Contents

A VIEW FROM THE COMMENTARY BOX

Past and present

Introduction

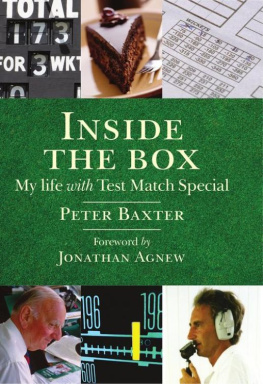

This book is a celebration of the golden jubilee of a radio programme.

Cricket commentary has been going much longer than 50 years, but what happened in 1957 created something of an institution around the name of that programme Test Match Special.

In the following pages is the story of how it came about. A live programme can only be as good as the people who take part in it and we have reflected on a half-century of such characters. The list of voices has been necessarily restricted to those who have taken part within England. It would have doubled in length had we included all those who joined in on overseas tours. That self-imposed rule has deprived us of Michael Carey, Ralph Dellor and even David Gower (who earned a Test Match Special commentators tie on a tour of the West Indies and was then promptly called into the England touring squad) and several others. I have also left out those who have only commentated on one-day matches and never done a Test Match. That list would have included no less a presence than Sir Tim Rice, who joined us during the World Cup of 1987 in India and Pakistan. His second match in Pune was between England and Sri Lanka, with whose players we were less familiar then than we are these days. Faced with an array of tongue-twisters, he opted for safety and listeners might have been surprised how often Vinothen John fielded the ball. The burly John popped up at long-on and deep third man, sometimes in the same over. A future version of this book might yet include Tim, as, with typical enthusiasm, he always greets me with, Still available!

We have told the story of how the programme whose threatened demise once prompted questions in the House of Commons came into being. At one stage in its history, indeed, such a sword of Damocles seemed regularly to hang over us as changes to radio networks gave planners nightmares which always appeared to bring them up against the great stumbling block that was TMS. Also included are the memories of many of the current habitus of the commentary box, from home and abroad.

Our listeners and our guests, from the highest to the lowest in the land, also have their place. Could any other game than cricket have thrown up such a programme? It seems very unlikely. Its pace, its structure, its history, its drama and its aesthetic qualities are the essential ingredients in the making of Test Match Special.

A former network controller once called TMS an art form. John Arlott called it Folk. Brian Johnston, in his own inimitable way, used to say, Were just a bunch of friends going to a cricket match and talking about it. Thatll do for me.

