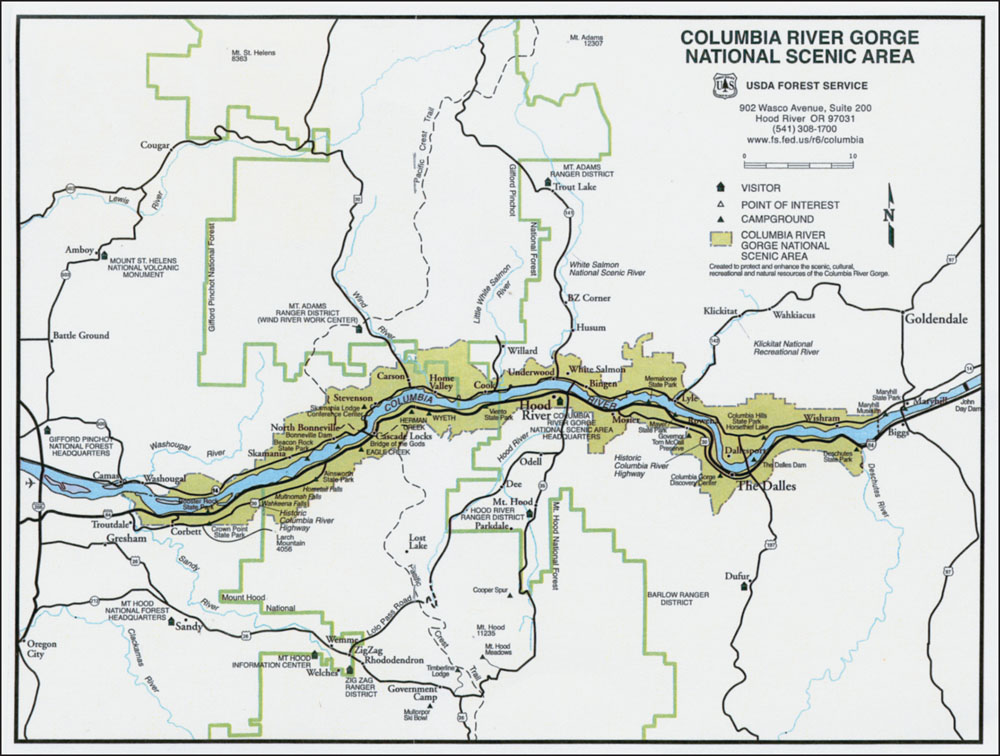

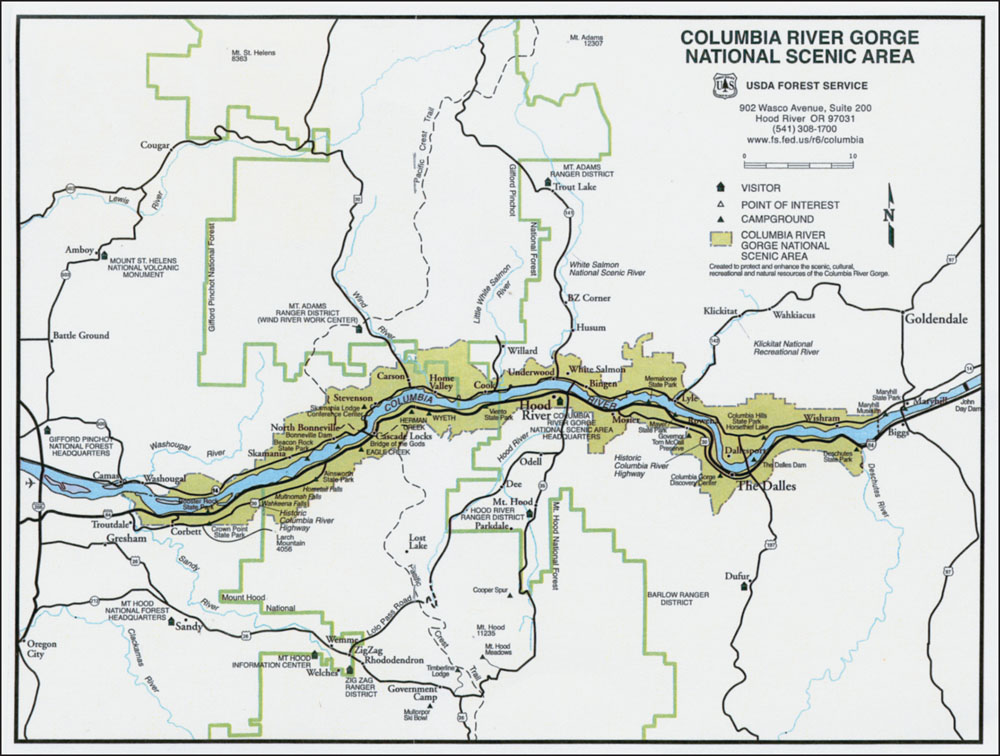

NATIONAL SCENIC AREA. The area shaded in dark green shows the boundaries of the 292,500-acre Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. The Columbia River separates the states of Oregon and Washington, with Washington north of the river and Oregon to the south. (Courtesy of the US Forest Service.)

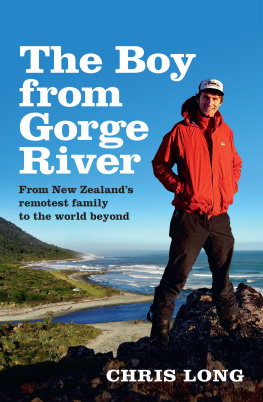

FRONT COVER: With snow flying on a January day in 2008, a BNSF signal tower at West Bingen, Washington, displays a cautionary amber over red. (Photograph by D.C. Jesse Burkhardt.)

UPPER BACK COVER: A Union Pacific freight rolls westbound through majestic Columbia River Gorge scenery near Rowena, Oregon. (Photograph by D.C. Jesse Burkhardt.)

LOWER BACK COVER (from left to right): A kiteboarder races with the wind on the Columbia River near Underwood, Washington, as a Union Pacific container train passes behind him; Mount Hood Railroad No. 18 steams away at the historic depot in Hood River, Oregon; an eastbound BNSF grain train rolls past a bright patch of desert parsley. (All photographs by D.C. Jesse Burkhardt.)

Images of Modern America

COLUMBIA

RIVER

GORGE

RAILROADS

D.C. JESSE BURKHARDT

Copyright 2016 by D.C. Jesse Burkhardt

ISBN 978-1-4671-3482-8

Ebook ISBN 9781439655047

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015942839

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To my Dad and Mom, Robert E. Burkhardt and Lois J. Burkhardtfor raising three wild boys so well and always being there for us.