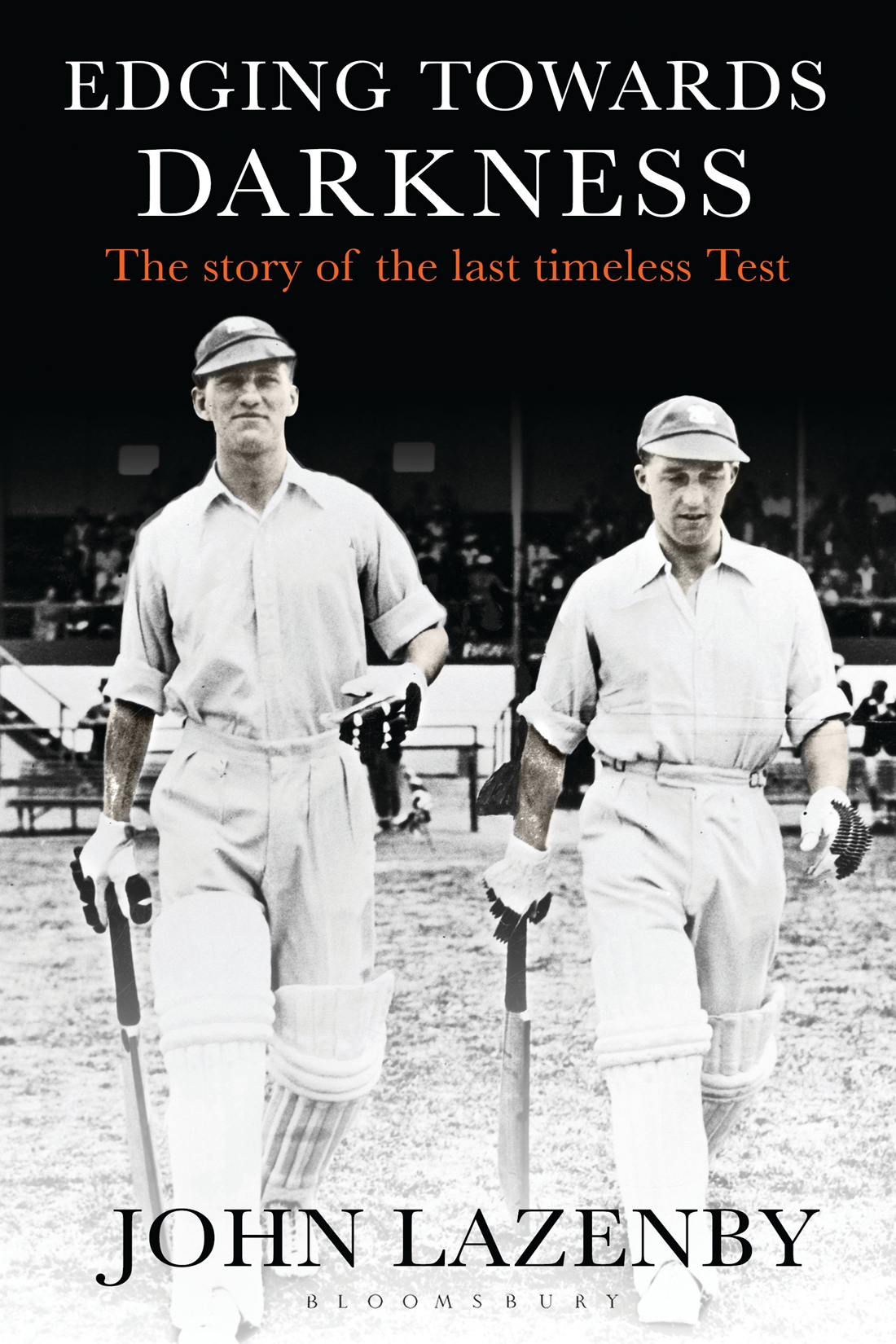

To the memory of the fallen cricketers of World War Two

Contents

Many thanks to Bloomsbury Publishing, especially to Charlotte Atyeo and Holly Jarrald for all their hard work and patience, and to Ian Preece for his excellent copy-editing. Thanks to my agent, Charlie Viney, for his continued support and belief in this project. I am indebted to Roger Mann for helping me with a book for the third time by supplying photographs and information from his wonderful collection; as always, his positive thoughts were much appreciated. Thanks to David Studham and Trevor Ruddell at the MCG library for all their assistance, and for successfully tracking down one particularly elusive book for me; and to Roger Page and Charles Davis, also in Australia, for their valuable contributions. I am most grateful to Neil Robinson at Lords for providing me with a fascinating glimpse into Bill Fergusons scorebook of the 193839 tour. A special thanks also to my New Zealand family, particularly Jean Meyer for being the best host and office manager that a writer could wish for. Finally, all my thanks to Sharon, for everything. As ever, I could not have done it without you.

A timeless Test match is played under no limitation of time and is designed to guarantee a decisive result. It is played until one side wins, however long that may take: hours, days... weeks. In theory, therefore, the timeless format eliminates all possibilities of a draw the bane of international cricket played on the benign and often contrived wickets of the 1930s. As it has the luxury of time at its disposal, a limitless match is also meant to ensure that any interruptions for bad weather will not prevent a game from reaching its ultimate destination: a positive outcome. Unfortunately, timeless cricket was sometimes prone to failing its own test...

