An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

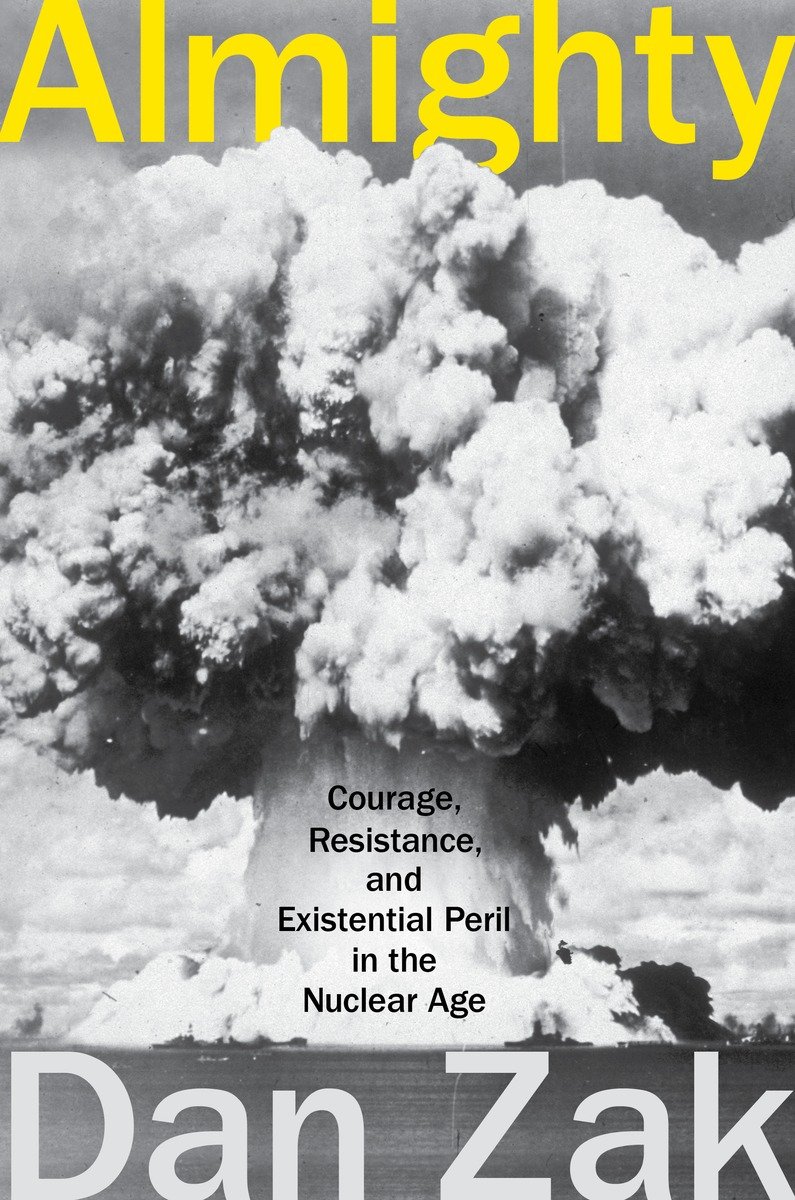

Copyright 2016 by Dan Zak

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Blue Rider Press is a registered trademark and its colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC

Blue Rider Press gratefully acknowledges permission to reprint Daniel Berrigans poem Hymn to the New Humanity 1984. Permission granted by John Dear, S. J., literary executor of the Berrigan estate.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zak, Dan.

Title: Almighty : courage, resistance, and existential peril in the nuclear age / Dan Zak.

Description : New York : Blue Rider Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers : LCCN 2016011566 (print) | LCCN 2016013992 (ebook) | ISBN 9780399173752 (print : alkaline paper) | ISBN 9780698189232 (ePub)

Subjects: LCSH: Antinuclear movementUnited StatesHistory21st century. | PacifistsTennesseeOak RidgeBiography. | Y-12 National Security Complex (U.S.) | CourageUnited States. | Government, Resistance toUnited States. | Nuclear weaponsMoral and ethical aspectsUnited States. | Nuclear weaponsSocial aspectsUnited States. | Nuclear weaponsUnited StatesHistory. | Nuclear weapons industryUnited StatesHistory. | United StatesMilitary policy. | BISAC: POLITICAL SCIENCE /International Relations / Arms Control. | HISTORY / Military / Biological & Chemical Warfare. | HISTORY / Military / Nuclear Warfare.

