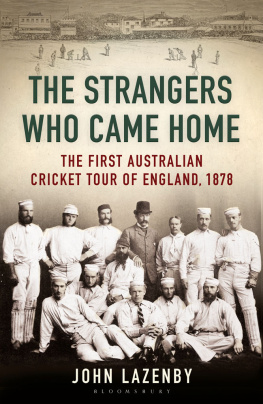

THE STRANGERS

WHO CAME HOME

To the memory of Richard, Virginia and Daphne

It might have been just another mail steamer leaving Sydney Harbour for San Francisco on Friday, 29 March, but for the presence of the 11 eager-eyed men who were grouped together on the hurricane deck. They were taking in the busy scene unfolding around them in the final moments before the sounding of the departure bell, when the air is clutched by a sudden sense of urgency and confusion, and the barked instructions of the crew mingle with the plaintive calls of goodbye from passengers and well-wishers alike.

For the 11 men it was to be their last sight of Sydney for eight months, perhaps longer. They had enjoyed a rousing farewell dinner with friends the night before at Punchs Hotel, behind Circular Quay on the corner of Pitt and King streets the scene of many a Sydney revelry and some of them were still feeling the effects. Their average age was no more than 23, and as they lifted their hats and smiled in quiet acknowledgment at the cheering crowd on the wharf, or talked and joked among themselves, it was obvious they were a tightly knit group and one that was already the focus of all attention. Uniformly trim, athletic looking and sun-bronzed, they were easily distinguishable from their fellow passengers many of whom had made it their business to find out who this band of brothers were. At first glance they might have passed for venturers on some perilous quest, pioneers, discoverers, gamblers, fortune-seekers perhaps, or sportsmen off to conquer distant fields: in fact they were all of these things, and more.

At 3.30pm, at least half an hour behind schedule, as the last flotilla of watermens boats crammed with well-wishers, friends and relations was still making its way back to shore, the RMS City of Sydney finally weighed anchor. To the sound of more cheers she glided out into the open expanse of water, where the steamships Bellbird, Britannia and Prince of Wales waited to escort her in a convoy of smoke and sirens to the harbour entrance. A sturdy iron-screw vessel of 3,017 tons and 360ft in length, with one funnel and two masts, elaborate rigging and just a hint of sail, the City of Sydney was comfortably capable of carrying over 500 passengers and numbered almost 70 crew. Safely stowed among her precious cargo of despatches and the orderly piles of trunks and sea chests, was a giant canvas bag, as heavy as it was unwieldy. It was the bane of all 11 men who took it in turns to heave it around with them wherever they went. The caravan, as it was aptly known, concealed the tools of their trade. It already looked as if it had been dragged to the ends of the earth and back, and splashed across it in whitewash were the unmistakable words, Australian Eleven.

As the small armada approached the mouth of the harbour, the band of the New South Wales Permanent Artillery, positioned beneath the yellow sandstone cliffs near South Head, struck up a stirring rendition of the American Civil War song Cheer, Boys, Cheer!. The heroic sentiment of it would not have been lost on the 11 men. The notes flew across the water towards them like the white wings of the yachts in the harbour. The men waved their hats in the air and called out in response, and as the City of Sydney steamed on alone between the Heads to the poignant strains of Auld Lang Syne and a fanfare of sirens, the soldiers returned three lusty cheers to send them on their great adventure. The water was beautifully smooth outside, a reporter for the Sydney Morning Herald filed, and the City of Sydney left here with every prospect before her of a speedy and pleasant voyage.

While the other passengers retreated to their cabins or the saloon, the men remained on deck feeling the steady pulse of the steamers mighty compound engines beating beneath their feet and watching the landmarks of Sydney shrink slowly into the distance. The sound of the band had soon faded away on the breeze, and their thoughts turned, inevitably, to the families and friends they were leaving behind and their long journey ahead. They expected to accomplish the voyage to San Francisco in a little under a month. There would be much playing of cards to while away the idle hours in between. The City of Sydney would call at Auckland en route, to pick up more passengers and mail, and then briefly in the tropics at Honolulu. After departing Auckland, however, they were venturing into the unknown. From San Francisco the 11 men would ride the Transcontinental Railroad across another vast and dangerous ocean the Great Plains travelling at a rate of almost 500 miles every day for a week until they reached New York. There, all being well, they were scheduled to board an Inman Line steamer, the City of Berlin, bound for the port of Liverpool, their final destination. These weary journeyers had only the haziest notion of what they might find once they reached England nearly seven weeks and more than 12,000 miles since clearing Sydney Heads. Except that they were finally coming home.

The pupils were quite as good as their masters

The story of the Australian Eleven began almost exactly a year earlier on a breezy sunlit afternoon in mid-March at the elm-fringed Melbourne Cricket Ground. The occasion was the Grand Combination Match, and was billed as the first representative game to be played on even terms between an English touring team (James Lillywhites All-England XI) and an Australian side (the Combined XI), a bold fusion of the most talented players from Sydney and Melbourne. Before then English XIs had routinely contested their matches in Australia against the odds, usually against teams of fifteen, eighteen or twenty-two men. The Grand Combination Match lasted four days, resulted in a 45-run victory for the inter-colonial XI and was designated, retrospectively, as the first Test to be played between England and Australia.

The term Test had yet to be coined, and no one could have foreseen the history that was in the making that Thursday afternoon: certainly not the Melbourne Argus, which described the unusually truncated four hours play as a spendthrift waste of an autumn day; nor the meagre 1,500 crowd there were almost as many non-paying spectators perched in the gum trees in Yarra Park who watched Sydneys Charles Bannerman cut the second ball of the match, bowled by Nottinghamshires Alfred Shaw, past point for an easy single.

Bannerman went on to score a glorious unbeaten 165, and the colonial press and public quickly dropped their indifference. Indeed, the Argus reported that no batsman in the world, not even W. G. Grace himself, could have played with more resolution and greater brilliance. Bannerman would more than merit his subsequent elevation as Test crickets first centurion. However, his influence in Melbourne was not confined purely to the field of play. It was in the full flush of victory that the idea for a tour of England by an Australian team was conceived, and, according to the Sydney fast bowler Fred Spofforth, it originated with the players: D. W. Gregory was the first to suggest such an experiment, in which he was supported by Charles Bannerman. The Englishmen, in the shape of the entrepreneurial James Lillywhite and Alfred Shaw, were not slow to offer their support. Our defeat on level terms in Melbourne was the last encouragement that our Australian friends needed to embark upon a first visit to England, Shaw recorded. Lillywhite and I had done our best to induce them to tackle the enterprise which we had confidence would be a success. That, though, is how it might have remained the glimmer of an idea had it not been for the actions of one man.