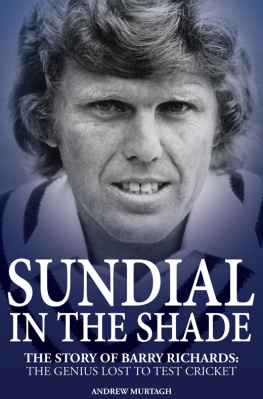

To Lin Murtagh, my wife.

Without whom I would probably not

be here today.

First published by Pitch Publishing, 2015

Pitch Publishing

A2 Yeoman Gate

Yeoman Way

Durrington

BN13 3QZ

www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

Andrew Murtagh, 2015

All rights reserved under Internationaland Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been grantedthe non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No partof this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or storedin or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express writtenpermission of the Publisher.

A CIP catalogue record is available for this book from the British Library

Print ISBN 978 178531-010-2

eBook ISBN: 978 178531-067-6

--

Ebook Conversion by www.eBookPartnership.com

Contents

Hide not your talent. They for use were made.

Whats a sundial in the shade?

Benjamin Franklin

Foreword by Tim Rice

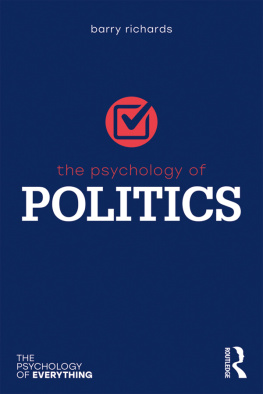

S OUTH Africas Barry Richards is simply one of the greatest batsmen cricket has ever seen, whose talents have at times been bracketed with those of Sir Donald Bradman, Sachin Tendulkar and his namesake Vivian. The comparison would have been made more often but for the well-known tragedy of his career: it coincided almost exactly with his countrys period of isolation from the cricket world, 1970-1991, as a result of apartheid. This meant that he only played four Test Matches, all against Australia, all of which were won by South Africa, and his contribution of 508 runs at an average of over 72 was a major factor in this triumph. After that magnificent success, the door slammed shut on South Africas international cricket and by the time it was prised open again, Barry had retired. He played first-class cricket until 1983, notably for Hampshire and South Australia, and nearly every time he went to the wicket, his admirers could not but wonder what might have been.

I have had the honour of knowing Barry as a friend for many years and have even played in a couple of extremely minor club matches which he graced with his presence. He was long gone from the first-class game but his first-class ability and modesty were still very much in evidence. He generously refrained from smashing me out of the attack and during one of my more testing spells (the ones when the ball occasionally hits the deck before getting to the batsman) even managed to give the odd spectator the impression he was not quite sure how to deal with me. Not true, obviously, but I am eternally grateful for the gesture.

I am delighted that Andrew Murtagh is herein paying tribute to this wonderful player, who has known great ups and downs in life, both off and on the pitch, but remains above all a sportsman and gentleman without bitterness and with few equals.

Preface

It was as if Yehudi Menuhin had called into the Festival Hall of a morning, taken his fiddle on stage and reeled off faultless, unaccompanied Bach all day just for the pleasure of the cleaners, box-office clerks, odd electricians or a carpenter who chanced to be there without central heating, of course without taking off his coat.

Tony Lewis on Barry Richardss innings at an empty Lords, 1974

I T just happened as it happened. No one had planned it, nothing had been scheduled, nothing organised. It was a day much like countless others in the life of a county cricketer. Net practice when no match is on the fixture list is not the way most professional cricketers would choose to spend a rare day off but the custom was almost de rigueur; it would be a brave captain who would say to his team, You deserve a rest, lads go and play golf.

And a captain who was brave enough to defy custom would only feel he could get away with it if his team were looking down on everyone else from the top of the championship. Sixteen other sides, of course, would be looking upwards, so naughty boy nets would be ordered and everyone had to be there.

And that included the stars, the overseas players. In the 1970s, every county was allowed two overseas players on its books and a brief glance at the playing staffs of those days would reveal a glittering collection of the worlds finest cricketers. Today, counties employ overseas players who are barely recognisable to the general public. Central contracts have put paid to county cricket being the finishing school for Test cricketers from other countries.

Even the England players now have little more than fleeting contact with their home county.

It was different then. The Hampshire side that gathered together at 10am by the nets at the county ground in Southampton one day in the 1974 season included two of the best cricketers on the planet Barry Richards and Andy Roberts. Actually, there was a third Gordon Greenidge but owing to an oddity of the rules, he was registered as an Englishman, even though he had nailed his colours firmly to the West Indian mast.

He had come to this country from Barbados when he was 14 and was developing into one of the worlds most powerful and destructive opening bats. England, West Indies, Reading, Marswe didnt care where he came from as long as he was in our side. I say our side because I was in that group of Hampshire players padding up or marking out their runs for the ensuing net practice. I was a fringe player, it has to be said, but though I was frustrated at my seeming inability to make much of an impact in the first team, I was nevertheless tickled pink to be rubbing shoulders with the best in the game.

For Hampshire were the best. The championship pennant fluttered proudly at the top of the flagpole and there was every hope, nay expectation, that the previous years triumph would be repeated.

Especially now that the worlds fastest bowler was registered to play for us. Those who had played with Roberts in the Second XI the season before, while he served his years period of qualification, were only too aware of his raw pace and his deadly potential. There had been one match, against Gloucestershire at Bournemouth that had already acquired legendary status and had done much to promote his fearsome reputation. Gloucestershire were 30-odd for one, with numbers six and seven at the wicket. The missing batsmen were either back in the pavilion nursing painful bruises or on their way to hospital. He was fast all right and that winter he had already made his Test debut for the West Indies.

The other overseas player was Barry Richards, who, by contrast, had no need to make a name for himself. Among the county fraternity, to say nothing of the wider cricketing public, he was regarded as the most technically proficient and naturally talented of any batsman on earth. Even so, together with one or two others in the Hampshire team that summers morning, he did not particularly relish the prospect of a morning in the nets; county cricket is a treadmill and he would rather have had the morning off, to relax and to catch up on his mail. But all were professionals and if nets had been ordered, then nets it must be. Everyone just got on with it.

Such practice sessions always followed a pattern, a routine. The batsmen would go in first, usually in the same order as on matchdays. There would be ten minutes in one net where the seamers were operating and then the coach would shout out, Change nets! and a further ten minutes would be spent in the spinners net, where the surface was a little bit worn. By the time it came for the bowlers to bat and the batsmen to bowl, everybody had had enough and things rapidly deteriorated. How do you expect me to hold my end up if the rest of you wont bowl to me? would be the constant lament of the tail-enders to the retreating backs of his team-mates as they made their way back to the dressing room and a reviving cup of tea.

Next page