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to thank the following individuals who contributed to this book in various ways: Henry Clougherty and Sara Miller, editors at Arcadia Publishing, for being especially responsive and helpful and for trusting me to get it right; Kathy Fuller, Hillsboro, Oregon, for proofreading and insights; the staff of Pro Photo Supply, Portland, Oregon, for wonderful expertise and supplies; Elaine Bakke, publisher of the Enterprise, White Salmon, Washington; Marie Burkhardt, Aloha, Oregon; Clare Burkhardt, White Salmon, Washington; Oregon State Rep. Susan McLain, Forest Grove, Oregon; Diana Campos, US Forest Service, Hood River, Oregon; Darryl Lloyd, Long Shadow Photography, Hood River, Oregon; AshLee Wood and Kristen Ritter, Lantern Press, Seattle, Washington; Larry Moon Yaek, St. Clair, Michigan, for sharing the magic of Owosso on July 4, 1974; Greg Stadter, Phoenix, Arizona; Bob Dobyne, owner of Mirror Image Photos in Bingen and Dallesport, Washington; Chris Jaques, The Dalles, Oregon; Zach Tindall, Husum, Washington; Jim Tindall, Husum, Washington; Henry Balsiger, Snowden, Washington; Sophia Mathelier, Arcadia Publishing; Gus Melonas, BNSF Railway, Seattle, Washington; Michael Whiteman, Ashland, Oregon; Ben Seagraves, White Salmon, Washington; Olivia Passieux, Forest Grove, Oregon; Archer Mayo, White Salmon, Washington; Renae Cannon, Snowden, Washington; Tom Lacinski, Maple City, Michigan; Scott Sparling, Lake Oswego, Oregon; Leslie Jackson, White Salmon, Washington; Keith McCoy, Husum, Washington; all the railroad crews and support workers (including the crew-hauling drivers for PTI) who operate the rail network in the Columbia River Gorge; and my reliable and constant companion cameras over the years: first, a Pentax K-1000, and, later and currently, a Canon XSI.