Classification: LCC JZ5584.U6 Z34 2016 (print) | LCC JZ5584.U6 (ebook) | DDC 327.1/7470973dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016011566

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Version_1

For my teachers

The seed of our destruction will blossom in the desert, the alexin of our cure grows by the mountain rock, and our lives are hunted by a Georgia slattern, because a London cutpurse went unhung. Each moment is the fruit of forty thousand years. The minute-winning days, like flies, buzz home to death, and every moment is a window on all time.

T HOMAS W OLFE , Look Homeward, Angel (1929)

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

T he zero hour approached but time seemed at a standstill. There was no cell service out there in the bramble, off a state highway named for a U.S. senator, past the point where brick estates gave way to matchstick shanties, past where foothills overtook steeples, where civilization faded down tangles of switchbacks. Off one sudden turn, a gravel drive hitched into the dim heather and got narrower, until it was just a mud lane rutted with tire tracks that wormed between warped barns. And there was the grove of sycamore, the rows of grapevine and corn, the handsome country house. A sanctuary. On the wraparound porch facing the vegetable garden, especially at night, it was possible to pretend that this was all there wasthat the world was made only of tranquil enclaves under ancient starlight.

They knew the world was not this way, so they retrieved three Red Cross blood bags from the refrigerator, snipped their corners, and began to funnel the blood into baby bottles on the porch.

The blood was human, and until very recently had been frozen for some time, so at first it appeared almost black and was cool to the touch. In the afternoon light, as it hit the thick midsummer oxygen of East Tennessee, the blood became cherry red. One man, who had done this type of thing several times before, funneled the blood over a ceramic bowl on a Ping-Pong table. He thought, God, let this all be to the good,in some way or another. The voice of a departed friend, who had first demonstrated this process for him 30 years earlier, was also in his ear: This is sacred stuff. This is the stuff of life.

The solemnity of the ritual kept it tidy. The funneling of the blood was one of many practical chores on the checklist, but it was also a private preparation for public prayer. To mark an object of scorn with blood was both symbolic and literal. It was a sacrament.

Nine people were at the house, including three who would put the six bottles of blood in their backpacks for illicit transport later that night. One was a Roman Catholic sister, 82 years old. One was a Vietnam veteran, age 63, who had no earthly possessions. One was a housepainter, 57, who knew that this could be his last day as a free man, or perhaps his last day alive. The remaining six at the house were the support team. The mission was initially scheduled for early Sunday, but on Thursday the group felt ready enough to go a day early. The sister in particular was anxious. Her life had been building to this moment.

Using box cutters, they scraped the peacenik bumper stickers from the drop-off car, which they would send to the junkyard afterward, just to be safe. A woman unrolled a long ribbon of red caution tape, wrote NUCLEAR CRIME ZONE in black marker after each DANGER , then rolled it back up. The sister, the vet, and the painter had the bolt cutters, the hammers, the flashlights, their typed statement of intent. They had observed one another over the week for hesitation, for spiritual disquiet. The man who funneled the blood remembered what his friend had told him years ago, before a similar mission: Dont macho bullshit your way through it. A young man in the support group had decided just that week not to go the distance. He was not as ready as the sister was, or as steadfast as her companions.

Now another woman was inside the safe house making two loaves of bread from scratch. One would be broken over dinner. The other would go into the backpacks with the bolt cutters and the blood. After the dough rose a second time, she used a kitchen knife to carve a cross atop both circular loaves. She herself was not a believernot in Jesus Christ, anyway, but certainly a believer in the spirit of the nights mission. If carving crosses into loaves of bread was in the service of peace, then doing so would be her pleasure.

The sister, the veteran, and the housepainter rehearsed likely scenarios out in the yard, which they imagined was the fenced perimeter of their target. Supporters played the role of armed guards who might discover them at any point in the mile-long hike over a wooded ridge. The possibilities ranged from the pedestrian to the fatal: What if one of them turns an ankle? What if the guards open fire, as they were authorized to do? What if they were thwarted before they got anywhere near their target? Would they be satisfied with their mission even if it was stopped early? What was their definition of victory?