Norman Gordon, the last surviving man to play in a Test match before the onset of the Second World War, died peacefully in his flat in the Hillbrow district of Johannesburg on Tuesday, 2 September 2014, aged 103. Gordon was also the first international cricketer to reach a century in years and a last cherished link to the age of steamship timetables, eight-ball overs and tall scoring, in the language of the day; when batsmen gorged themselves on perfect wickets and bowlers, more often than not, fed off the scraps.

Once a thriving suburb of colonial villas, bookshops and cosmopolitan values, Hillbrow is now regarded as one of the most notorious neighbourhoods in the city: a hotbed of crime, poverty and squats; a world many times removed from that of the genial former Test cricketer, who was still practising as an accountant deep into his 93rd year. In the words of one writer, it is a place much closer to hell than the heaven it used to be. But Gordon could not have moved away even if he had wanted to. The small flat he bought in the once fashionable Hillbrow, some 60 years earlier, would have cost more to sell than it was worth.

His good friend Ali Bacher, the former South African Test captain and cricket administrator who interviewed him for the television channel SuperSport shortly before his death, remembered an imperturbable character of strong personality, modest, engaging and always ready with a smile or a wry quip. Gordon refused to become a prisoner to his environment and told Bacher that all the time he lived in Hillbrow he never felt intimidated. There was only one occasion when he was bothered by someone at night, Bacher informed Cricinfo , but in general everybody knew him there. He lived life to the full and was much loved.

There was not much that could alarm a man who had seen and heard it all from the cataclysm of world war, the rise of apartheid, his countrys sporting excommunication, rehabilitation and subsequent regeneration, to the seismic shifts within the game he loved. He abhorred sledging, however I never heard a dirty word uttered in my entire career and reminisced unashamedly about a time when kinship between opponents was an essential tenet of the sport. Longevity was a recurring theme throughout his life. An avid golfer, he accomplished a hole-in-one at the age of 87 and played regularly until he was 96. As he explained once to SA Cricket magazine, with his customary gusto, he had no intention of spending his last days sitting in Hillbrow watching TV.

Gordon succeeded the New Zealander Eric Tindill as Test crickets eldest son after the hardy wicketkeeper-batsman passed away, aged 99, on 1 August 2010. A gifted all-rounder, Tindill also played rugby union for his country, winning a solitary cap at Twickenham on Saturday, 4 January 1936 in a match revered for two imperishable tries by the Oxford University undergraduate and Russian migr , Prince Obolensky, and for Englands first victory over the All Blacks. Years later Tindill confessed to smuggling the match ball off the pitch, tucked under his jersey on the final whistle, and returning to New Zealand with his prized trophy.

The young Gordon performed his own conjuring tricks with a ball. A right-arm fast-medium bowler who seldom tired, he was known as Mobil for the handfuls of Vaseline he rubbed into his dark unruly hair, though on the pitch he was the antithesis of a showman. He possessed an equable temperament, along with a priceless ability to swing the ball both ways at a lively pace, and was rated by none other than Walter Hammond as a bowler to bear comparison with the legendary Sussex and England seamer, Maurice Tate. Gordon preferred instead to compare himself to his countryman Shaun Pollock, whom he said he matched for pace and the similarity of their actions. In short, Norman Gordon of Transvaal was a captains dream.

Yet, for all his undoubted qualities, he played only five Test matches for South Africa, all against Walter Hammonds MCC tourists of 193839, in a series pitched against the backdrop of impending war. The last of these, at Kingsmead in Durban, was timeless and is now universally acknowledged as the timeless Test. Weighing in at a prodigious ten days the match stretched from 314 March 1939 and allowed for two rest days, while one days play (the eighth) was lost entirely to rain it is quite simply the longest Test ever played. A litany of records also perished in its wake and whole pages of Wisden were ruthlessly made obsolete. If that was not enough one player, the fastidious South African batsman Ken Viljoen, felt the need to have his hair cut twice during the game. Extraordinarily, the contest had not been expected to last beyond five days a distance that in all probability it might not have achieved, but for an unforeseen quirk of fate. Only the timeless games between Australia and England at Melbourne in 1929 (eight playing days), and West Indies and England in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1930 (seven days), come remotely close in terms of their durability, though the latter also ended farcically.

Timeless Tests are as old as the dawn of international cricket itself. Melbournes Grand Combination Match, as it was billed in 1877, and later designated as the first Test match to be played between England and Australia, was limitless but consisted of only four-ball overs and concluded shortly before lunch on the fourth day. In fact, all Test matches played in Australia before the Second World War were timeless, and the format was an integral part of the countrys cricketing culture for more than 60 years, before its inevitable extinction. In England, South Africa and the West Indies, timeless Tests were played only sporadically, where the concept was seen as nothing more than a last resort: a means of engineering a positive result if a rubber was all square or a side was one-up going into a final Test. England were leading South Africa 10 before the fifth Test at Kingsmead in 1939 and, as the series still remained alive, both sides agreed, under the conditions of the day, to play to a finish.