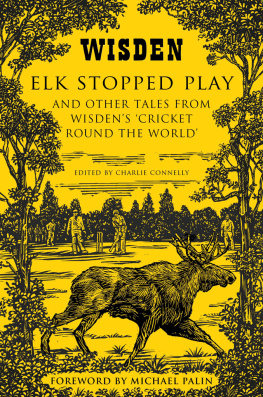

First published in Great Britain 2014

Original material

Copyright Charlie Connelly 2014

Material reproduced from

Wisden Cricketers Almanack

John Wisden & Co

Foreword copyright 2014 Michael Palin

Illustrated letters copyright David Bromley 2014

This electronic edition published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

The moral right of the author has been asserted

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

John Wisden and Co

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc

50 Bedford Square

London

WC1B 3DP

www.wisden.com

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

All rights reserved.

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 4088 3237 0

eISBN 978 1 4088 3238 7

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters here.

To my dad, George Connelly, for teaching me from an early age the soul-enriching benefits of both cricket and travel.

The game is essentially English, and though our countrymen carry it abroad wherever they go, it is difficult to inoculate or knock it into the foreigner. The Italians are too fat for cricket, the French too thin, the Dutch too dumpy, the Belgians too bilious, the Flemish too flatulent, the East Indians too peppery, the Laplanders too bow-legged, the Swiss too sentimental, the Greeks too lazy, the Egyptians too long in the neck, and the Germans too short in the wind.

Charles Box, The Theory and Practice of Cricket, 1868

We tend to think of cricket as the quintessential English game, associated with tall trees, church towers, snug pubs and overgrown outfields, but in my travels Ive seen it played in very different surroundings. Halfway up a mountain in Pakistan, where a lofted six could send the ball ten thousand feet into the Indus valley and where a boundary catch could be fatal; on the deck of a container ship; in car parks; on railway lines; and once, on my Full Circle journey, on a brownfield site in Hanoi belonging to the Vietnamese Air Force. This had many problems, one being the non-appearance of the captain who was bringing the pitch. When eventually he arrived, carrying twenty-two yards of coconut matting over his shoulder, a head bearing the cap and red star of the Peoples Army popped up from behind a wall, and watched with increasing bewilderment as the two teams, India and the Rest of the World, limbered up. When the first boundary was struck hard towards the wall, the head disappeared smartly. Midway through the third over, a phone rang in the captains pocket as he crouched at third slip. Did we know that this was a sensitive military area? The captain vainly tried to explain that it was just a game, when an entire detachment of soldiers, the majority of them women, marched out to bring the game to a premature close of play.

Anything that the military see as a threat has to have something going for it, and if I were a paranoid general I would be extremely concerned about the revelations in Charlie Connellys book. Its clear that cricket, with all its attendant subversive potential, is creeping across the world. From Antarctica to Ethiopia, from North Korea to St Helena, there are fielders fanning out and guards being taken. Balls have been struck across national boundaries and doubtless from one hemisphere to another. I know this and Charlie Connelly knows this because the indispensable oracle that is Wisden Cricketers Almanack has been charting every detail of crickets global advance. This is how we know that a hundred years ago there was a King of Tonga who inflicted so much cricket on his subjects that they had to limit the days it was played, to avert famine. Thanks to Wisden and Connelly I now know that Don Bradmans grandmother was Italian, that there is an Estonian Cricket Board, and that one of the greatest of all team names, the Gondwanaland Occasionals, harks back to a time before the continents assumed their present shape, when cricket was played by the very earliest life forms. This book is brimful of the sort of esoteric facts that cricket followers love, but its also a terrific travel book, to be read not just with a Wisden by your side, but an atlas too. And, of course, a large gin and tonic. Or a caipirinha, a sliwowitz or a stiff pisco sour.

Elk Stopped Play is a universal pleasure and a hugely enjoyable reminder of a game which combines unquenchable enthusiasm with incomparable eccentricity. And its good to know that there is barely a corner of Gods earth where you can walk without at least some chance of being hit by a cricket ball.

Michael Palin

London, July 2013

When I was a boy my sister and I were sent over to The Hague one summer to stay with some Dutch friends of our parents. I wasnt happy. At Headingley New Zealand were on their way to their first-ever Test victory in England, and Id become a little bit obsessed with Lance Cairns; he of the shoulderless club of a bat with which hed smite enormous sixes to all corners, before lumbering up to the wicket with the grace and elegance of a prop forward learning to unicycle, and bowl out teams with his chest-on, banana-shaped outswingers.

But just as Cairns was celebrating taking seven English wickets on the first day as part of a performance that would earn him the Man of the Match award, I was being plucked from the sofa and the company of Jim Laker and Peter West and deposited on an aeroplane to Holland where, as far as I knew, theyd never even heard of cricket.

Fascinating city though The Hague undoubtedly is, in hindsight I cant help thinking my hosts must have noticed how underwhelmed I was by the Gemeentemuseum and the Madurodam miniature park. The medieval town centre would ordinarily have coaxed forth wide-eyed wonder, or at least polite oohs and ahhs, but instead I was scanning the shop fronts in vain for signs of an English newspaper that might bring news from Headingley. It was summer, there was a Test match on, my new favourite player was taking it by storm, and here I was in a barren cricketing wasteland that might as well have been on the other side of the Horsehead Nebula as the North Sea. Id never been wrenched from cricket like this before and at just 12 years old I was already finding life outside its comforting linseed-infused cocoon to be riddled with crushing ennui.

One afternoon, we were in the back of the car on our way somewhere and I was wondering wistfully what damage Lances batting might have caused windows within a half-mile radius of the Kirkstall Lane end when, between some trees, I saw what I assumed at first to be a mirage induced by my cricket cold turkey. The car slowed in traffic as we got closer, and my mouth fell open as I realised what I was seeing.

Next page