Peter Baxter

Soulbury, January 2007

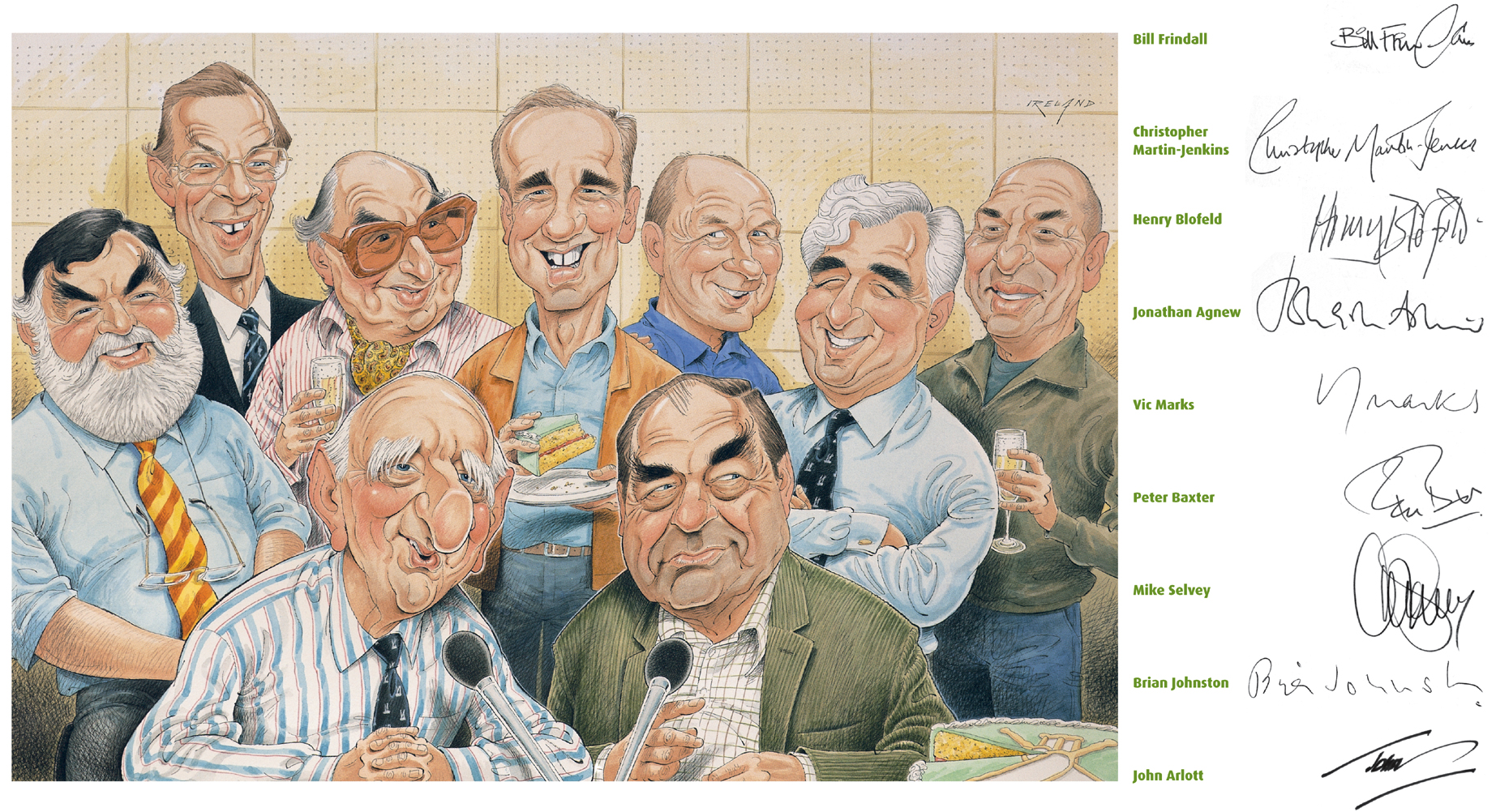

A live programme is only as good as the people who take part in it the TMS team on the day of Aggers debut, Headingley, 1991: (left to right) Bill Frindall, Christopher Martin-Jenkins, Don Mosey, Fred Trueman, Tony Cozier, Brian Johnston, Trevor Bailey, Jonathan Agnew, Vic Marks, Peter Baxter and Mike Selvey.

THE BIRTH OF CRICKET COMMENTARY

There is no evidence to suggest that the Reverend Frank Gillingham was aware of his place in broadcasting history when in May 1927 he became the first cricket commentator. Although in fact commentator is not really the word, because it was believed that ball-by-ball description of cricket was simply not possible.

Five years earlier in Australia, cricket commentary had been done for a state game and tried for Test cricket a couple of years after that. But the BBC in London had largely ignored those early steps in the far-off colonies. However, Radio Times made much of the groundbreaking significance of the Corporations coverage of Essexs match against the New Zealand touring team at Leyton in May, because they published a full-page article under the heading, Cricket on the Hearth, in which, after stating that description of every ball was clearly not possible, they explained, What will be done is this. A microphone will be installed in the pavilion at Leyton and the BBCs narrator will watch the whole of Saturdays play from there. At fixed times [between dance band music] he will broadcast an account of the state of the game.

So, in between waltzes and foxtrots, Gillingham, a former Essex player himself and a stirring preacher, delivered his eyewitness accounts of the game. These were not the 30-second reports which we are used to today, but five minutes or so on each occasion, so it is probable that he did get close to describing some live action as it happened.

Live sports commentary on the radio had started earlier that year, when Captain Teddy Wakelam had covered the England v Wales rugby international at Twickenham. Soon there was soccer from Highbury and the Oxford v Cambridge Boat Race, which was a tremendous technical undertaking. Several county matches, covered in the same style, followed that summer. Pelham Warner made the first broadcast from Lords in June and later, it is recorded, Gillingham seriously blotted his copybook by filling a rain break at the Oval by reading out the advertising hoardings. The great C.B. Fry also added radio reporting to his already remarkable CV that year.

But live sports broadcasts were not to everyones taste. Teddy Wakelam, who was regarded as the principal commentator on any sport, reported, after a difficult day at the Oval, that ball-by-ball commentary on cricket was not possible. And there was a further setback when Lance Sievking, the Head of Outside Broadcasts, who had conceived the idea of live sports coverage, was moved to Drama. It seemed that the right man to blow the spark into a flame was yet to arrive at the BBC.

In the second week of May 1927 Radio Times announced the BBCs groundbreaking coverage of the New Zealand tourists match against Essex at Leyton.

Happily in the early 1930s a great partnership was to launch real cricket commentary. Seymour de Lotbinire, first as producer and then as an imaginative Head of Outside Broadcasts in the footsteps of Sievking, perceived that with the right broadcaster ball-by-ball commentary of cricket could indeed be done. The rhythm of the game, he recognised, far from being impossible for radio, made it ideal. There was the build-up to a moment of violent action as the ball was bowled and then the time for reflection before the next release of action and that predictable pattern set a perfect template. De Lotbinire (Lobby to all who worked with him) had the genius to recognise the man and the sport as the perfect combination for radio description. Paint a picture and keep it the right way up, was the instruction.

The means to convey the game to a radio audience came to de Lotbinire in the person of Howard Marshall. Gillingham, Warner and Wakelam may have gone before, but Marshall was the true father of ball-by-ball cricket commentary in a manner that would not be out of place today. He had joined the BBC in his late twenties, with a rugby blue from Oxford and training in journalism behind him.