Henderson - That Will Be England Gone: The Last Summer of Cricket

Here you can read online Henderson - That Will Be England Gone: The Last Summer of Cricket full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Little, Brown Book Group, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

That Will Be England Gone: The Last Summer of Cricket: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "That Will Be England Gone: The Last Summer of Cricket" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

That Will Be England Gone: The Last Summer of Cricket — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "That Will Be England Gone: The Last Summer of Cricket" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Published by Constable

ISBN: 978-1-47213-286-4

Copyright Michael Henderson, 2020

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Constable

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

For Giles Phillips

Cricket-lover, wine drinker, gentleman

Weve got to have some music on the new frontier

And in memory of Bob Willis, and all the blessed days we

shared with our friends

C rickets rope of destiny was woven by many hands, and not all the weavers wore cream flannels and striped caps. Those who shaped their innings with words also played a part.

There can be no summer in England without cricket, wrote Neville Cardus after watching one of his heroes, Frank Woolley of Kent, make a century at Dover. Allowing for romantic embellishment, which came so naturally to Cardus, all who love the game know what he meant. An English landscape without cricketers on the green between April and September is inconceivable.

Cardus created a mythology of cricket. He may not always have been realistic in his presentation of events, but he was truthful to the games spirit. Marcel Proust, who spent two decades of hard writing ordering a life of leisure, showed how much the imagination owes to memory. From that palate of mixed tones, the colourings of an unsuspected world, comes art.

I have never been a cricket fan. The word fan implies fanaticism, which is a step towards tribalism, of which the world has always had enough. I have been a cricket lover, however, since the day in September 1965 that I saw Fred Trueman bowling for Yorkshire against Derbyshire at Scarborough. His purposeful approach and high arm, an alliance of physical power and cunning, were my ludic equivalent of Prousts twin steeples at Martinville. Through half-closed eyes I can see him now, running in from the Trafalgar Road end. Those early memories ones first bag of chips, for example are the most vivid.

That love took another two years to ripen. When it did, in the pivotal summer of 1967, I was stubbornly unparochial. I wanted Lancashire to prosper. I hoped England would do well. Yet those attachments never occluded my love for the game, which meant more than winning and losing. The notion of postcode support never occurred. As Yeats wrote of the stage, and those who fill it with illusions more truthful than real life, the dream itself enchanted me.

John Arlotts commentary on Test Match Special opened a window to the wider world. Few voices in post-war Britain were so familiar, or so imitated. What made Arlott unique was that he never pressed his claims upon the listener, as do so many modern broadcasters, obsessed by the cult of personality. There was no striving for effect, no rhetoric for its own sake. He meant so much to the generation that had come through a war because he understood that cricket and sport in general mattered less than some zealots would have people believe.

Of all the pleasures lower than the arts, he told me one evening in November 1985, cricket is the highest. This, from a man who as a poetry producer at the BBC had known E. M. Forster, George Orwell and Louis MacNeice. His favourite companion in those convivial days was the maker of verses and taker of purses Dylan Thomas, the only man I ever kissed on the lips. He wrote a poem, Cricket at Swansea, as a tribute to the notorious sponger.

Arlott was pouring wines from Spain at the Vines, his house in Alderney, and talking about the players who had given him the greatest pleasure, from Jack Hobbs, The Master, to Ian Botham, whom he loved like a son. What relish for the game, and for life. If you gave him a pair of gloves, and put him in a ring, I reckon youd find out he was a pretty good boxer, too.

He understood that cricket yields its pleasures slowly. It is a game of languorous hours and sudden, occasionally violent shifts of fortune. More than any other sport it has an aesthetic sense. A days cricket, whether it is watched at Lords, Cheltenham or Ramsbottom, involves much more than the notching of runs. Every minute there are opportunities for digression and diversion.

A footballer plays his game for ninety minutes, said Arlott, and leaves an impression of skill, or finesse, or violence. A cricketer is showing you his character all the time. One may say as much of the cricket watcher. The game draws out something in the spectator that other sports, being shorter and more explosive, cannot.

Terence Rattigan thought it was beautifully inconclusive. In his screenplay for The Final Test , a peculiar film of 1954 which features members of the England XI in subsidiary parts uttering unlikely things, Rattigan has Robert Morley say that to go to cricket for excitement is like going to a Chekhov play for melodrama.

It is no coincidence that so many writers, interested in plot and character, have been drawn to cricket. Two, Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter, were Nobel Prize winners. Pinter used to send a draft of his plays to Beckett, who in his early days in Paris served as amanuensis to James Joyce, another cricket lover. As Pinter kept a copy of Ulysses by his bed it was almost an apostolic succession.

Pinters friend, Tom Stoppard, wrote a speech in The Real Thing that used the well-sprung cricket bat as a metaphor for the well-written sentence. What were trying to do is write cricket bats, says Henry, the playwright, to a sceptical lady who believes that political commitment trumps all. Occasionally members of the audience applauded the line. One evening, in the West End, a theatregoer booed: an act which suggested, more than the clapping, that Stoppard was right.

Uniquely, cricket is shaped by forces of nature. The season starts in spring, a time of renewal, and ends in September, with conkers on the ground and woodsmoke in the air. It charts an emotional course from hope to melancholy.

Although they play cricket in other lands, often more attractively than in England, cricket in our island is unique. The game is played on softer pitches, in milder weather, when the most common words are rain stopped play. A sudden shower, or the appearance of the sun, can have an important influence on the outcome of a match.

It is crickets emotional weather, as much as the climatic conditions, that sets it apart. A game that takes six hours to unfold each day, for five days at a stretch in Test cricket, offers plenty of scope for reflection. Conversations tend to meander, way leading on to way.

Those ruminative pleasures run counter to the spirit of our triumphantly demotic age. Sometimes it seems that unless everything is immediately understood by everybody there has been an assault on democracy. The popular, however vulgar or trivial, is venerated above the accumulated wisdom of the years.

Cricket has not been untouched. The sport that matured over a century of gradual change has altered almost out of recognition since the introduction in 2003 of 20-over cricket, a bowdlerisation aimed specifically at younger spectators. The atmosphere at grounds is coarser and occasionally, when strong drink has taken hold, unpleasant. The clubs are not concerned because it means people are spending money, and cricket is a poor game.

One consequence of this cultural shift has been the creation of strong loyalties that were not apparent before. Spectators beyond Lords have become more vocal, and less tolerant of good play by Englands opponents. The common law of applauding boundaries, or maiden overs, is observed less strictly. Matches have become contests of us against them.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

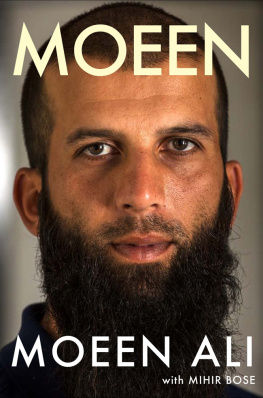

Similar books «That Will Be England Gone: The Last Summer of Cricket»

Look at similar books to That Will Be England Gone: The Last Summer of Cricket. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book That Will Be England Gone: The Last Summer of Cricket and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.