INTRODUCTION

Railroads caught my spirit when I was a kid growing up near an east-west mainline in southern Michigan. The route that went past my boyhood home was a fast, modern Penn Central freight line that stretched from my hometown of Jackson, Michigan, to Elkhart, Indiana. There was something magical about standing alongside those tracks in Jackson, feeling the wind in my face and seeing the distant twinkle of an emerald signal light as the rails reached westbound toward an unknown horizon.

One summer, I experienced an unusual connection with the steel rails. On the afternoon of July 3, 1974, I was hiking in Owosso, Michigan, where an east-west mainline of the Grand Trunk Western (GTW) paralleled the tracks of the Ann Arbor Railroad. Only a short strip of tall weeds separated the two routes. With the July 4 holiday looming, the tracks of both carriers rested silent and still. As dusk approached, I cut through waist-high weeds, clambered up the GTWs roadbed, and looked to the west. There was a red signal shining in the distanceabout a mile off, I figured; maybe a bit farther. As I stood on those height-of-summer tracks and gazed westward, that light seemed to hold me with a mystical pull. For long minutes, I could not take my eyes away from that deep red glow shimmering in the waves of heat radiating from the roadbed gravel. The sight was haunting and beautiful.

A year later, I pointed my 1967 Dodge Dart westward, following the tracks until I arrived at and eventually settled in a region I have come to love as much as my home state: the Columbia River Gorge of Washington and Oregon.

There is an old saying: The only constant is change. In the Columbia River Gorge, change is truly eternal. The gorge was formed through a combination of volcanic activity and the Missoula Floods, a series of cataclysmic floods at the end of the last Ice Age, about 15,000 years ago. These floods periodically rushed down the course of what is now the Columbia River and scoured out the gorge region, fashioning stunning, deep canyons and rocky landscapes in the process.

As spectacular as the scenery often is in the gorge, with its tall waterfalls and steep cliffs, a dramatic political event also forever altered the regions environment. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Act, which mandated the protection and enhancement of scenic, cultural, natural, and recreational resources in the gorge, as well as providing support for the regions economy. The act protected roughly 292,500 acres in an 85-mile-long corridor on both sides of the Columbia River. The territory stretches roughly from Troutdale, Oregon, and Washougal, Washington (at the National Scenic Areas western end), to Wishram, Washington, and Celilo, Oregon (to the east). The designated area is a land of scenic wonder revered by tourists and photographers for its natural beauty and by recreationalists for its fishing, kayaking, windsurfing, hiking, biking, and rafting.

The gorge is also home to two vital east-west rail routes. The first segment of the mainline tracks along the Columbia River in Oregon was completed in 1884 by the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company, which later became part of Union Pacific Railroad. On the Washington side of the river, the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway opened its gorge mainline in 1908.

In the late 1950s, construction of dams on the Columbia River forced the relocation of long segments of the rail lines through the gorge, as the dams backed up the rolling river and flooded tracks that had been in use for decades. Also in the 1950s, the railroad industry itself underwent a major transition as the steam locomotive era came to an end. The end of steam operations brought a striking visual change as well, because colorful new diesel units replaced the venerable steamers, which were generally black. As a result, as the 1960s arrived, the trains gliding across the Columbia River Gorge countryside were literally imbued with a new coat of paint as motive power flooded through the area in a rainbow of colors.

Next page