ON GRACE

AN ANTHOLOGY

EDITED BY

Jonathan Rice

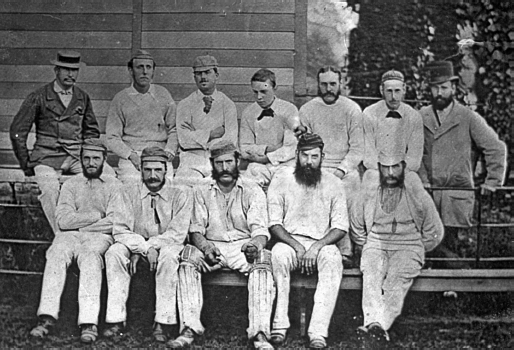

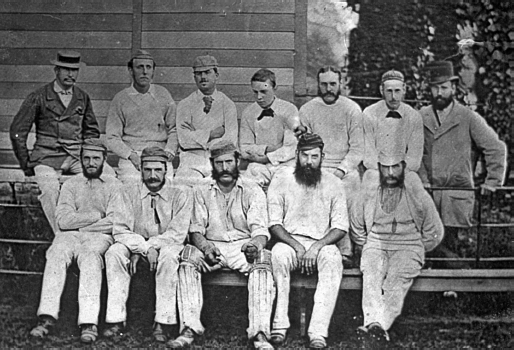

A Gloucestershire team photograph from 1877. WG is unmistakeable in the front row, with his elder brother EM on his left. Fred Grace is directly behind WG, while their cousin WR Gilbert is in the back row, third from the left. Courtesy of The Roger Mann Collection

Contents

Wisden was first published in 1864, the year in which William Gilbert Grace made his first impact in English cricket, by scoring 170 for South Wales against the Gentlemen of Sussex at Brighton at the age of not quite 16. This innings was big enough to attract the attention of the cricket hierarchy, even if the match was never considered to be truly first-class (a distinction that did not exist in 1864). His elder brother, Edward Mills Grace, then aged 23, was already established as the biggest run-getter in the world according to Sydney Pardon, and had spent the winter of 1863-64 with George Parrs team touring Australia. In 1864 cricket was divided into two separate but not mutually exclusive camps the amateurs, as exemplified by the Marylebone Cricket Club (the Earl of Dudley was president of the club in that year), and the professionals, who were grouped in the more northern parts of England, in the teams led by William Clarke and others, who toured the country playing cricket as All-England, The United Eleven and other such catch-all names.

Amateur cricket was, in the 1860s, somewhat in the doldrums. Matches were not played at Lords during the grouse season, and the quality of the matches played there during the rest of the year was not always high. A new secretary, R. A. Fitzgerald, had been appointed in 1863, and it was his responsibility to restore the clubs image, its finances and its position as the arbiter of all matters cricketing. He was starting from a fairly low base. Professional cricketers were not, of course, allowed to be members of the Marylebone Club, but they were employed to bowl in the nets at the members, and they were allowed to play for MCC and Ground against all-comers.

John Wisden was a professional cricketer. He finished playing in 1863, but by this time he was already building his sports-equipment business, and it seems that he thought a slim publication looking forward to the cricket season each year would act as a useful advertisement for his company. There were already other publications on cricket Frederick Lillywhites Guide To Cricketers, for example, had been published regularly since 1849 so John Wisden was not being original in his venture, but he did manage, perhaps more by luck than good judgment, to hit a nerve with the public, who took to his little book from the outset. His timing turned out to be perfect.

Wisden did not edit the book himself. It was printed by W. H. Crockford in Blackheath, who is also described as compiler, but the main editor from the outset seems to have been W. H. Knight, a journalist with The Times, who continued to edit the Almanack until his death in 1879. The contrast between Wisden, the professional cricketer, and Knight, the Times journalist, gave their publication an editorial tension that worked. Wisden lived in the world of the professionals, his former colleagues, while Knight and even more so future editors like Charles and Sydney Pardon was more closely involved with the upper strata of Victorian society on display at Lords, the universities and the public schools. In their Almanack, they chronicled all cricket, taking in both amateur and professional, and those who trod the narrow line between the two.

Cricket was changing in mid-Victorian times. Roundarm bowling had been legalised earlier, but in 1864 overarm bowling was officially sanctioned, and by mastering this action bowlers became quicker, more accurate and more devious in their spin. Overs were of only four balls then: it was not until 1889 that they were increased to five balls, an experiment that lasted only a decade. In 1900, they were increased again, this time to the present six balls.

In 1864 there were also no declarations allowed: with the quality of the pitches as poor as they were, few innings lasted long enough for a captain to want to declare them closed. But at about this time, mechanical lawnmowers were coming into common use, which meant that the quality of pitches improved greatly. This led occasionally to farcical periods of cricket when the batsmen were trying to get out and the fielders were trying to keep them in. In 1889, declarations were permitted for the first time, but only on the third day of a match. In 1900, this law was relaxed so that declarations were allowed any time after lunch on the second day. Even though Wisden probably did not realise it at the time, cricket was metamorphosing into a sport that could and would capture the public imagination. All it needed was a hero.

That hero was, of course, William Gilbert Grace. The man who became known to the world soon enough by his initials only, but still to some of his intimates as Gilbert, was born into a comfortably middle-class family living in the Gloucestershire countryside. His father was a doctor, and in due course he and his elder brother Edward also became doctors, as would have his younger brother Fred had death not taken him before his 30th birthday. The Graces ranked solidly in the middle of Victorian society, halfway up, neither up nor down.

WG was exactly what cricket needed, and therefore he was exactly what the fledgling Wisdens Almanack needed. He was the perfect hero not only for cricket enthusiasts, but also for all Victorians. The Victorian educated middle classes had a certainty about them an absolute conviction that their way of life was the best of all possible worlds and that the benighted heathen needed to be told that fact often and loudly. Muscular Christianity, as it was known the personification of spiritual values through physical activity was a crucial part of the message of the British Empire, and cricket was perhaps the most important component. Cricket, in the Victorian mind, taught all the values of honesty, integrity and team spirit, as well as the well-thumbed values of play up, and play the game (which is a quotation from a poem written in 1892, more than a quarter of a century into WGs career). Cricket is still today the sport most associated with the British Empire.

There is no evidence to suggest that W. G. Grace was any more a keen Empire-builder than the next man, but his dominance of cricket for almost 40 years made him a symbol of British sporting greatness, and a character about whom the British public could never tire of reading. Wisdens Almanack was fortunate to have WG to write about as it grew in authority.

There is, however, a strange equivocation in Wisdens attitude to WG. While his brothers received almost uniformly good reports from Wisdens reporters, their attitude to the Champion, as they quickly began to name him, was grudging in its praise. In the first few years of Wisden, and of WGs career, there were no reports, only scorecards, so there was no opportunity for the editors to comment on the style or quantity of the runs scored. But once the editors took the decision to comment on the matches played (a decision almost certainly influenced by the colossal scores WG was racking up each season) it is noticeable that while lesser batsmen may be praised for their faultless play or fine strokes in making, say, 40, the comments on WGs century in the same innings might be not much more than that he was dropped when he had only scored four.

Next page